A Tale Of Two Recessions: One Excellent, One Tumultuous

Some recessions are brief, necessary cleansings in which extremes of leverage and speculation are unwound via painful defaults, reductions of risk and bear markets.

Some are reactions to exogenous shocks such as war or pandemic. The uncertainty triggers a mass reduction of risk which recedes once the worst is known and priced in.

Far less frequently, structural recessions are lengthy, tumultuous upheavals that can set the stage for excellent long-term expansion or unraveling and collapse. In these structural recessions, 10% to 20% of the workforce loses their jobs as entire sectors are obsoleted and jobs that depend on excesses of debt and speculation go away.

In the U.S. economy of today, this would translate into a minimum of 14 million jobs vanishing, never to return in their previous form and compensation.

The old jobs don't come back and new jobs demand different enterprises, training and skills. Unemployment remains elevated, spending is weak and productivity is low for years as enterprises and workers have to adjust to radically different conditions. If the economy and society persevere through this transition, the stage is set for the reworked economy to enjoy an era of renewed prosperity and opportunity.

If an economy and society can't complete this transition, stagnation decays into collapse.

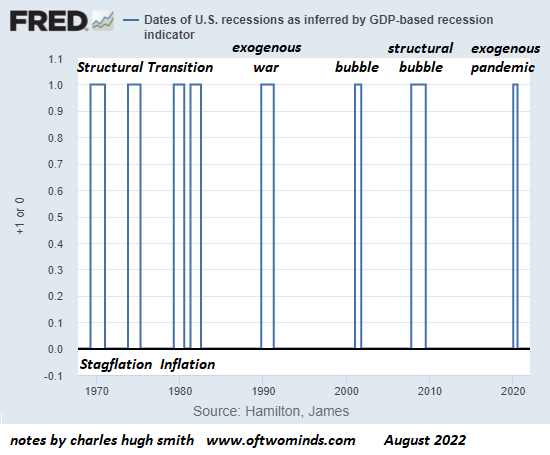

I've annotated a St. Louis Federal Reserve chart of U.S. recessions since 1970 to show the taxonomy described above. The stagflationary 1970s / early 1980s were a lengthy, tumultuous structural upheaval; the 1990-91 recession was triggered by the First Gulf War; the Dot-Com Bust in 2000-2002 was largely the unwinding of speculative excesses in the technology sectors (similar to the radio-technology bubble of the 1920s); the Global Financial Meltdown (aka the Global Financial Crisis) was the structural reckoning of unregulated global financialization excesses, and the 2020 recession was the result of policy responses to the Covid pandemic.

Each of these resulted in a multi-quarter decline in GDP, the classic (though flawed) definition of recession.

Recessions that cleanse the system of financial deadwood are necessary and yield excellent results. Per the Yellowstone Analogy ( The Yellowstone Analogy and The Crisis of Neoliberal Capitalism (May 18, 2009) and No Recession Ever Again? The Yellowstone Analogy (November 8, 2019), the deadwood of excessive speculation, leverage, fraud and debt issued to poor credit risks must be burned off lest the deadwood pile up and consume the entire forest in a conflagration of the sort that was narrowly averted in 2008-09 when fraud and risk-taking had reached systemically destructive extremes.

The problem with letting deadwood pile up so it threatens the entire forest is the policy reaction creates its own extremes. The coordinated central bank policies unleashed in 2008 and beyond established new and unhealthy expectations and norms, the equivalent of counting on central bank water tankers to fly over and extinguish every firestorm of excessive risk-taking and fraud.

Those emergency measures create their own deadwood, distortions and risk, and are not a replacement for prudent forest management, i.e. maintaining a transparent market where excessive risk is continually reduced to ashes in semi-controlled burns.

When systemic changes in the economy and society demand structural transitions, the resulting tumult can either creatively rework entire sectors, weeding out what no longer works in favor of new methods and processes, or those benefiting most from the old structure can thwart desperately needed evolution to protect their gravy trains.

If change is stifled as a threat, the entire economy enters a death-spiral to collapse. Some eras present an economy with a stark choice: adapt or die. Adaptation in inherently messy, as new approaches are tried in a trial-and-error fashion and improvements are costly as the learning curve is steep.

Sacrifices must be made to achieve greater goals. as I outlined yesterday in A Most Peculiar Recession, in the 1970s the U.S. economy was forced to adapt to three simultaneous structural changes:

1. The peak of U.S. oil production and the dramatic repricing of oil globally by newly empowered OPEC oil exporters.

2. The pressing need to reconfigure the vast U.S. industrial base to limit pollution and clean up decades of environmental damage and become more efficient in response to higher energy prices.

3. The national security / geopolitical need to encourage the first wave of Globalization in the 1960s and 1970s to support the mercantilist economies of America's European and Asian allies to counter Soviet influence.

Coincidentally, this last goal required the U.S. expand the exorbitant privilege of the U.S. dollar, the primary reserve currency by exporting dollars to fund overseas expansion of U.S. allies like Japan and Germany and running permanent trade deficits to benefit mercantilist allies.

These measures created their own distortions which led to the Plaza Accord in 1985 and other structural adjustments. Ultimately, the U.S. managed to adapt to a knowledge economy (Peter Drucker's phrase) and a more efficient means of production, resulting in a much cleaner environment and a leaner, more adaptable economy.

The deadwood of hyper-financialization and the distortions of hyper-globalization have now piled up so high that they threaten the entire global economy. Those who have feasted most freely on hyper-financialization and hyper-globalization must now pay the heavy price of adjusting to definancialization and deglobalization.

Those who have been living on expanding debt and soaring exports are in for a drawn-out, wrenching structural adjustment to the reversal of these trends and the fires sweeping through the deadwood that's piled up for the past two decades.

There will winners and losers in this global structural upheaval. Mercantilist economies that feasted on 60 years of export expansion will be losers because there is no domestic sector large enough to absorb their excess production, and those who feasted on the expansion of debt to inflate asset bubbles will find their reluctance to conduct controlled burns of their speculative debt-laden deadwood will exact a devastating price when their entire financial system burns down.

Those who didn't rely on exports for growth will find the transition much less traumatic, as will those who maintained a regulated, transparent market for credit that limited excesses of leverage and high-risk debt.

Those who adjust to structurally higher energy costs by becoming more efficient and limiting waste via Degrowth will prosper, all others will sag under the crushing weight of waste is growth Landfill Economies. I explain why this is so in my new book Global Crisis, National Renewal.

Recessions that are allowed to clear the deadwood and encourage adaptation yield excellent results. Those which don't lead to the entire forest burning down. Economies optimized for graft, corruption, opacity, and benefiting insiders will burn down, along with those that optimized speculative extremes of debt and those too rigid and rigged to allow any creative destruction of insiders' skims and scams.

Events may show that there are no winners, only survivors and those who failed to adapt and slid into the dustbin of history.

Chart courtesy of St. Louis Federal Reserve Database (FRED)

More By This Author:

A Most Peculiar Recession

Are Older Workers Propping Up The U.S. Economy?

China At The Crossroads

Disclosures: None.