Did Central Banks Arrive At Their Target Inflation Rate By Mere Fluke?

Have you ever questioned why central banks around the world target CPI inflation at 2%?

One might think it would be complicated to explain the lengthy calculations, econometric-based research, and late-night debates that went on in order to come to this figure, but no.

Sadly the answer is someone licked their finger, stuck it in the air, and did what felt ‘right’.

Or, more specifically, we got to a 2% inflation target because the central bank of New Zealand did it and inflation came down so everyone jumped on the bandwagon.

After the high inflation of the 1970-the 80s and the high interest rates and recessions that came with the reduction of inflation, central banks around the globe started asking themselves ‘what should the rate of inflation be?’.

Formal Inflation Targeting

Some central bankers maintained that inflation should be zero.

After all, inflation is a decline in purchasing power of the very currency central banks print, but others argued that some inflation is healthy and warranted and gives central bank flexibility.

New Zealand passed the Reserve Bank Act of 1989 which aimed to grant the central bank political independence from the whims of politicians.

However, as part of the Bank Act, the central bank had to set a formal inflation level. If the inflation level was not respected then the head of the central bank could be dismissed.

The story goes that to counter existing public perception central bankers would be content with high inflation.

The finance minister said in an interview that the central bank was aiming for inflation of around zero to 1%.

This was later expanded to give the central bank more room for error and the inflation target of zero to two percent was implemented.

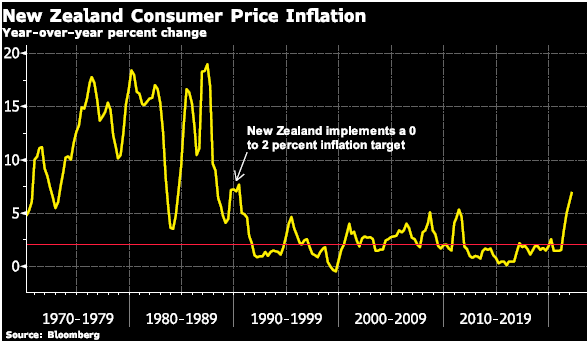

When the central bank of New Zealand implemented the target at the end of 1989 inflation was 7.6%. Also, by the end of 1991 consumer price inflation was 2%!

New Zealand Consumer Price Inflation Chart

The more central banks that adopted the inflation target the more the discussion about the ‘actual number’ became a topic of analytical and academic papers.

Many thought that a zero-inflation target should be the goal.

The reasoning a pound (or dollar) today should have the same purchasing power as a dollar a decade from now or even two or three decades from now.

Purchasing power erosion of fiat currency is a topic that gold and silver investors are acutely aware of and below is an example of a quick calculation for measuring that erosion.

The rule of 72

This rule of 72 is a ‘rule of thumb’ to map out the effect of compounding. To use the rule divide 72 by the rate of compounding you wish to understand.

Let’s use 2 as an example. So, assuming 2% inflation we divide 72 by 2 and get 36. This means at 2% inflation the price of an item would double every 36 years.

Moreover, using the current UK CPI increase of 9% for April 2022 the price of an item would double in 8 years.

Said another way if consumer price inflation increases at the rate of 9% for the next 8 years, then a pound would only purchase half as many goods and services in 8 years as it does today.

With essential commodities such as wheat price increases of more than 20% – 72/20 is 3.6 years to double in price.

However, the rule of 72 can be used to the advantage of silver and gold investors.

If inflation is expected to continue at the rate of 9% then the price of gold and silver should also rise at least 9%, which means that the price of gold and silver will double in 8 years.

If investors expect that the rate of inflation is going to climb even higher say at 10% then gold and silver prices would double in 7.2 years.

As the rule of 72 shows that any inflation rate above zero means all fiat currencies’ purchasing power erodes. Shouldn’t central banks care about that fact?

Well, even former Federal Reserve Chairs Paul Volcker and Alan Greenspan both, argued that inflation should not be a factor in business decisions, or that it should be essentially zero.

But others argued that this could be ‘dangerous’ and at the forefront of this argument was non-other than the current US Treasury secretary Janet Yellen (and Fed Chair from 2014-2018).

In the mid-1990s Yellen made the argument that having a zero-inflation target ‘could paralyze the economy’ she noted that this could particularly be a problem during recessions.

Dr. Yellen is noted as saying

“To my mind, the most important argument for some low inflation rate is the ‘greasing-the-wheels argument’”.

Yellen’s argument was that inflation offers a cushion for employers in a downturn because during a downturn employers can hold employees’ pay steady.

Also, if there is inflation then the wages the employer pays in inflation-adjusted terms decline.

In other words, if a worker makes $20 per hour and inflation is rising 2% per year and the price of the goods the worker makes increases the 2% per year then it costs the employer less per item to keep that worker employed.

And some economists and officials are calling for higher inflation targets for central banks – say 3% to 4% to give central banks even more maneuverability.

Our guess is those calling for higher inflation targets aren’t the worker in the above example making $20 an hour while the price the company charges for the good increases.

But, instead, the ones who are tasked with making the country’s debt levels look ‘less’ apocalyptical.

Bottom line is that the 2% inflation target was born out of somewhat of a fluke.

There is not a great reason for this target besides it was what worked coming out of an era of much higher inflation.

Of course, that era was a whole different ball game to the one we have now.

But the sentiment of central bankers remains the same; to keep the jig up, they’ll do whatever it takes.

In short, they’re more than happy to use inflation to reduce their massive debt levels, destroying the value of our money in the process.

Disclosure: The information in this document has been obtained from sources, which we believe to be reliable. We cannot guarantee its accuracy or completeness. It does not constitute a solicitation ...

more