The Truth About Negative Interest Rates & What To Expect

Negative Interest Rates

I have been pondering interest rates a lot recently, in light of where I think the economy is headed as well as current Fed policy. I mean, who hasn’t been thinking about it? The world is totally upside down with interest rates. And let’s not forget the paper (here, page 2) that became the keynote speech at the Chicago Fed gathering in late Spring 2019. It was proposed that had we lowered interest rates by 8-10% in 2009 (down to -3.00% area, yes negative) we would have totally avoided recession, and that this should be the blueprint for the future. It’s actually an admission that the so-called recovery from the GFC is no recovery at all and that it won’t work this time around either. No, this time is not different.

In any case, I'd like to share my negative interest rate theory with you, with regard to negative nominal interest rates and bonds. It seems that publicly, no one else talks about negative rates, save for a few like Jeff Gundlach, Peter Schiff, Michael Pento, Steve Keen, Jeff Snider, and a couple of others. Whereas CNBC and Bloomberg bombard us that negative rates are the new normal, these men all say that negative rates don't make sense because who wants to lend money with a guaranteed loss? I think there is more to it, and there are some subtleties that are missing from the public discourse, and certainly never discussed even in general in the mainstream financial media.

So here goes…

Investor Demand For Bonds

With regard to bonds, we expect a certain range of yields to balance the risk versus reward. The ten-year treasury, for example, is our usual standard-bearer at around 6%, to offer a "risk-free" annual return. It’s not risk-free. It’s really the “lowest risk” (I disagree), but that is not for this discussion. For now, the ten-year at 6% shall remain the standard-bearer. Raise the risk with other assets, and we expect a higher return. Single-A corporate bonds might trade over a 7% yield by comparison, BB at 8.5%, and common stock on average might offer 10%-11% when including the dividends.

If the bond yield is too high, it indicates that the risk is also too high, and the demand by investors for that bond will fall until the yield reaches a certain elevated level and there will not be any demand found, or as Wall Street would say, it won't catch a bid. This means that as the demand falls, the price will also fall until the risk-reward profile becomes attractive enough for investors to buy at market value. With very rare exceptions, if the price falls, the yield must rise.

In the past, we have seen particular issues lose their bid, even as the market interest rate was rising, but eventually, they caught a bid when the yield rose to what we colloquially call "in the stratosphere". Puerto Rico at 12 cents on the dollar and Greece at 40+% yield both come to mind. Of course, there have been single issues that never catch a bid, in such circumstances as default and/or hyperinflation.

On the other hand, as the entire bond market experiences rising prices and falling yields, we will find more investors who will buy lower-yielding bonds, who in the past would not have bought a bond at the same low yield. That’s because investors expect to make up the lost yield on the ability to sell the bond for a profit at a later date. This transpired over the last 40 years as yields in America fell from around 20% to where they are today at 1.50-2.00%.

Most recently, as yields have plummeted around the world, investors have tried to catch a falling knife, bidding up the price of bonds while creating further downward pressure on the yield. Austrian bonds come to mind. C-rated bonds yielding 4% will now catch a bid because a treasury yields only 1.50 % and a muni bond is not much better.

We must also consider that current federal law requires certain financial institutions to buy the lowest yielding treasuries (really all treasuries), such as life insurance companies who are required to hold a very high percentage of treasuries, regardless of what the nominal yield may be. Other financial institutions have the same or similar requirements, such as banks, investment banks, primary dealers, and the like. This adds upward pressure to the price because there are buyers who are ready, willing, and able to comply with the law. Upward price pressure, again, translates into downward yield pressure.

This all holds true even if rates fall below 0%, because of the laws requiring financial institutions to buy at any interest rate, as well as traders at the bond trading desk at the institutions thinking they can day-trade or swing-trade a greater return than what they'll lose on the negative yield. If they buy a new issue bond at -0.10%, they know they'll get a premium for it when the next round of new bonds will offer -0.20%, and the premium they receive to sell will be greater than the negative yield. This holds true even when including the premium they paid for it, because if they trade at a loss they lose their shirt (and their job).

However, if the nominal yield is a greater loss than the gain on that trade, demand for the negative-yielding bonds will dry up pretty quick because traders won't be able to profit on the day-trade or swing-trade. I suspect that yields just below zero will not have this problem, However, there is an inflection point below that, at which traders will stop trading, somewhere between -0.01% and -100%. That inflection point is probably much closer to zero than it is to negative 100%.

All of this will have to be relative between where the trader is domiciled vs what he can get in the rest of the world. A trader in the Eurozone, for example, may be able to get a -1.00% on his German Bund, which makes the treasury look great even if it is also nominally yielding a negative return, so long as that return is closer to zero on the treasury. (At this point I'd like to leave out the exchange rate and relative dollar strength. That will complicate the matter too much, not allowing us to understand what is happening.)

All of this only works, so long as inflation remains low or we don’t experience stagflation. If inflation runs high, there will be a progressively shrinking desire for negative-yielding bonds, even if the trade profit is greater than the yield loss, because inflation will wipe out the remaining trade profit. However, even in a deflationary environment, the bond itself loses purchasing power with a negative yield, and so long as the absolute value of deflation is greater than the absolute value of the negative yield, traders will remain interested in the bonds for a longer period as their purchasing power increases with both the trading profit as well as the gain in purchasing power. That said, no one wants to see their account balance falling even in this possible scenario of negative yields being lower than deflation and purchasing power still increases, so this will not be tolerated very long. And if the deflationary period is transitory as central bankers will desperately try to make possible, then bond traders won’t go for it at all.

While the possibility of negative-yielding bonds combined with deflation exists, it will not last very long if it happens. The negative yield destroys capital, which is certainly deflationary as well. As this happens, bond investors will wake up to the problems this causes for the local fiat currency (in our case, USD), and a crisis of confidence in the fiat currency will begin to form, causing investors to sell the fiat currency.

Central bankers of the world will not tolerate this scenario and they'll pump as much cash into circulation as they deem necessary, wiping out any deflationary forces with ten-fold inflationary forces. Regardless of the nominally stated yield on any bond, the real yield in the market will move significantly higher.

Because the yields will rise, the price of those bonds must commensurately fall, which is also destructive of capital. For a short period it may actually cause a feedback loop of rising real yields and deflation of asset values, but a rise of prices in the market place. And this will be especially true of retail borrowers who will think they’ll be able to acquire capital at a negative yield (mortgages, student loans, and car loans), but in reality they’ll only be offered rates reminiscent of the early 1980’s.

Borrower Supply Of Bonds

All of the above is for the lender’s/investor's demand side of the bond market, their desire to lend cash in the form of bonds. As for the borrower's supply side, their desire to borrow in the form of bonds:

Bond issuers want to offer to borrow capital at the lowest rate possible because it will have to be reinvested back into their business for the greatest possible return. This must be true in order to remove the risk, or at least lower the likelihood as much as possible, of default for both the borrower as well as the lender. No one wants default. But the borrower also knows that investors won't lend unless appropriately compensated for the risk they are about to take. Therefore, the borrower must offer something reasonable in return for the risk taken.

However, if the nominally stated yield on the bond is too high, borrowers know that anyone willing to lend may become skeptical of the high yield, even after looking at the company’s financial statements. The lenders will ask themselves why the yield is so high, what is the risk buried beneath the surface that is causing this borrower to offer a higher yield?

The higher the nominally stated yield goes, at first the willingness of lenders increases. But eventually, there is an inflection point at which the lenders second guess the loan and the supply of capital will begin to reduce as the yield goes too high. Borrowers may even misinterpret this as the yield they offer not being high enough, and they may offer an even higher yield to entice lenders.

On the other hand, if the yield falls below zero, borrowers may still have access to borrow capital for the reasons stated above, namely that relatively the yield may be higher than the other available options and also that the bond traders think they'll trade a return that is greater than the negative yield loses. Remember, to borrow a phrase from Grant Williams, certain financial institutions are legally required to hold this "return-free risk".

Here too, however, there is an inflection point because borrowers know that lenders only lend at a profit. If the yield will lose more than the trade can gain, borrowers will lose access to capital. knowing this, they will slow the pace of how much they offer as the rate falls further below 0.00%.

In addition, eventually, institutional investors will rally together to force Congress (or their own sovereign legislative body) to change the laws regarding how much of this they must be forced to legally own; they have a fiduciary responsibility to fulfill pensions, life insurance claims, annuity promises, and the like, and with negative-yielding bonds making up the supermajority of their portfolios, they can not possibly fulfill all those promises.

As far as borrowers are concerned, they really don't care if inflation runs hot because inflation favors borrowers as it becomes cheaper and cheaper to pay back their creditors. Borrowers are more concerned with deflation because it will become more difficult to pay back the loans, which is complicated by the fact that people will have falling income with deflation and won't be able to spend as much on the products and services which the borrowers offer.

Low rates are problematic. Low rates discourage saving and investing, and people will tend to spend their cash faster instead. This sends a false signal to businesses who will then think that because interest rates are so low and because consumers are spending faster, they should actually try harder to borrow the cash at the lower rate to grow the business or invest in efficiencies to further increase profits...they should strike while the iron is hot. So too, if interest rates rise too high then businesses get a false signal because consumers will save more and businesses will see less profits, and therefore borrow less at the higher market rate in order to conserve capital. They’re sort of right to try to borrow with lower rates because they can borrow the same amount of cash for lower service. So too, higher rates make it harder to service the same capital.

In reality, though, businesses should be borrowing when rates rise, because consumers will invest their savings with the higher offered nominal rate. With the long term profits the savers make on the higher yields, they'll be able to buy much more stuff, even right now with the higher income. This is similar to the stock market wealth effect, that when stocks reach lofty levels, people feel more wealthy and tend to spend more. So too, when interest rates fall, businesses should tighten their belts because that will signal consumers are getting ready to invest less and therefore spend less in the long run, not the opposite as they often misinterpret.

Another point to consider is that if I use a bond calculator to find the price of the bonds I hold, it will tell me the price of my bond relative to the market for bonds. Even if my bond has a negative yield, as long as the market yield is lower than mine, my bond is worth more in the market. The problem is that a bond calculator is not calculating the net present value of all future cash flows in conjunction with what I’ll be paid back at maturity for the bond. Rather, it only calculates relative market price, which is useful only to know approximately what I can sell it for right now.

Unfortunately, that bond calculator misses the point for bond investors who rely on the future cash flows for income. For me as the investor, who needs the future cash flows to pay my expenses, I need to calculate the net present value of the bond. I can't calculate the NPV because with a negative interest rate, the bond will have a negative price instead of positive. For example, if I invest $1000 for 3 years at -5.00%, the NPV will be almost -$1200. If my bond has a negative yield I get back less than what I invested, which is the complete opposite of what I want.

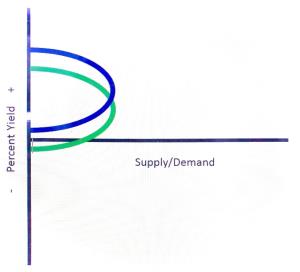

I have included an investor/lender demand graphic representation (not drawn to scale) of the demand for lending in the form of bonds. It represents what I’ve written above, that if the yield is too high, investors will not invest. If it is too far below zero, so too they won't invest but for different reasons.

The peak demand for investors is on the right side of the blue parabola, as is peak supply from borrowers. Investors would really like an infinitely increasing yield and the higher the yield the more they will invest. But investors are realistic and know that once the yield is too high, the risk also begins to increase uncomfortably.

From one investor to the next, this graphic will not be correct, as some investors will only invest with a higher yield than the market offers on low-risk assets, some investors just concern themselves with cash flow, etc. While my graphic may be generally true for the market as a whole, on a case to case basis it will never look like this. Also, there is a limited supply of capital being offered, which is not represented in the graphic.

The second graphic is the same but for borrower's and the supply of bonds being offered in the market. This shows what I wrote above for borrowers, that if the yield is too high they would rather not borrow because it becomes too expensive and eats up their profits. They want a lower and lower cost of borrowing capital. The lower the cost to borrow, the more they want to borrow (within limits because they don't want to borrow unlimited amounts of capital without a commensurate ability to deploy and service it, and this is not represented in the graphic).

Borrowers also understand that they won't find any lenders if they go too low and therefore don't even offer to borrow because the risk is just too much for investors not to have a reasonable return to compensate the risk. Even though borrowers would love to go to lower levels below zero, they stop offering long before those levels knowing they won't find lenders.

This too will change from one borrower to the next because some will have a higher tolerance for higher interest rates if they think their project will give exceptional yields on their investment, others will borrow at any cost, some won't borrow, some will only borrow if the terms are much more favorable, etc. Here too, my graphic may be generally true for the market as a whole, on a case to case basis it will never look like this.

Market Supply of Funds for Lending by Investors (Demand for Bonds) & Market Demand for Funds to be Borrowed by Corporations (Supply of Bonds)

Both models are exactly the same shape for the market. However, each and every individual, regardless if investor or borrower, will have a differently shaped curve depending on their need for capital and income, and their appetite for risk versus reward.

The vertical axis represents the percent yield, with the vertex at 0.00%, above the vertex is a positive yield, and below the vertex is a negative yield. The horizontal axis represents the quantity of both the supply and demand for bonds. The green curve represents the institutional market, and the blue curve represents the individual market.

Because individuals generally buy bonds for the income, they will not tolerate a negative yield (with an implied guarantee of loss of principle), therefore, their demand lies only in positive territory. Individuals generally don’t trade bonds either; they buy and hold to maturity. So too, the issuers who supply the individual market are aware of this dynamic. The institutions make up the overwhelming majority of investment in the bond market (households - 12%, foreign investment which includes more institutions - 26%, domestic institutions - 62%), and they are willing to go into negative-yielding territory for the reasons stated above.

It is my hope that this will help clarify what is really happening with the bond market and why, as well as what we may expect going forward. I am only an individual and I can only report what I see happening, and then try to interpret what lies before my eyes. I welcome all comments and questions, and I look forward to hearing what you have to say as well as the ensuing discussion that follows.

Disclaimers: The contents of this article are solely my opinion, and do not represent neither the opinion of this website nor its owner(s), nor any employer whether by contract or for wages. ...

more

Nice take on bonds. Banks don't want nominal negative bonds and neither do individuals.

Thanks for reading and commenting Gary. I appreciate your feedback and contribution to the discussion.

I don't think anyone wants negative yielding bonds because of the guaranteed loss. Imagine if I asked to borrow $10 on condition I have to pay you back $9.75. You might as well just give me the quarter and call it a day without having to risk the other $9.75 not getting paid back.