Bloomberg Vs. Navigant Research: Will EVs Produce A New Oil Crash? When?

Summary: In this article, I correct, update and extend the information contained in a previous contribution to put Bloomberg’s hypothesis that EVs will produce a new oil crash under scrutiny. The findings provide considerable support to this line of reasoning albeit conclude that the crash is likely to occur not by 2023 but by 2024. Here two game-changers can be identified: BEVs and electric buses. They would both account for almost 2/3 of the oil consumption reduction. It’s concluded that not one but many Li-ion battery gigafactories will be needed, and that much more lithium than expected will also be required in the years to come.

In recent days, there has been a great deal of discussion about the possibility that electric vehicle [EV] sales will produce a new oil crash. A series of reports by Bloomberg are at the center of this controversy. One can find them here and here. These views have been put into question by navigant research and summarized by green car reports.

Somewhat surprisingly, Bloomberg's contentions reinforce at least two of the views I put forward last year in another article.

First, that the worsening of climate change would have prompted the electrification of the automobile industry in the world as reflected in a decreased demand for diesel and gasoline which is likely to intensify in the years ahead as Tesla's (NASDAQ:TSLA) Li-ion battery gigafactory and other carmakers' gigaplants are introduced into the market.

Second, that even though oil prices won't fall forever, their recovery will take some time and it's highly unlikely that we will return to business as usual, which would nonetheless keep the incentives for persisting a search for substitutes intact generating a new downward impulse for the demand for oil.

Now, the main thrust of Navigant Research's arguments resides in four points. One, conventional vehicle fuel efficiency is meant to increase 22% over the next decade resulting in significant oil displacement to belittle the oil displaced by EVs. Two, autonomous vehicles will also tend to increase fuel efficiency on the roads further contributing to displacing oil. Three, assuming oil prices stay in the $40-$80 range for the next 10 years, conventional hybrids are likely to win the energy cost equation over electric drive. And four, low oil prices may lead to reforms which will have a negative impact on EV sales.

There are many problems with these ideas. To begin with, oil displacement due to fuel efficiency to belittle the oil displaced by EVs is nothing more than an illusion. For one thing, as early as 2014, there was an indication that gains in fuel economy in ICE vehicles were slowing. As of today, they even appear to be decreasing. In fact, average mileage per gallon for new cars and trucks in 2016 has been found to be 23.13, down from 24.79 in 2015 and from 24.1 in 2013. For another, it's not clear why major carmakers would be interested in making fuel efficiency improvements on internal combustion engine [ICE] vehicles rather than introducing electric ones to comply with fuel economy standards in the near future. Even though small improvements in fuel economy in ICE vehicles are likely to reduce significantly oil consumption mainly because of their weight in the global fleet, it doesn't necessarily follow that this will ensure compliance with Corporate Average Fuel Economy [CAFE] requirements. Indeed, as it has just been suggested, to meet these regulations in the U.S. in the next decade or so, "market penetration of hybrid and electric vehicles will have to exceed 15 percent for many manufacturers."

In the same vein, efficiency gains from autonomous vehicles will not make a difference until (at least) 2025. One reason for this is simply that their full driving capabilities will not be ready until then. In addition, one must be aware that for autonomous vehicles to be feasible, incentives to design more fuel efficient autonomous rule-sets will have to be established. As a recent peer-reviewed article suggests, in absence of these mechanisms, carmakers may end up designing a system to maximize speed and/or acceleration by default or as option which could actually worsen fuel economy. Another reason is that at present many global automakers don't seem to be convinced of self-driving cars' real viability and are asking the U.S. government to slow down on allowing them. These arguments are by and large shared by two specialized consultants who have just stated: "The real timeline for fully autonomous vehicles is closer to 10 to 15 years, and will happen in stages in line with the evolution of technology and regulations."

Furthermore, as I have shown in my latest article, there's an indication that conventional hybrid sales have been falling since 2013, whereas plug-ins have shown an exponential growth. Of course, a possible oil price rebound sometime this year could eventually help hybrid sales recover somewhat, but I doubt this will trigger a new long-term trend. I'm also hesitant to believe that oil prices will surpass the $65 per barrel barrier in the next decade or so. With oil prices in the $45-$65 range, the incentives for further electrification will remain intact. Under these circumstances, it's rather difficult to agree with Navigant Research that conventional hybrids will win the cost equation over electric drive.

Lastly, Navigant Research's fourth argument is both flawed and confusing. It's flawed because it doesn't take into account that oil prices are much more influential upon hybrid than plug-in sales, the reason being that the former are essentially aimed at reducing fuel consumption whereas the latter have more far-reaching objectives such as combating climate change and air pollution. It's confusing because it contradicts their previous assumption that oil prices could in fact attain higher (not lower) levels over the next decade.

Let's now return to our topic of discussion today, namely the possibility that EVs will produce a new oil crash in the world. Here we ought to ask ourselves by how much would the demand for oil need to be reduced for this to occur? According to Bloomberg, two million barrels of oil per day would be that tipping point. Note that this compares with Kuwait or Venezuela's oil production in 2009 or the increase of U.S. oil production between 2012 and 2014 (See Chart 3 and Table 4 in my SA contribution).

In this article, I enquire about the plausibility of Bloomberg's hypothesis that "electric vehicles could displace oil demand of 2 million barrels a day as early as 2023," which "would create a glut of oil equivalent to what triggered the 2014 oil crisis."

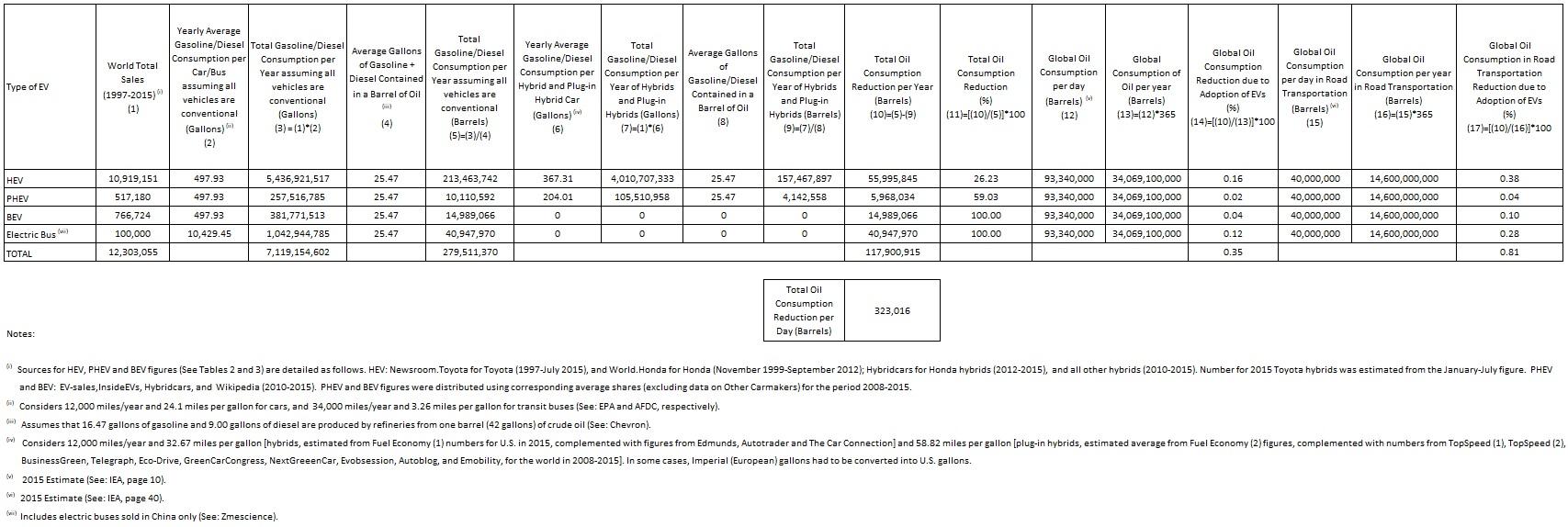

To do so, I correct, update and extend Tables 5 and 6 in my original piece as follows. Insofar as Table 5, the accumulated world total sales were extended to 2015 (Column 1) which resulted in new indicators for Total Oil Consumption Reduction per Year (barrels) (Column 10), Global Oil Consumption Reduction due to Adoption of EVs (Column 14), and Global Oil Consumption in Road Transportation Reduction due to Adoption of EVs (%) (Column 17). In addition, for comparison purposes, a new measure of Column 10 reflecting Total Oil Consumption Reduction per Day (barrels) is included. All of these modifications are presented in Table 1 below.

Table 1

Oil Consumption Reduction Due to Adoption of EVs

1997-2015

(Click on image to enlarge)

Sources: Newsroom.Toyota; World.Honda; Hybridcars; EV-sales; Insideevs; Wikipedia; EPA; AFDC; Chevron; FuelEconomy (1); Edmunds; Autotrader; TheCarConnection; FuelEconomy (2); TopSpeed (1); TopSpeed (2); BusinessGreen; Telegraph; Eco-Drive; GreenCarCongress; NextGreenCar; Evobsession; Autoblog; Emobility; IEA; and Zmescience.

Continue reading on Seeking Alpha.

Disclosure: None

Excellent work as always.