Stocks Aren’t Cheap

Image Source: Pexels

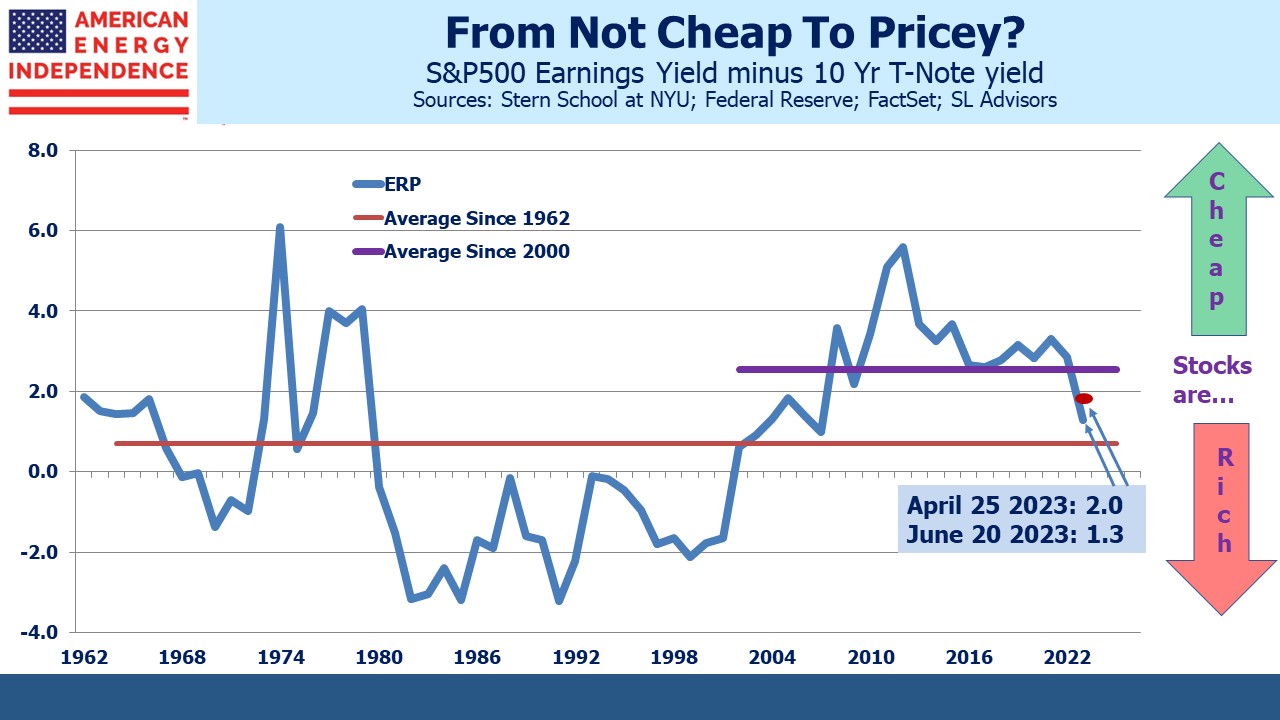

The Equity Risk Premium (ERP) is a measure of the relative attractiveness of stocks versus bonds. It compares the earnings yield on stocks with the interest rate on ten year treasury notes. For much of the past decade, it’s shown stocks to be relatively attractive compared to the average relationship going back to 1962 – of no particular significance also my entire lifetime.

Quantitative Easing (QE), first unveiled with acute insight by Fed chair Ben Bernanke during the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) and abused by successive Fed chairs ever since, made bonds unattractive. QE has evolved from a unique solution to a banking crisis into a form of partial Federal debt monetization. The problems facing regional banks trace their roots to many banks mistakenly concluding that if the Fed was loading up on long-term bonds that must make it acceptable to do so. This suspension of critical thinking exposed the absence of competent risk management. America’s more than 4,000 banks have a greater need for chief risk officers than the pool of qualified candidates can supply.

Since the founding of your blogger’s firm, SL Advisors, in 2009, stocks have represented the only meaningful source of return. Bonds have had some good years because the Fed has more or less adopted permanent QE, at least judging from their balance sheet. Repeated promises to kick the QE narcotic habit have done little more than impose a brief pause in the inexorable growth of the central bank’s bond holdings.

The Fed’s eventual zeal to vanquish inflation has over the past year or so improved the relative appeal of bonds. But fixed income investors must still compete with return-insensitive foreign central banks, pension funds with inflexible investment mandates that require bonds, and our own Federal Reserve with its bloated [$8TN] in holdings. Bonds are a long way from cheap. Ten-year yields of 3.75% remain inadequate compared with long-term inflation unlikely to return to 2% and a Debt:GDP ratio heading relentlessly up. But some might agree that yields on shorter maturities justify the discerning investor in considering modest exposure. Treasury bill yields above 5% almost seem like a fair return, provoking nostalgic recollections of the time value of money and the “float” banks make on the days required in processing checks.

Last year we responded to the lethargy with which Charles Schwab Bank and its peers raise deposit rates by sweeping client cash into two-year treasury notes. More recently our Florida homeowners’ association moved its funds in excess of working capital out of a parsimonious 2% bank “savings” account and into the glorious bounty of 5.25% 90-day treasury bills.

In April when we last examined the ERP, we concluded that stocks were not cheap. Behavioral finance teaches that overconfidence afflicts too many investors. Opinions come with much wider confidence intervals than are usually acknowledged. Humility among investors is acquired while learning this, if fortunate at only modest expense. There are many ways to value the market, some of which probably make it appear cheap. The ERP is not a secret.

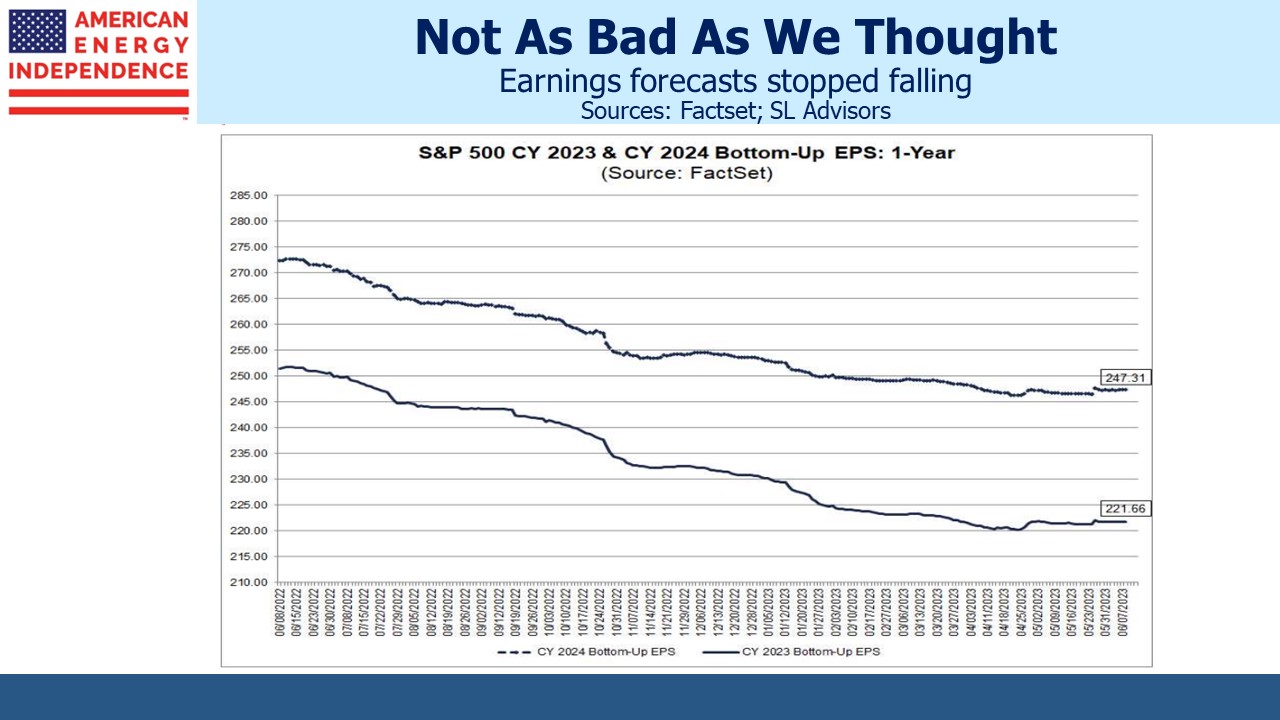

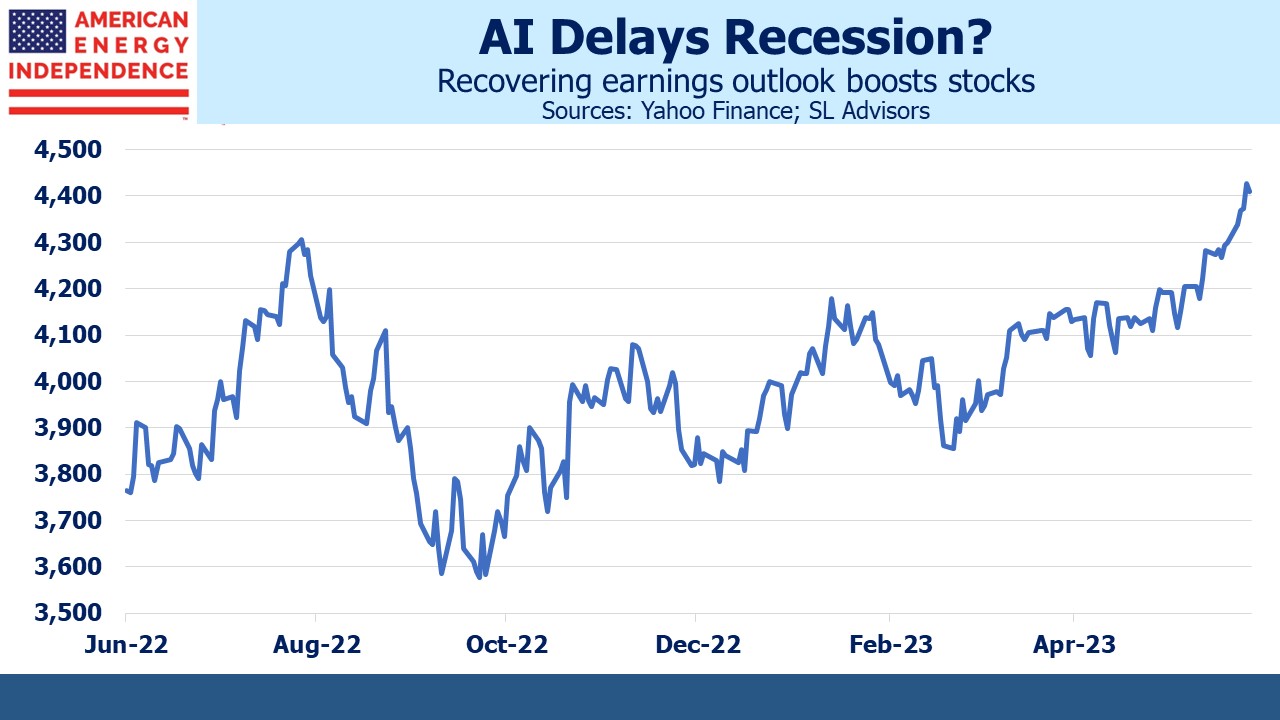

Since April, earnings forecasts have stopped falling. This stabilization has offered hope that the recession promised for later this year will be postponed, helping propel stocks higher. The yield curve has similarly responded. At one point during the demise of Silicon Valley Bank, traders were betting on a Fed Funds rate below 3% by the end of next year, suggesting a cut of almost 2%. More recently, Fed chair Powell’s warning of a couple of years before rates come down left many unconvinced. But traders have shown him enough respect that the ignominy of a premature capitulation on inflation has been quietly shelved.

Stocks have looked beyond the end of declining earnings forecasts and anticipate upward revisions. Expected growth in profits for next year has moved above 10%. However, when stock prices and bond yields rise together, the inevitable casualty is equity valuation. Whatever you thought in April, an S&P500 at 4,400 is less appealing than the 4,100 of two months ago.

We’re not about to eschew stocks to become bond investors. There’s no alternative to equities for investors who wish to preserve their capital’s purchasing power. Tactically switching out of stocks and back in requires two good timing decisions. Taxes on realized gains make it even harder.

At the risk of repeating an admonition frequently offered on this blog, midstream energy infrastructure stocks remain dirt cheap. Ample dividend coverage, continued financial discipline, and pipeline tariffs that are often linked to inflation make this a sector whose entry needs no skill at market timing. We’re not selling anything.

But for the investor with cash to invest in the broader market, we’d suggest that the need for action is not urgent. Today’s entry point is likely to be available again, and perhaps better ones too.

More By This Author:

Situations We’re FollowingMore Thoughts On Oneok and Magellan

Oil And Pipelines Less In Sync

Disclosure: We are invested in all the components of the American Energy Independence Index via the ETF that ...

more