Washington At A Standstill: What Are The Risks For The Markets?

Image Source: Pixabay

With the US government shutdown, “fiscal QE” came to an abrupt halt. For two years, this mechanism had been directly feeding liquidity into the markets: the Treasury financed its deficits by issuing massive amounts of very short-term bills, which were immediately absorbed by money market funds, automatically inflating bank deposits and the M2 money supply.

In other words, the federal deficit acted as a veritable liquidity pump, neutralizing the Fed's restrictive effect. But by halting these issuances, the shutdown cuts off the financial system's main source of fresh cash. Upcoming auctions – and especially their settlements – are becoming stress tests: less cash flow, more pressure on repos, and increased fragility for the entire bond market.

I have regularly mentioned “fiscal QE” in my macro reports since June. I invite you to reread them to better understand the new mechanism put in place to finance the US debt.

For two years now, the M2 money supply has been growing again, even as the Fed reduces its balance sheet through Quantitative Tightening. This paradox can be explained by the central role played by the US Treasury and money market funds (MMFs). By financing its deficits through the massive issuance of very short-term Treasury bills (T-Bills), the Treasury injects cash into the economy: these issuances, which are immediately absorbed by money market funds, directly inflate bank deposits and thus the M2 money supply. This is a form of “fiscal QE,” which neutralizes the Fed's restrictive effect.

To put it simply, it is the US deficit that is currently fueling market liquidity. Its scale is such that it neutralizes the effect of the monetary tightening imposed by the Fed. In concrete terms, the federal government systematically borrows more than it repays, and this surplus flows into the economy via public spending. These funds directly inflate bank accounts before being channeled into money market funds or reinvested in the stock market. The amounts involved are staggering: the US Treasury now issues more than $1 trillion in new debt every 80 days, with a growing dependence on very short-term financing. Just 10 to 15 months ago, it took nearly 100 days to cross this threshold. The pace of debt accumulation has therefore accelerated significantly, and the US fiscal trajectory continues to deteriorate.

Every week, the pace intensifies: borrowing volumes increase while maturities continue to shorten. As a result, money market fund assets – which absorb this avalanche of liquidity – now exceed $7 trillion, forming a gigantic cash reservoir. Part of these funds is regularly redeployed to the equity markets, fueling the spectacular rise of large technology stocks and the explosion of margin debt, which is now at a record high. This “fiscal QE” has thus amplified the leverage that supports the entire market.

It is against this backdrop that the US government shutdown is now taking place. The Treasury is losing its ability to inject liquidity into the system: this “fiscal QE” is coming to an abrupt halt. Let's look at the historical statistics: the average duration of a shutdown is only eight days; in 86% of cases, the S&P 500 ends higher a year later, with an average gain of 13%. Even during the record 35-day shutdown in 2018, the index rose 11%. Each day of closure allows the government to defer nearly $400 million in spending, while the Fed generally adopts a more accommodative tone when economic data releases are suspended. In other words, shutdowns have historically been fairly well received by Wall Street. But the current episode is of a completely different nature.

This Thursday, October 2, the weekly sale of 4- and 8-week Treasury bills will take place. For the 4-week maturity, the Treasury is offering a record amount of $105 billion (settlement scheduled for October 7). Adding the usual 8-week issue, the total volume is expected to exceed $130 billion, making this auction a record in terms of value.

Under normal circumstances, money market funds absorb between two-thirds and three-quarters of issuances. The remainder goes to dealers, the large Wall Street banks that act as mandatory intermediaries. But this time around, MMFs may be more cautious, preferring to keep more liquidity available for fear of a worsening shutdown, anticipating a global reflux linked to the end of fiscal QE, and preparing for more difficult auctions ahead. Today will therefore provide a full-scale test of money market funds' appetite.

The real first test will come on October 7. If the shutdown continues until then, this settlement day will be closely scrutinized. Due to Bressent's strategy, which concentrates US debt on very short maturities, the Treasury will have to collect a record amount estimated at $250 billion in a single day – the equivalent of Qatar's GDP. If money market funds do not renew their positions today, a hole will appear in the financing, and dealers, forced to absorb the surplus, will have to refinance it on the repo market. However, if everyone knocks on the same door on the same day, repo rates can skyrocket – as they did in September 2019 – forcing the Fed to intervene via its Standing Repo Facility and other firewalls.

The longer the shutdown lasts, the greater the danger. In 2018, the federal deficit remained contained, debt had not yet crossed the 100% of GDP threshold, and the Treasury was financing itself more on a long-term basis. Today, the deficit exceeds 7% of GDP, debt is approaching 130%, and dependence on T-Bills is now structural. Cutting off this flow of liquidity through a shutdown, while the Fed continues its quantitative tightening, directly exposes the financial system to the risk of a crash.

Each auction becomes a stress test, each settlement a potential breaking point. A failure, particularly on the 7-year maturity, could crystallize mistrust and tip the entire curve, triggering global contagion: rising yields, pressure on the dollar, withdrawals from Japan and Europe, unrealized losses converted into forced sales, margin calls, and cascading liquidations. The real danger is not a US default, but the runaway momentum of a global financing mechanism based on the idea that Treasuries are the safest and most liquid asset.

We are still a long way from such an accident, but it is important to understand that the announced shutdown is not insignificant. It comes at a time when the US Treasury has become the central player in providing liquidity to the system. The longer the situation drags on, the more the pipeline seizes up – and the greater the likelihood of an accident.

In the short term, the markets are likely to continue to float, convinced that shutdowns always end up being positive. But this time, the mechanics are more fragile. Tech stocks are still hitting record closing highs, but in the event of bond market stress, they would be the first to be swept away in the wave of margin calls. Caution is warranted: comparisons with 2018 are misleading, as the fiscal and monetary context in 2025 is radically different. This time around, the potential consequences could be much more severe.

Against this backdrop of growing tensions on the US bond market, gold is naturally becoming a safe haven again. For two years, I have regularly pointed out in these columns that the loss of Treasuries' defensive role is profoundly transforming the architecture of portfolios. For more than forty years, Treasury bills have been the safest and most liquid asset. However, the sharp rise in interest rates and the collapse of the TLT index, which measures the performance of long-term bonds, have brought this cycle to an end. Unrealized losses on US bonds are colossal – nearly $600 billion according to the FDIC – and are weakening the entire financial system, as they remain bearable only as long as these securities are not liquidated.

It is precisely this risk of forced liquidation that is worrying the markets today. The shutdown is cutting off the flow of “fiscal QE” that has been feeding bank deposits and money market funds for the past two years. The sudden halt to this mechanism makes each Treasury auction more perilous and increases the risk of a liquidity accident in the repo market. In other words, Treasuries, which are supposed to be the most stable foundation of the system, have become a potential source of volatility.

Faced with this fragility, physical gold is increasingly seen as the ultimate defensive asset. Central banks – led by China and Saudi Arabia – have understood this well, reducing their Treasury portfolios to bolster their gold reserves. The persistent gap between gold prices in Shanghai and London confirms this sustained demand, revealing both supply tensions and strategic reallocation.

The decoupling observed between gold and Treasuries is not a mere market accident, but a sign of a structural shift. Gold is gradually regaining the role that US government bonds have lost: that of a universal safe haven asset, reliable in times of turmoil.

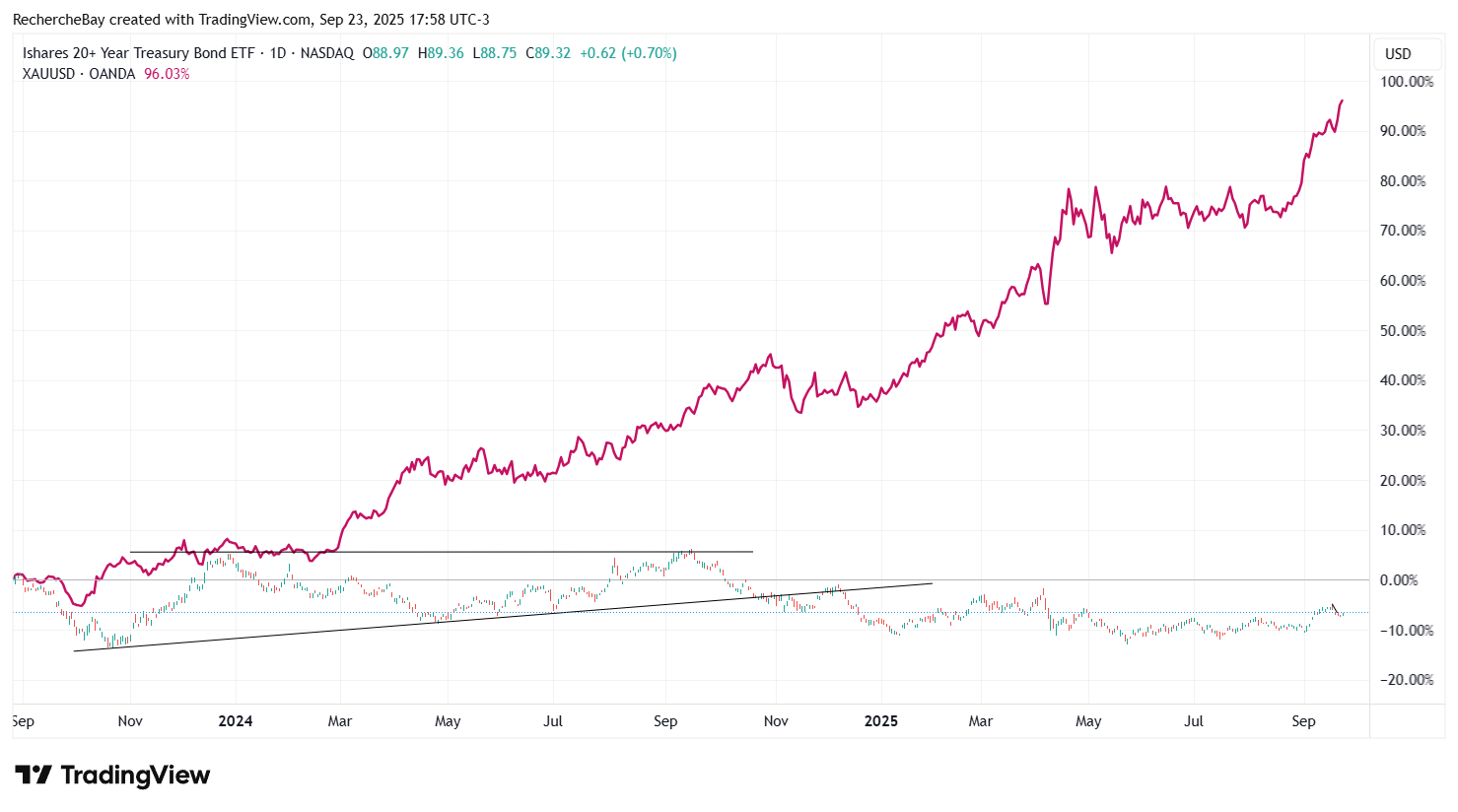

Gold's performance relative to Treasuries since 2022 speaks for itself. In January 2022, an ounce of gold was trading at around $1,800. Three years later, it is now trading at nearly $3,800, an increase of more than 110%. This surge reflects the renewed interest of institutional investors, the growing appetite of central banks, and the yellow metal's regained defensive role in a context of financial tensions.

(Click on image to enlarge)

Conversely, long-term US bonds have suffered a historic rout. The TLT index, which measures the performance of 20-year and longer-term Treasuries, has fallen by nearly 40% since 2022, recording the worst downward trend for US government bonds in forty years. For some maturities, particularly 30-year bonds, losses have exceeded 50%.

Never before has the decorrelation been so marked: gold has doubled in value at the same time as Treasuries, once considered the safest and most liquid asset in the system, have inflicted systemic losses on institutional investors. This shift illustrates a profound change in the cycle: gold is gradually regaining its role as a universal safe haven that US bonds can no longer fulfill.

More By This Author:

Gold And Silver Reset: Concerted Revaluation Of Strategic MineralsRecord Liquidity: How The Treasury Is Fueling The Stock Market Bubble

China Aims To Become Custodian Of Foreign Sovereign Gold Reserves

Disclosure: GoldBroker.com, all rights reserved.