De-Risking Is A Two-Way Street

Turns out, the feeling is mutual.

Over the past couple of months, we’ve been talking about US efforts to fortify supply chains by reducing reliance on China. The US government is funneling over $900 billion toward reshoring through the CHIPS Act, the Inflation Reduction Act, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, and tariffs on Chinese goods.

We’ve heard from our friends Louis Gave and Jacob Shapiro about US efforts to decouple or de-risk away from China. I’ve also shared a special video from the Macro Team about the opportunities this is creating for investors.

There’s another side to this story, though, which most US-centric investors never consider: China is trying to do the same thing. China wants to de-risk its economy away from the US and US allies.

As my guest George Magnus puts it in today’s Global Macro Update interview, China has been “pursuing policies that we would now call decoupling” for the past 10 or 15 years. Its goal is to “establish dominant market shares of 70% or more in a range of modern industries at the frontier of science and technology.”

George Magnus is the former chief economist at UBS. He’s also the author of several books, including Red Flags: How Xi’s China Is in Jeopardy, and is an associate at Oxford University’s China Centre. You can find his latest thoughts at georgemagnus.com.

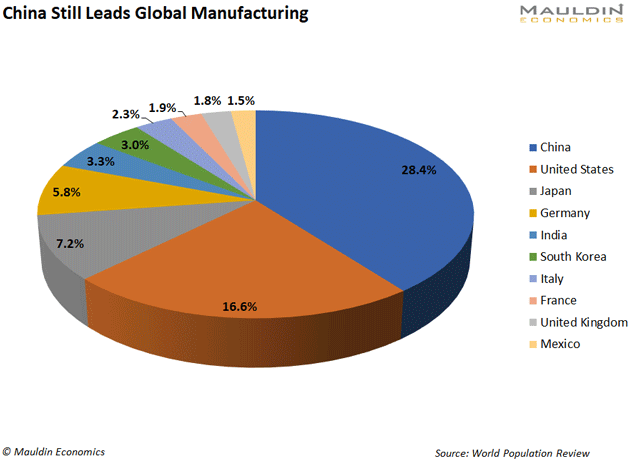

In the interview, George says that de-risking is an ongoing process for the US, and it will never be absolute. China is still the world’s #1 manufacturer, making 28.4% of the world’s goods. You can see this in the chart below.

Neither the US nor Chinese governments are particularly concerned about where lower value items like textiles are produced. Instead, de-risking is about fortifying supply chains for goods with national security value.

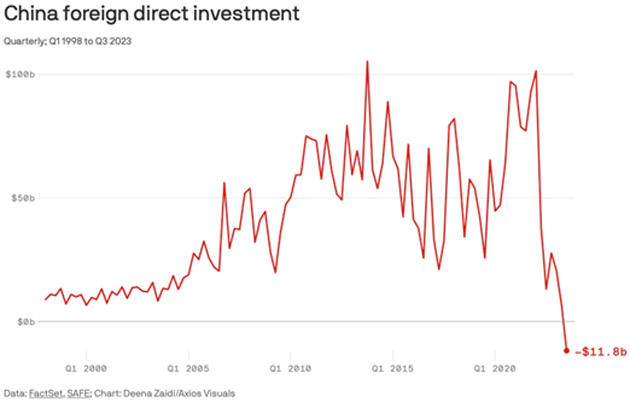

George and I also discuss how China pays lip service to welcoming foreign companies. But at the same time, it fosters a business environment that is increasingly hostile to foreigners. This is showing up in the numbers. In the third quarter of 2023, foreign direct investment in China went negative for the first time since 1998 (which is as far back as the data goes).

Source: Axios

We also discuss a fundamental change flying under the radar of most US investors: The People’s Bank of China, which is China’s central bank, no longer enjoys the slightest pretense of independence. It’s now under the direct control of China’s Central Financial Commission. For perspective, George says this is roughly the equivalent of the controlling party in Congress managing Federal Reserve policy. As I said to George, “What could go wrong?”

More By This Author:

What Could Go Wrong? - Saturday, Nov. 11My Affinity For Short-Term Interest Rates

Debt Scores