Climate Vs Incomes

If a single chart can illustrate the challenges in reducing emissions, it’s the scatterplot below showing per capita energy use and GDP. Raising living standards requires more energy. The relationship between these two variables is hard to break. Richer countries consume more energy, and becoming richer requires more energy. Everyone wants to move up and to the right. They want to live more like Americans.

This is the fundamental challenge to moving the world off fossil fuels. Reducing emissions means paying more for energy as well as using less of it, which is completely at odds with the desire in developing countries to develop.

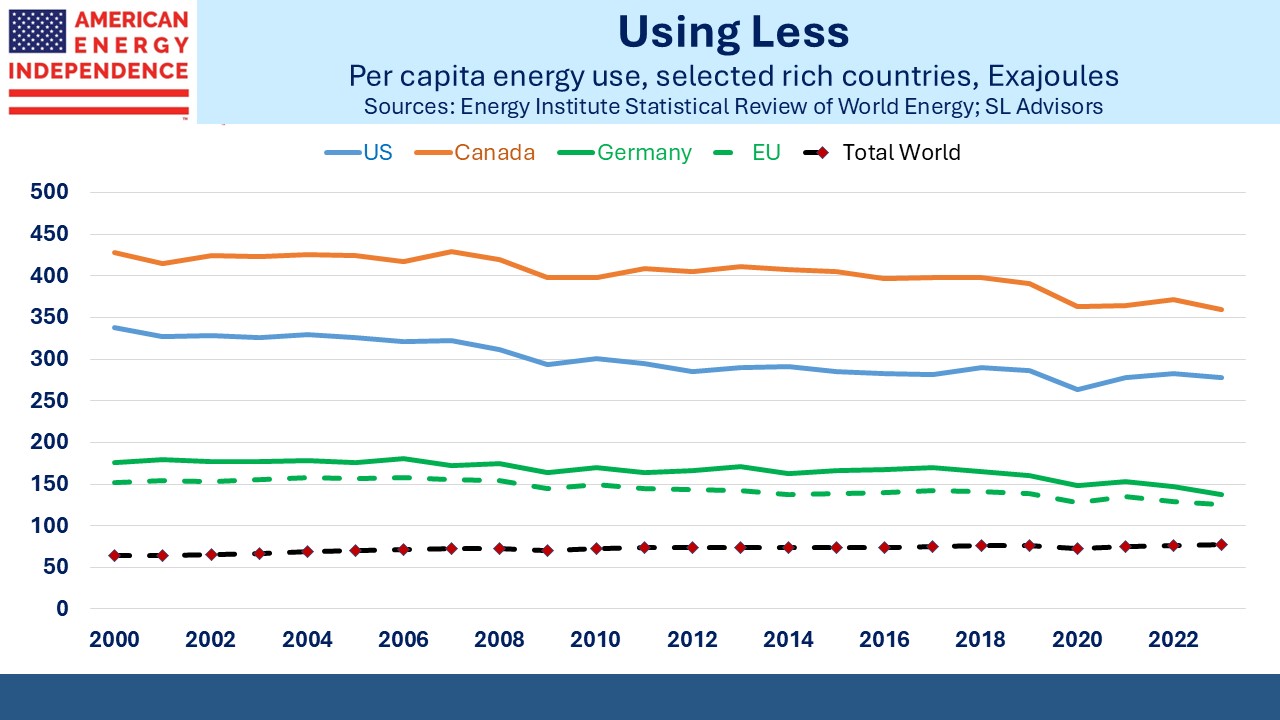

Per capita energy use varies enormously. Americans consume over 3X the global average. It’s not a perfect measure – China’s per capita energy consumption is close to the EU average even though incomes are less than half, which reflects the larger share of energy-intensive manufacturing in their economy as well as relatively low energy efficiency.

Canadians will be surprised to see what energy hogs they are. It’s not just their mix of economic activities. As my family in Ontario knows well, winter is long and cold north of the border, which pushes up energy consumption.

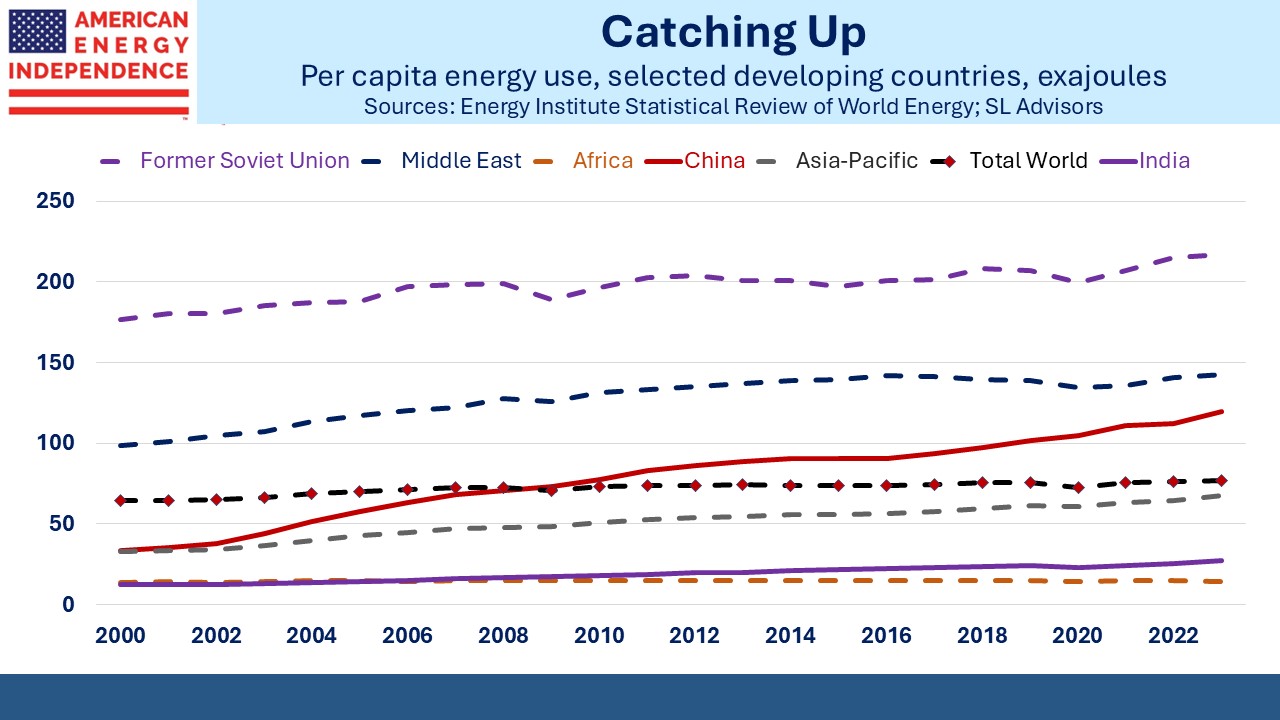

Getting richer means using more energy, and a substantial portion of the world’s population uses comparatively little. Moreover, concern about global warming tends to be greatest among rich countries, who are ironically better able to invest in mitigation against flooding or heatwaves.

An extended period of high temperatures in Pakistan was blamed on global warming, although for any specific weather event it’s impossible to know (see Energy By The Numbers). While scientists will point to the imperative to reduce emissions, Pakistanis will understandably favor more air conditioning, which means raising incomes and using more energy.

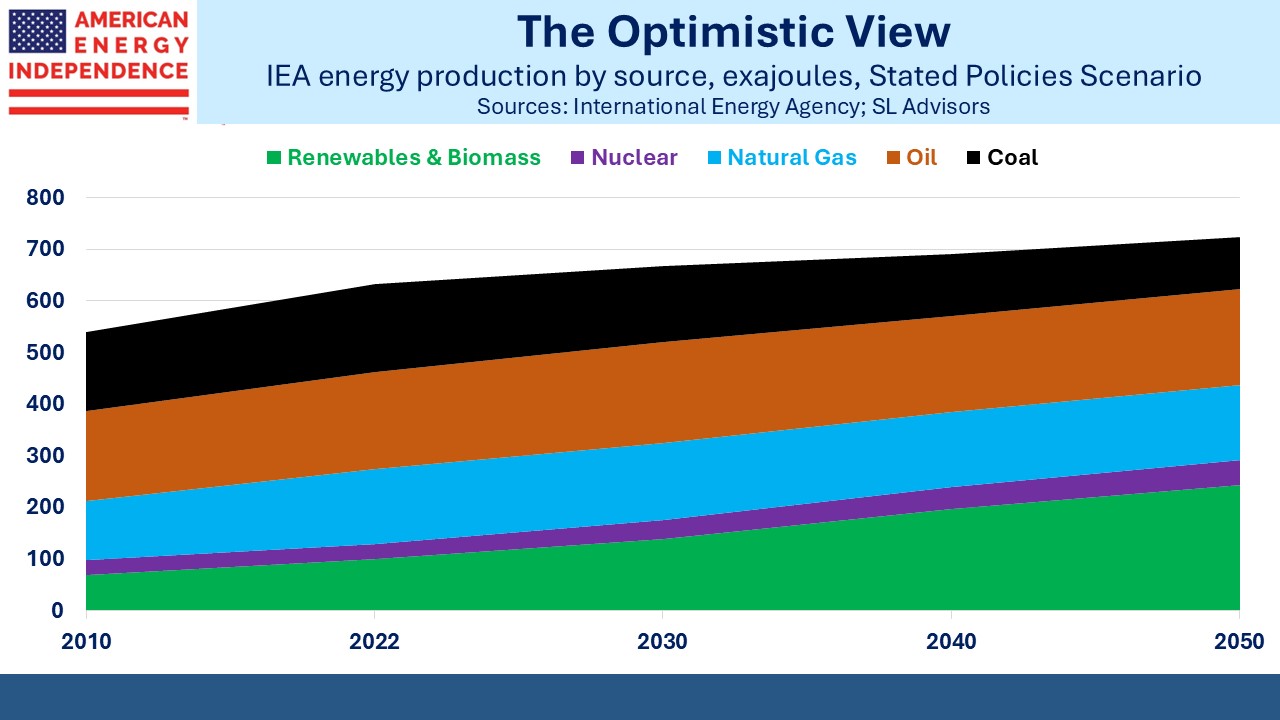

The International Energy Agency (IEA) publishes forecasts that are more aspirational nowadays, having dropped their original mission to provide unbiased analysis of energy markets. In their 2023 World Energy Outlook their Stated Policies Scenario, which is the closest to reality, projects 30 GigaTonnes (GTs, billions of metric tonnes) of CO2 emissions in 2050, down modestly from today’s 36 GTs. Even that includes heroic assumptions about declining coal use and sharply higher renewables.

The IEA calculates that if all the announced pledges on energy were implemented (their Stated Pledges Scenario), 2050 emissions would drop by two thirds to 12 GTs.

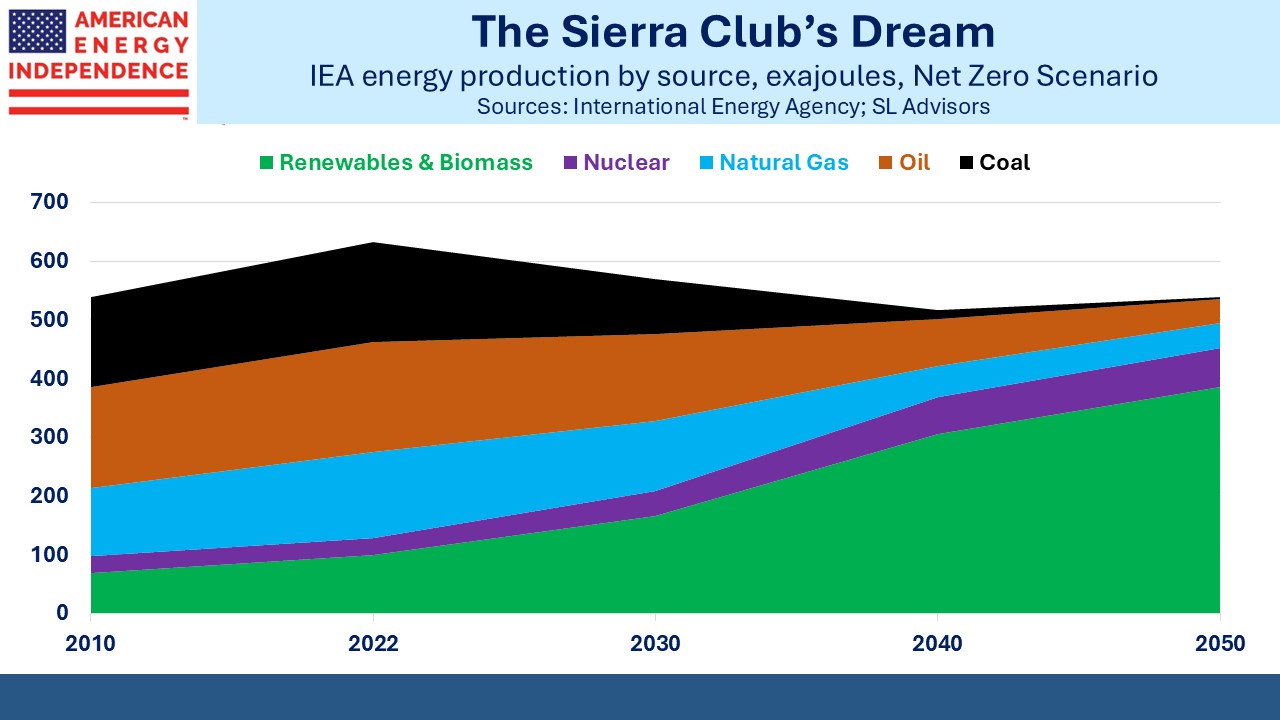

Their Net Zero Scenario shows just how implausible it is to eliminate emissions over the next twenty-six years. It includes an almost complete phaseout of coal by 2050, and an almost two thirds drop in natural gas consumption. It also assumes that total energy consumption is 15% lower by 2050 even though the world’s population is projected to be 9.7 billion by then (versus around 8 billion today).

Net Zero assumes nuclear power output would double. As fanciful as this scenario is, it wouldn’t be sufficient for the Sierra Club who wants the world to stop using nuclear as well.

The only way to square the circle is for rich countries who care the most about climate change to make enormous transfer payments (think $TNs annually) to poorer countries, to compensate for high-cost renewable energy. Climate extremists will counter that solar and wind are cheaper, but the contrary evidence is overwhelming. Germany has among the most expensive electricity in the world thanks to their big push into renewables (see Germany’s Costly Climate Leadership).

US electricity prices for households rose 6.2% last year as renewables gained market share (see Long Term Energy Investors Are Happy). This lowered the system’s overall capacity utilization. Solar and wind operate around 20-35% of the time. Their increased reliance means more back-up for when it’s not sunny or windy – typically large-scale batteries or more natural gas. The cost of solar and wind isn’t just the cost of using them to provide power. You have to include the back-up too.

Rich countries are not going to make the necessary transfer payments, which would be on a different scale than the current subsidies and tax breaks directed towards clean energy. Energy prices are politically sensitive – the Biden administration has been acutely sensitive to the oil market, even though allowing higher prices would boost the appeal of the alternatives.

The inherent conflict between raising billions of people out of poverty and reducing CO2 emissions is going to favor the former. As developing countries get richer, they’ll begin to share the climate concerns of western countries. There’s not much evidence that they do today. So we’ll use more natural gas along with every other source of fuel. The upside case is that policymakers make a serious effort to persuade China, India and others to use more natural gas and less coal.

US natural gas infrastructure looks like a good long term bet to us.

We have three have funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Energy Mutual Fund: Catalyst Energy Infrastructure Fund (MLXIX)

Energy ETF: The Pacer Custom ETF Series (USAI)

Real Assets Fund: Rational Real Assets Fund (IGOAX)

More By This Author:

Oneok’s Deal Makes Everyone Happy

We Need Much Cheaper EVs

Cheniere Keeps Returning Cash

Disclosure: The information provided is for informational purposes only and investors should determine for themselves whether a particular service, security or product is suitable for their ...

more