Why Are People Now Selling Their Silver?

This week, the prices of the metals fell further, with gold -$18 and silver -$0.73.

On May 28, the price of silver hit its nadir, of $14.30. From the last three days of May through Sep 4, the price rose to $19.65. This was a gain of $5.35, or +37%. Congratulations to everyone who bought silver on May 28 and who sold it on Sep 4.

To those who believe gold and silver are money (as we do) the rising price of silver may seem right as rain. Why shouldn’t the dollar go down? It’s a rubbish currency, and any moment everyone else will realize it. And therefore it should go down in anticipation of that, right?

It certainly went down during this period, from 2.17 grams of silver to 1.61, or -26%.

What Is a Dollar Worth?

The question is: how much should it go down? This is a non-trivial question.

One cannot understand the value of the dollar in terms of its quantity (we have written so much material on this topic, it could probably fill a book). Nor with the assertion, often made in dark corners of the Internet, that the dollar is held up by faith, and as soon as the people discover it is backed by nothing then it will go to its intrinsic value of zero. In reality, the dollar is held up by the struggles of the debtors, who work overtime to produce goods and services to exchange for dollars.

The quantity of dollars is not a force pushing its value down. Any more than the quantity of gold pushes gold down. Money—and currency for that matter—has massive stocks to flows ratio. If it didn’t, it would not be the most marketable commodity—or credit.

The force pushing it down is the quality of new credit. As more and more credit is fed to zombie corporations (which the BIS defines as having profits < interest expense), as governments and individuals borrow more to consume—as more credit is counterfeit, that is taken without means or intent to repay—the quality of the currency declines.

It is natural for money—i.e. gold and silver—to bid less and less on a currency, the more and more questions there are about the quality of that currency.

But how much less? What should the dollar be worth on any given day? Everyone may have his own opinion, but of course, there is not a simple calculation that yields an undebatable number. This is one of the (many) flaws in that pseudo gold standard where the central bank attempts to fix the price of gold.

There is room for disagreement. One market participant may believe that the dollar should be worth 3g silver, another thinks 2g, and a third thinks less than 1 gram. Who is right? We don’t know—and neither do they.

This problem is exacerbated by the fact that people tend to extrapolate. If the price has been falling, they tend to assume it will—and should—continue to fall. And they factor this into their idea of what it’s worth.

So not only does each participant not agree with others on the right price, his own valuation today does not agree with his valuation from yesterday.

Price Is Set at the Margin

The market price reflects the interactions of all of these folks. It is set by participants at the margin. If some long-time holders sell one morning, then the price can move down. If that affects the value estimates of others and they sell, then the price can go down more.

The quality of the dollar may be falling steadily. Or it may be falling in bursts, with relative stability in between. The valuation judgments of the gold and silver market participants can get ahead of, or lag behind, the quality of the dollar at any given moment.

And they can trade based on momentum too. It is a common feature that when the price of something, e.g. silver, is rising, more traders pile on to what they see as easy money (i.e. dollars). So momentum is practically guaranteed to overextend a price move beyond the current valuation. Clearly, this happened in 2011. Silver hit nearly $50, which means the dollar fell to about 633 milligrams of silver.

The more the dollar is overextended to the downside, the more people begin to think it’s time to trade their money—i.e. metal—to bet on the dollar (yes, we do realize they don’t think of it in these terms). So a too-high price of silver begins to attract selling. At that point, there is a battle between the forces of momentum vs. rational valuation. But when momentum stalls, then the battle becomes lopsided. The price of the dollar could (and did) go far up indeed.

Some Speculators Hold

Now add one more factor to the mix. Many dollar-thinkers only buy gold and silver in the hopes of riding it to a higher price. They bet on money, only as a means to an end. They want more purchasing power. Some of them don’t like to sell at a great loss. They bought with great promises of silver to $200 and gold to $5,000. But the opposite happened. So they stubbornly held.

And now, years later, the price is rising. So they see it as their chance to get their dollars out, with less loss. They’ve seen price blips many times since 2011, and don’t trust that this blip will be any different from all the others (it actually is, see below).

Do these people assess that the dollar should be worth more than 1.6 grams silver? In effect, yes, that is their calculation. And more importantly, that is their effect in the market. They don’t think the dollar should—or more accurately, will—go down anymore so they buy dollars in anticipation the dollar will rise to 3g silver again. Or at least fear of holding silver while that move happens.

So there can be periods when the marginal market participants assesses the value of the dollar as 0.1g lower every day. And periods when they think it is rising 0.1g daily. There is no universal value that everyone can see. However, there are positive feedback loops and confirmation bias. There is momentum and therefore overshooting in both directions.

Volatility

For these reasons (and others), it is rare for a market to move in one direction monotonically. And when it does do so for a while, it can reverse sharply with a vengeance. This is why users of gold have to hedge their inventory (if they are not obtaining the metal from a Monetary Metals lease). The price risk often grows as the price is rising.

Expectations that the dollar should move to 150 milligrams of silver linearly and promptly (the inverse of the way most people would say it, $200 an ounce) are facile and naïve. Even if the dollar has by now fallen to such a low value (we don’t believe so), it would not be such a one-way move. And there is no reason for it to move there instantly.

Saudi Oil Bombed

We don’t normally comment on the news that occurred after the week’s close on Friday. But in this case, it is really big news. And also germane to this commentary.

Either the Yemen Houthi rebels—or Iran, depending on who you ask—bombed half of Saudi oil processing capacity on Saturday. As we write this Sunday evening (Arizona time), the price of West Texas Intermediate is up over +11%.

We are not geopolitical policy wonks, but this looks to us like a major event. Risk has just gone up, perhaps a lot. S&P futures are down about 0.65%. And the prices of gold and silver are up, +1.3% and +2% respectively.

Rising risk means a lower dollar. And we have to be clear what we mean here. Most people refuse to measure the dollar in terms of gold. Instead, they prefer to use either consumer goods (which are themselves measured in dollars)—so-called purchasing power. Or else they use the dollar derivatives such as euro and pound.

However, a crisis like this shows that the irredeemable dollar and its irredeemable derivatives are all in the same boat. If there is growing risk to trade and the global economy, then if the dollar is falling it will not be because the euro is rising. Or the franc. Or even the yuan.

The dollar will be falling against gold. And likely silver.

If this is so—it’s too early to tell if this drone strike on Saudi is just a flash in the pan—then we would expect the dollar to fall. Maybe it will get to 20mg gold and 1.2g gold. Given our frequent admonition to “be careful what you wish for”—we must reiterate that we don’t wish this to happen. But a sober assessment of geopolitics says it is distinctly possible.

In the meantime, we can say that the fundamentals of silver have moved up from mid-July and the mid $15’s to around $18 now. Remarkably, through these last two months, the scarcity of silver to the market (i.e. cobasis) has held pretty steady as the price has moved up. This is unlike the pattern set in many price blips in the past, particularly since August 7 and $17.

Was the attack on Saudi oil foreseen by market participants over a month ago? We doubt it (though we don’t know). But what seems clear is that the marginal market participant sees rising risks to be in the dollar, and is choosing to own metal. And at the current gold-silver ratio, the choice at the margin has been to hold silver.

In addition to the growing risks of the irredeemable currencies, there is the problem of negative interest rates. Savers may be disenfranchised—i.e. unable to affect the interest rate—but they can dump the paper altogether in exchange for gold and silver.

Zero Interest—Food or Poison

We have to add one last thing. President Trump this week called for zero or negative interest rates, going so far as to call the Fed “boneheaded” for so far not doing as he wishes they would. Even critics call it a “bold” move.

Whatever benefits Trump thinks to obtain from zero interest rates, including seemingly national prestige and of course stimulating the stock market, if not the economy, we should keep in mind the zero-interest vision of John Maynard Keynes. Keynes saw it as a way to “euthanize” the “rentier” (i.e. kill savers) and ultimately to overthrow the capitalist order.

So who is right? If the Fed drives yield to zero, does that help the economy, or does it destroy?

Like breaking a window, it may boost GDP. This is not a recommendation for breaking a window or the interest rate. It is a damning indictment of GDP as a measure of the economy, as it adds capital consumption.

Perhaps liberals and conservatives could agree that we should not have a central bank fixing the interest rate, under pressure from the president.

Let’s look at the only true picture of the supply and demand fundamentals below. But, first, here is the chart of the prices of gold and silver.

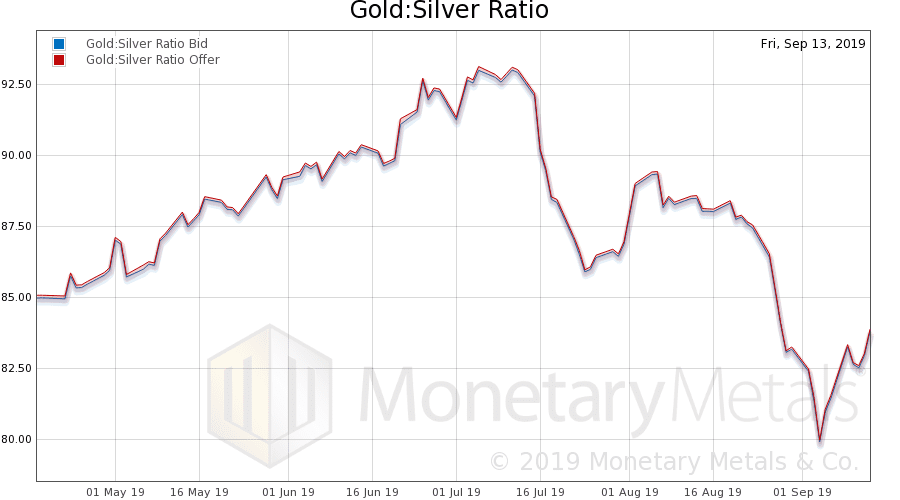

Next, this is a graph of the gold price measured in silver, otherwise known as the gold to silver ratio (see here for an explanation of bid and offer prices for the ratio). The ratio rose again this week.

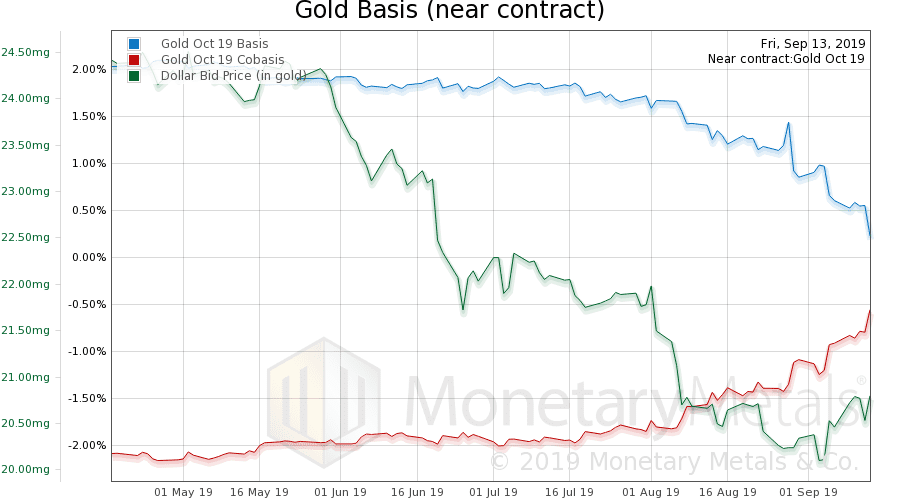

Here is the gold graph showing gold basis, cobasis and the price of the dollar in terms of gold price.

The October contract is very close to First Notice Day, yet the cobasis is still well under zero. No backwardation here, not even temporary backwardation. The gold basis continuous does not show the rise that expiring-October has.

The Monetary Metals Gold Fundamental Price fell $27, to $1,498.

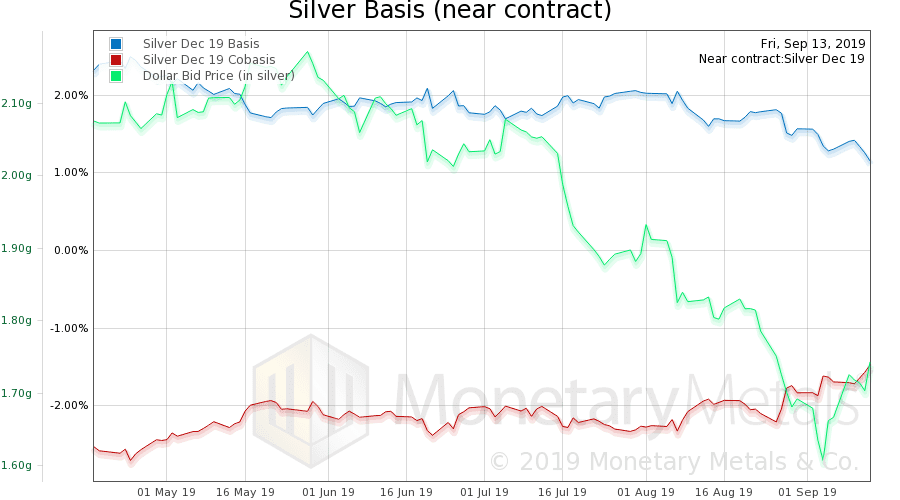

Now let’s look at silver.

The scarcity of silver (i.e. cobasis) rose a bit this week, and this is the December contract which is not near expiry.

The Monetary Metals Silver Fundamental Price dropped 73 cents, to $17.99.

I think silver it’s worth less than it was 50 years ago factoring in inflation. Gold is the same way although I do use it is a hedge short term. Long term both are terrible.