Disruptive Thoughts

Image Source: Pixabay

Physicists have a concept called “entropy,” which basically says systems will tend to move from orderly to disorderly over time. Entropy is central to physics, thermodynamics, and other fields of physical science.

Economics, however, isn’t a physical science. The way we allocate scarce resources isn’t bound by fixed laws of the universe. We have some general principles that are mostly reliable, but not always and everywhere. The rules can change. I described last week one way in which they have. (For some reason, that letter provoked a lot of responses, voicing both approval and disapproval. I read every reply that I see. Thank you for sending them.)

At its best, economics delivers the opposite of entropy, harnessing chaos into orderly systems that create opportunities and raise living standards for everyone. Yet a type of entropy still seems to apply, because these systems eventually change. Without careful monitoring, they can become dead weight bureaucratic cash sinks.

There’s small change and big change. The small ones are notable: recessions, market crashes, etc. You’ll see several in your lifetime. The greater changes tend to be technology-driven: the Industrial Revolution, the internet, and now maybe artificial intelligence, robotics, and what I’ve called the Age of Transformation.

When you are living through such change, it’s easy to get caught up in the moment. Change is hard. But it’s also inevitable, whether we like it or not. The good news: Most people will not only muddle through, but their lives will improve and the lives of the children will be even better. That’s what free market entrepreneurialism delivers.

Sometimes, however, life changes and some changes are hard. There’s no sugar-coating that. Likewise, the changes will be harder on some people than others. There’s no sugar-coating that, either. We just have to prepare as best we can.

Today I’ll tell you about a time in the past when people faced a challenge similar in some ways to our own. Then we’ll talk about the differences.

Resistance Was Futile

Today we use the word “Luddite” to describe those who fear new inventions, fighting to avoid change however they can. But the Luddites were actual people in 19th-century England. And if you or I had faced what they did, we might not have liked it, either.

Here’s a short description from History.com.

“The original Luddites were British weavers and textile workers who objected to the increased use of mechanized looms and knitting frames. Most were trained artisans who had spent years learning their craft, and they feared that unskilled machine operators were robbing them of their livelihood. When the economic pressures of the Napoleonic Wars made the cheap competition of early textile factories particularly threatening to the artisans, a few desperate weavers began breaking into factories and smashing textile machines. They called themselves ‘Luddites’ after Ned Ludd, a young apprentice who was rumored to have wrecked a textile apparatus in 1779.

“There’s no evidence Ludd actually existed—like Robin Hood, he was said to reside in Sherwood Forest—but he eventually became the mythical leader of the movement. The protestors claimed to be following orders from ‘General Ludd,’ and they even issued manifestos and threatening letters under his name.

“The first major instances of machine breaking took place in 1811 in Nottingham, and the practice soon spread across the English countryside. Machine-breaking Luddites attacked and burned factories, and in some cases, they even exchanged gunfire with company guards and soldiers. The workers hoped their raids would deter employers from installing expensive machinery, but the British government instead moved to quash the uprisings by making machine breaking punishable by death.

“The unrest finally reached its peak in April 1812, when a few Luddites were gunned down during an attack on a mill near Huddersfield. The army had deployed several thousand troops to round up these dissidents in the days that followed, and dozens were hanged or transported to Australia. By 1813, the Luddite resistance had all but vanished. It wasn’t until the 20th century that their name reentered the popular lexicon as a synonym for ‘technophobe.’”

I suspect the original Luddites didn’t fear technology so much as they feared losing their livelihoods. At the time, weavers were skilled craftsmen, often operating their own shops with a few apprentices. They were part of that era’s middle class, occupying a space below the aristocracy but above farm laborers. The idea of slipping down the ladder must have terrified them (not unlike today’s “knowledge workers” who do things AI is rapidly learning to do without human help).

Economic reality left few alternatives, though. The new technology was staggeringly more productive. According to one source I found, mechanized cotton spinning increased per-worker output around 500 times. The cotton gin removed seeds from cotton about 50 times faster than a human could. These weren’t small differences. They were revolutionary to the same degree AI is revolutionary when it produces in a few seconds a legal document (to name just one example) that would have taken a human attorney days to produce.

Gradual or Sudden

I imagine the weavers back then pointed to the machinery’s flaws and mistakes. “See, we can do it better!” That was probably true but also irrelevant. At some point, higher productivity outweighs lower quality. Machine quality improves, though, eventually surpassing even the best human experts. This gives everyone access to get better products at lower prices.

Two things happen during these periods of revolutionary technological change:

- Higher productivity leads to innovation that makes life better and

- Those same productivity gains cost some people their jobs or income.

These two changes—one good, one bad—happen at the same time. But in any given household, one of them predominates. Those rendered jobless don’t get to enjoy the fruits of innovation. Meanwhile, those who become more productive may forget the other group’s misery. Not surprisingly, conflict often follows.

The Luddite violence occurred in the early 1800s, a period we now call the First Industrial Revolution. The innovations it launched would enhance everyday life for everyone. But it was the Second Industrial Revolution, beginning around 1890 and extending into the Roaring 1920s, before the new technologies reached most people. In between was a long period of adaptation.

The adaptation period, while often uncomfortable, allowed enormous change to unfold gradually. Some groups like the Luddites saw their lives upended quickly but others had time to adjust. They were able to learn new skills, relocate to places with more opportunity, and otherwise find a way forward in a different kind of economy. We went from an agrarian economy where 90% of the people worked producing or moving food in Colonial America. By 1860 it was 53%, down to 23% in 1940, and less than 2% today. By the way, that 2% today represents more than 2 million farms. The growth in agricultural productivity is utterly astounding. Labor use is down by 80% or more. You can read about it here.

Note that this massive shift happened over almost 10 generations. People had a lot of time to adapt their economic circumstances even though it was always individually challenging. Electricity was a huge change but took multiple decades to show its true impact. Ditto for trains and then the automobile.

Today’s workers may not have that luxury. A faster pace of technological change means many kinds of jobs are being replaced faster than the economy can provide new ones for the displaced. And this time, young workers and those with fewer skills are bearing the brunt of the change.

In writing this letter, I did some browsing on jobseeker bulletin boards. I saw many examples of experienced technology workers in their 40s and 50s (and a few in their early 60s) who had been laid off, presumably because new technology had outmoded them. While they wanted to find new roles, few seemed desperate. Many even talked about the large portfolios they had accumulated in their apparently well-paid careers. Some owned their homes mortgage-free.

Most were prepared to wait and, if necessary, just retire early.

In contrast, AI is wreaking havoc on job prospects for young workers, particularly recent college graduates. They prepared for a world in which companies hired large numbers of young professionals to do the “grunt” work of programming, analyzing numbers, writing reports, etc.

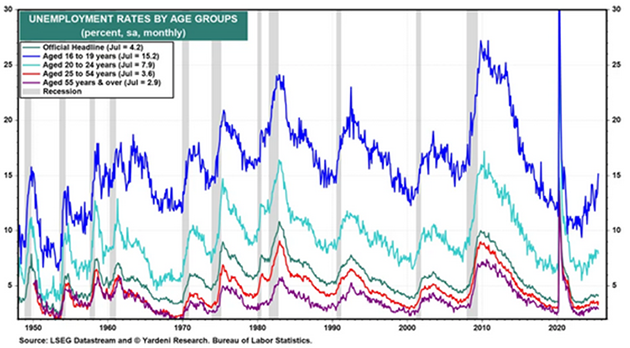

Those jobs still exist, but AI tools mean there are far fewer of them than even 2–3 years ago. This is one reason unemployment is far worse for younger cohorts. Here’s an Ed Yardeni chart I shared last month.

Source: Yardeni Research

While higher unemployment for young workers isn’t new, it is unusual to see it rising so much faster than in the 25–54 and 55+ cohorts. This strikes me as an important difference from the Luddite example. Back then, the middle-aged craftsmen had the most to lose. They had invested a lifetime in mastering skills the new technology threatened to kill. Today, many older workers (though certainly not all) are better positioned to endure disruption than the young ones. And ironically, the younger ones are far more likely to embrace the technology that is taking their jobs.

Historically, having a large population of economically distressed young adults, especially young males, isn’t great for social stability. It would help if more could be attracted into the kind of work AI hasn’t yet reached–the construction trades, for example. But those who invested years in earning a college degree—and may have large student loan debts—are naturally hoping to find a job in the field they prepared for.

As noted, the real key is timing. Will AI unlock new kinds of growth that create enough jobs to absorb those it displaces? I feel sure it will, but I don’t know how soon.

Asymmetric Gains

Last week Dave Rosenberg published a piece I need to think about and perhaps write about in a future letter. Briefly, he thinks the business cycle of expansions and recessions is no longer delivering useful investment signals. Structural “mega-forces” are reshaping markets in ways cycles alone can’t explain. He then lists several such forces, the first being AI. Here’s Rosie:

“Today’s breakthroughs have so far been narrower and clustered. Semiconductors, hyperscale cloud capacity, and applied AI models absorb the bulk of capital flows, while most industries remain only marginally affected. The result is highly concentrated productivity and profitability—a widening divergence between firms able to harness AI at scale and those left behind.

“Early adoption has created exponential gains for chipmakers, hyperscalers, and software leaders. Retail, Hospitality, Health Care, and other service-heavy sectors have lagged substantially. AI looks less like a rising tide than a powerful wave lifting a few boats. Yet, diffusion is inevitable: logistics optimization, medical imaging, algorithmic lending, and personalized education. The eventual scope will be broad, as it has been with every general-purpose technology, but the path there is jagged and contested.

“The macroeconomic effects are profound. Automation dampens labor market cycles by reducing the elasticity of headcount to demand swings. Firms that deploy AI in coding, call centers, or logistics need fewer workers during downturns and can scale without proportionate hiring in upswings. This suppresses wage-driven inflation and makes employment less reliable as a growth signal. At the same time, productivity gains accrue asymmetrically, reinforcing the gap between winners and laggards.”

To summarize that last paragraph: Technology-driven productivity enhancement is separating employment growth from economic growth. That’s true at both the macro level and for individual companies.

In the long run, this is probably good. Population growth is slowing and will turn negative soon (absent more immigration). We need higher productivity to maintain economic momentum. But again, it’s not enough to have a job for every worker. They have to be the kinds of jobs those workers can do, located in places the workers want to (and can afford to) live.

AI is only one of many significant disruptions ahead. Ultimately, almost all will be positive for mankind. In the short run it will be individually disruptive, as it was for early 1800s textile workers. Robotics really will take jobs in a wide variety of fields. And not just at work.

Housework, caring for the elderly, healthcare, agriculture, and more. All those jobs are at risk. But affordable robots will also give entrepreneurs the opportunity to create whole new businesses, serving the public with better products at lower costs. And those new businesses will need human employees. Similarly autonomous vehicles will take jobs, but the increased productivity and dramatic drop in fatal accidents will ensure that it happens.

The next 10 years will see astounding gains in healthcare. We are on the cusp of extending health span significantly, with increased lifespan following shortly. All these technologies and more are going to happen in less than a generation. It will be a disruption we have never encountered in terms of the speed of different technologies reaching ubiquity.

This will happen as a witch’s brew of politicians promise to “protect” various jobs and industries. There will be calls to have the government “do something.” There is a role for government, but in helping people transition to a new future, not protecting old jobs.

This is all going to happen at the same time as we have geopolitical crises, sovereign debt problems, and the social crisis stemming from generational leadership changing (Neil Howe’s The Fourth Turning). Clashes caused by the over-production of elites vying for power (Peter Turchin’s End Times), and young people not trained for the future we will actually experience will all come together in the latter part of this decade.

Buckle up. We all need to figure out how to be part of the solution.

More By This Author:

The Rules Have ChangedHousing Headaches And More

A Philosophy Of Investing

I Need Your Help

Among AI’s many effects is the way we work at Mauldin Economics. We are using AI systems internally in various projects, mainly on an experimental basis. But because ...

more