David Beckworth On Fed Policy

David Beckworth has two interesting posts discussing how monetary policy is being impacted by a changing environment. He focuses on three issues: stablecoins, abundant reserves, and our unsustainable fiscal policy. In this post I’ll offer a few preliminary thoughts on these issues. In some cases, I don’t have enough expertise to have a high level of confidence in my views, so I’d welcome any feedback. Ideally, you’d show where I’m wrong, in which case I’ll “win” by becoming better informed on 21st century monetary policy.

In the first post, David suggests that dollar denominated stablecoins are likely to become an increasingly important part of the global economy:

Dollar-based stablecoins, with a market capitalization near $300 billion, were already projected to reach between $2 and $4 trillion in size by the end of the decade. The GENIUS Act and the prospect of skinny master accounts are likely to further accelerate this growth.

Should stablecoins become a dominant payment technology, the implications for the Federal Reserve could be significant. In this note, I focus on two key effects in particular: (1) the potential increase in the cost of the Fed’s balance sheet and (2) the potential expansion in its size.

Photo by CoinWire Japan on Unsplash

This could have a negative effect on Fed seignorage revenues:

One potential implication of the widespread adoption of dollar-based stablecoins is the displacement of physical currency. As digital dollars issued through stablecoins become more widely used, global demand for physical U.S. dollars will decline. This shift could prove costly for the Federal Reserve, which depends on its “currency franchise” to finance its balance sheet inexpensively.

Put differently, the Fed currently obtains zero-cost funding by issuing currency and investing the proceeds in Treasury securities that yield a positive interest rate. This spread is the Fed’s golden goose. But as digital dollars displace physical currency, that goose may be cooked—and the seigniorage will migrate from the Fed to the issuers of stablecoins.

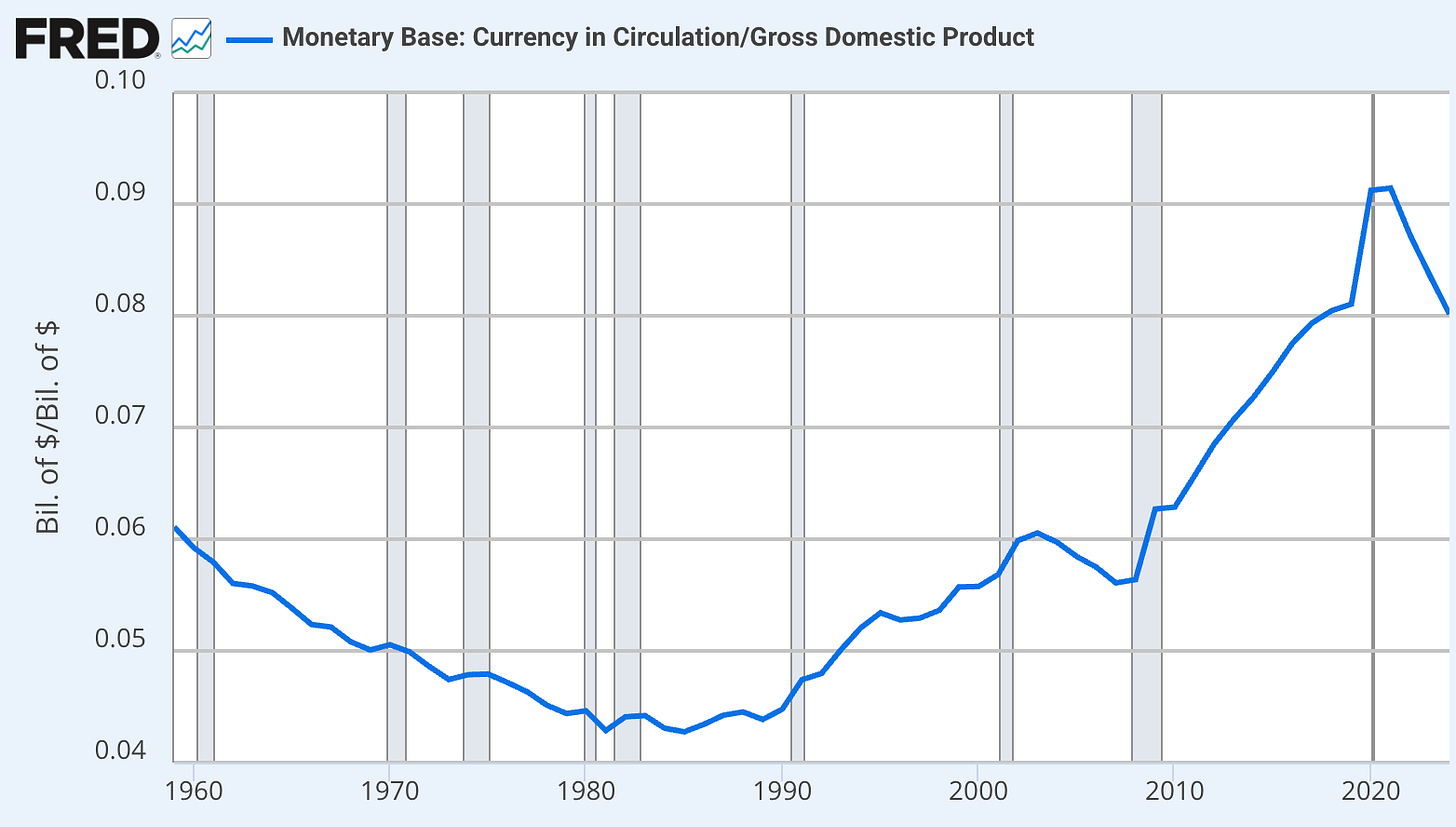

That seems like a plausible argument, but I’d need more information before forming an opinion. Consider that in recent decades there has been a dramatic decline in the use of currency in transactions. I hardly ever pay for goods in cash, and I don’t believe I’m atypical. And yet total currency demand has increased sharply since the 1980s, from just over 4 percent of GDP to roughly 8 percent.

You could argue that the trend reversed after Covid, but I’m skeptical. Currency demand is negatively related to nominal interest rates and thus grows very rapidly during low interest rate periods such as 2002, 2009-17 and 2020, while slowing or falling back during periods of rising interest rates, such as 2004-07, 2018-19 and 2022-24. The long run shift from cash to credit cards does not seem to have materially reduced the demand for cash, at least as a store of value.

The argument that stablecoins will displace currency largely hinges on whether this asset can displace the demand for cash as a store of value. The vast majority of the currency stock is composed of $100 bills that wear out very slowly, an indication that they are not being widely used in transactions, that is, as a medium of exchange.

In a sense, it is odd that currency is such an important store of value—its 0% return is dominated by other safe assets such as T-bills and FDIC-insured bank accounts. The most widely accepted explanation is that people value the anonymity of currency, which is quite useful for illegal transactions, but also for otherwise legal transactions where there is an attempt to evade taxes.

Unless the government were to essentially legalize money laundering, it is hard for me to see how stablecoins could displace the current high demand for US currency notes. Perhaps I’m missing something here. Will the government be able to prevent stablecoins from being used for money laundering? If the answer is no, then isn’t this the thing that we should be talking about? Wouldn’t that be more important than the hit to Fed income? Wouldn’t legalized money laundering lead to a sharp fall in income tax revenue?

David also argues that the replacement of currency with stablecoins would not lead to a smaller Fed balance sheet, that is, a smaller monetary base:

Consider first the case where people exchange cash for stablecoins backed by reserves, ON RRP balances, or Treasury securities. Suppose, for example, that I deposit $1,000 in cash at my bank, which returns the currency to the Fed. Currency in circulation falls by $1,000 while reserves rise by $1,000, leaving the size of the Fed’s balance sheet unchanged. I then use my new bank deposit to purchase a stablecoin, transferring reserves from my bank to the stablecoin’s bank—again, no change in total Fed assets or liabilities. Finally, the stablecoin issuer uses those reserves to purchase a Treasury bill in the secondary market, shifting reserves among banks but not altering the Fed’s overall balance sheet size. In short, the total size of the Fed’s balance sheet remains constant, but its composition shifts from currency to reserves.

I see a lot of possibilities here. If we were in the pre-2008 world with no interest on bank reserves, then a decline in currency demand would generally be accommodated by the Fed with open market sales. Rather than leading to another $1000 in excess reserves, the Fed would sell $1000 in securities to keep interest rates on target. (And even this assumption depends on why currency demand fell—recall the never reason from a price change problem.)

If we were in a world where stablecoins were backed one for one with deposits at the Fed, then the monetary base would not decline. But David is contemplating a scenario where stablecoin issuers are allowed to back stablecoins with Treasury bills, in which case it is not obvious to me that a $1000 decline in currency would lead to a $1000 increase in reserves. Perhaps, but given that the demand for bank reserves is highly elastic when IOR is set at the market interest rate, it seems like the Fed could choose a wide range of responses to a reduction in currency demand, just as IOR currently gives the Fed a fairly wide ability to adjust the size of the monetary base without dramatically affecting financial conditions.

Elsewhere, David presents a number of plausible scenarios where stablecoins lead to a larger Fed balance sheet, particularly where the coins are backed by “skinny master accounts” at the Fed:

Taken together, these three cases point in a clear direction: stablecoins generally raise the structural demand for Fed liabilities. When they replace currency, the effect is size-neutral for the Fed’s balance sheet even as the composition shifts from currency to reserves. When they replace bank deposits, the result is mostly neutral at first, but growing use of skinny master accounts could nudge reserves and the overall balance sheet higher. And when stablecoins create net new demand for dollar-denominated safe assets, particularly from foreign users seeking access to the U.S. payment system, the Fed’s balance sheet must expand to absorb that demand.

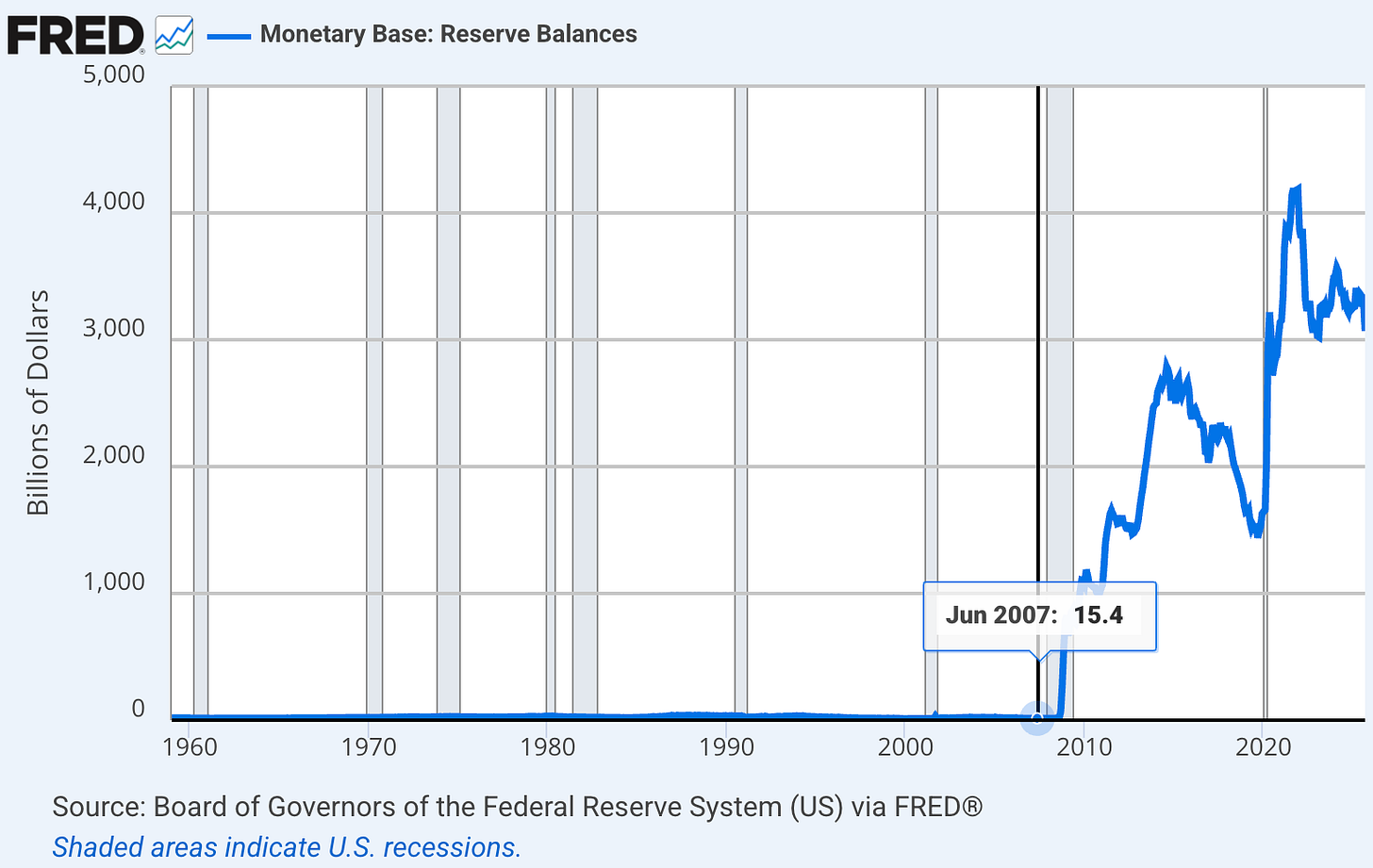

In my view, this all depends on whether we stick with the abundant reserves system or return to the pre-2008 system of scarce reserves (which both David and I prefer.) If the Fed does not pay interest on bank reserves, it is hard to see how deposits at the Fed could ever become an important component of the monetary base. Back in 2007, roughly 98% of the $840 billion monetary base was currency (mostly $100 bills) and less than 2% was deposits at the Fed:

If we stick with the policy of paying IOR and having abundant reserves, then the size of the Fed’s balance sheet depends on all sorts of factors, including decisions made by bank regulators.

In the follow-up post, David considers two possible scenarios:

If stablecoins mean greater demand for Fed liabilities, then what kind of balance sheet expansion might this entail? In my view, there are two ways for understanding this process. One view—rooted in the “safe asset shortage” narrative—sees the Fed’s balance sheet expanding to meet an excess demand for safe and liquid assets, with quantitative easing (QE) functioning as a kind of public intermediation service that supplies the safety that private markets cannot. The other view—anchored in concerns about fiscal dominance—sees the Fed’s balance sheet growing in response to an excess supply of safe assets, as mounting public debt pressures the central bank to absorb and manage an expanding stock of treasuries.

David presents both a cyclical and a structural explanation of the safe asset shortage. In my view, both of these explanations misdiagnose the zero bound problem that developed in late 2008. Rather than a lack of safe assets, I believe that a tight money policy drove NGDP growth from a trend rate of roughly 5% in the 1990s and early 2000s to negative 3% from mid-2008 to mid-2009. This collapse in NGDP growth sharply depressed the equilibrium interest rate, causing Treasury bond prices to rise as yields fell. The problem was not that fiscal policymakers were not running big enough budget deficits, rather that monetary policy was excessively contractionary.

[This view is certainly unconventional, and skeptical readers are directed to my book entitled The Money Illusion for a more complete explanation.]

David then provides some empirical evidence for the safe asset shortage model:

The U.S. experience fits within a broader global pattern. Across advanced economies from 2008 to 2019, the size of central bank balance sheets relative to GDP was negatively related to the average inflation rate. Countries with the lowest inflation—such as Switzerland and Japan—ended up with the largest balance sheets, while those with higher inflation, like New Zealand and Australia, required much smaller interventions. This pattern is precisely what the safe-asset-shortage view would predict: central banks expanded their balance sheets most aggressively where the demand for safe, liquid assets—and thus the disinflationary pressure—was greatest.

But this is also consistent with the model that I presented in The Money Illusion—that tight money led to falling NGDP, which led to lower nominal interest rates and a higher demand for base money. My critics often insist that QE is evidence that monetary policy was expansionary. Then why is QE negatively correlated with the inflation rate? This is clearly an example of the thermostat problem—central bank balance sheets are responding to macroeconomic conditions.

After examining the safe asset shortage hypothesis, David considered the opposite case—too many safe assets (i.e. too many Treasury securities) leading to fiscal dominance:

As the stock of Treasury securities balloons, the Fed faces growing pressure, explicit or implicit, to ensure that the market can absorb the supply without destabilizing yields.

We have been here before. Between 1942 and 1951, the Federal Reserve pegged Treasury yields across the curve to support wartime financing, standing ready to buy whatever amount of government debt was needed to keep short-term rates at ⅜ percent and long-term rates at 2.5 percent. This arrangement expanded the Fed’s balance sheet. It also subordinated monetary policy to fiscal needs until the 1951 Treasury–Fed Accord restored its independence. Arguably, a milder version of this dynamic resurfaced during 2021–2022, when pandemic-era borrowing surged and the Fed’s balance sheet ballooned in tandem. As George Hall and Thomas Sargent have documented in a series of papers, the Fed in this period looked less like it was leading policy than financing it.

This is a plausible argument, but I’m not entirely convinced. In 2021-22, the Fed seemed motivated by a flawed 1960s-style Phillips curve model—where easy money would somehow produce a healthy job market. By early 2022, the Fed realized that it had made a serious error and sharply raised nominal interest rates to restrain inflation. I see no evidence that the Fed was motivated by a desire to inflate away the debt.

The period of 1966-81 provides abundant evidence that a central bank cannot avoid “destabilizing yields” by using an easy money policy to monetize the debt. Indeed, nominal interest rates soared to over 15% toward the end of the Great Inflation of 1966-81.

Some have suggested we might adopt a milder form of fiscal dominance, say shifting the inflation target from 2% to 3%. But what does that accomplish? Yes, with the net national debt at roughly 100% of GDP an extra 1% inflation will reduce the real value of the national debt by 1% of GDP each year. But according to the Fisher effect, moving the inflation target from 2% to 3% will raise nominal interest rates by 1% in the long run, offsetting the ongoing gain from monetizing the debt. There would be a one-time gain from reducing the market value of the existing stock of Treasury debt, but given the unsustainability of current fiscal policy, that’s not going to produce any sort of permanent solution.

Lots of pundits seem to sort of wave their hands and suggest that since reducing the budget deficit is politically unpopular, we’ll be forced into fiscal dominance. But 1966-81 type inflation is probably 10 times more politically unpopular than reducing the budget deficit from the unsustainable 6% of GDP to a more sustainable 3% of GDP. Even the far smaller inflation of 2021-23 freaked out the public—just imagine their reaction to something like 1966-81!

I have no crystal ball here, and I would not rule out the possibility that we end up with fiscal dominance. We do seem to be exhibiting some banana republic tendencies. Rather, I’m trying to warn people that this wouldn’t be “taking the easy way out”, instead it would be vastly more unpopular than a combination of spending cuts and tax increases on the order of 3% of GDP. President Clinton and the GOP Congress did that sort of fiscal austerity in the 1990s, and I don’t recall that period as being one of highly unpopular macro policy.

David concludes by considering a sort of trilemma in contemporary macroeconomic policy:

Digital-dollar innovation, therefore, does not resolve the tension between dollar dominance, a small Fed, and financial stability—it intensifies it.

This tension suggests a trilemma. We can have a small Federal Reserve balance sheet and dollar dominance, but then we risk the kind of financial fragility seen in 2007–2008. We can have a small Fed and financial stability, but only by allowing the dollar’s global role to shrink and reducing the global demand for dollar assets. Or we can have dollar dominance and financial stability, but only by accepting a permanently larger Federal Reserve footprint. It appears, in other words, that the dollar’s global reach requires that the institution sustaining it must grow in proportion to its reach.

In my view there is a way out of this trilemma. We need to finally confront the fact that the profession erred in 2008. The Great Recession was not caused by financial fragility; the actual culprit was a tight money policy that drove NGDP sharply lower. We can have a small Fed balance sheet, dollar dominance, and financial stability. All it requires is getting rid of interest on bank reserves and adopting a policy of NGDP level targeting. Unless I’m mistaken, David also favors that sort of policy mix. So I am essentially arguing that David should be less pessimistic about his preferred policy regime.

PS. A superficial reading of the 1942-51 period might suggest that there is a painless way to do fiscal dominance. But on closer examination, the first five years of the policy (1942-47) led to a very high rate of inflation, peaking at 14.4% in 1947. After mid-1947, however, the Fed stopped pegging T-bill yields and inflation fell sharply. Between 1947 and 1951, the longer-term T-bond yields were often significantly below the 2.5% peg. From 1945 to 1951, the (adjusted) monetary base was roughly flat. The Fed was no longer achieving low nominal interest rates by rapidly expanding their balance sheet. When the 2.5% T-bond yield peg briefly threatened to lead to high inflation in 1951, the Fed abandoned the policy and quickly brought inflation back down.

More By This Author:

What Caused The Great British Inflation?What Should The Fed Have Done In 2008?

Right For The Wrong Reasons