"It's Just Absolutely Incredible": What's Going On In The Corporate Bond Market Is Stunning

In a recent report from hedge fund giant Brevan Howard, the investor pointed out the biggest flaw in the policy response to the covid pandemic: "Many businesses face solvency risks that are not addressed by borrowing; a debt overhang cannot be cured by more borrowing no matter how cheap it may be."

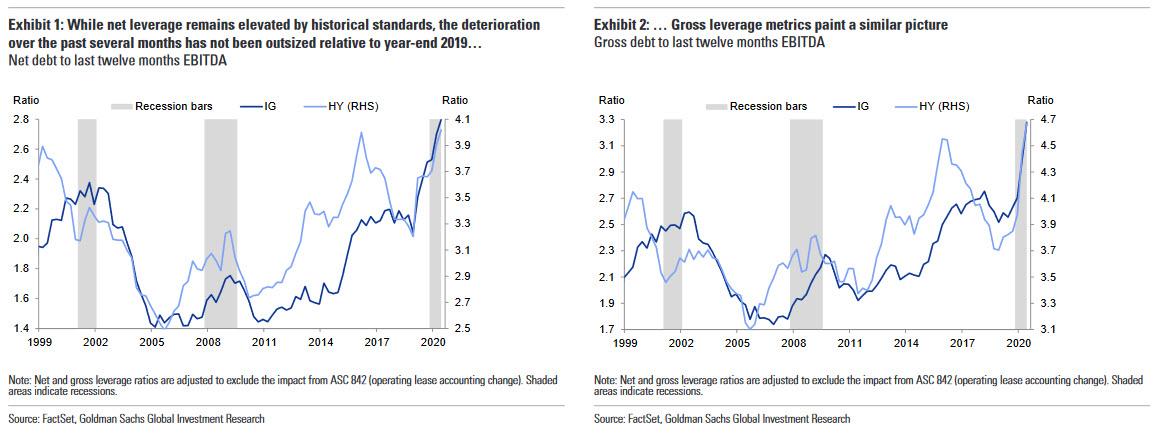

While that statement is absolutely true, and it applies not only to the aftermath of the covid shutdowns but everything that has happened in the past decade, it hasn't stopped both government and corporations from going on a historic borrowing spree, in the former case thanks to "helicopter money" whereby central banks now directly monetize all the debt government treasurys have to sell, and in the latter as company CFOs take advantage of record low rates to borrow as much as possible before the window closes. This can be seen in the Goldman chart below which shows that both investment grade and high yield leverage is at all time high levels:

The numbers are staggering: on Friday, BofA Chief Investment Strategist Michael Hartnett calculated that US corporate bond issuance is currently annualizing a mindblowing $2.5 trillion this year, between $2.1TN for IG and $0.4TN for high yield. As Bloomberg writes today, while much of that fresh cash - more than $1.6 trillion in total - has helped scores of companies stay afloat during the pandemic lockdown, "it now threatens to curb an economic recovery that was already showing signs of sputtering" as many companies will have to divert even more cash to repaying these obligations at the same time that their profits sink, leaving them with less to spend on expanding payrolls or upgrading facilities in months ahead.

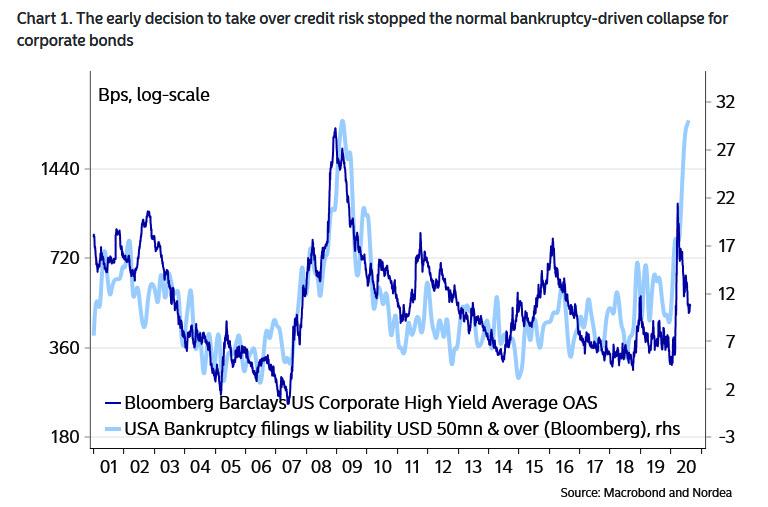

The paradox is that this is all by design: in doing everything in its power to prevent the corporate debt bubble - which was already at a record size before the covid pandemic - from bursting, the US central bank unleashed monetary policies that have terminally decoupled the bond market from all fundamentals, while also arresting default risks by taking over credit risk without punishing investors and moving into lower-rated debt than ever before, which started off the risk-on period as Nordea's Andreas Steno Larsen writes today and shows in the following chart:

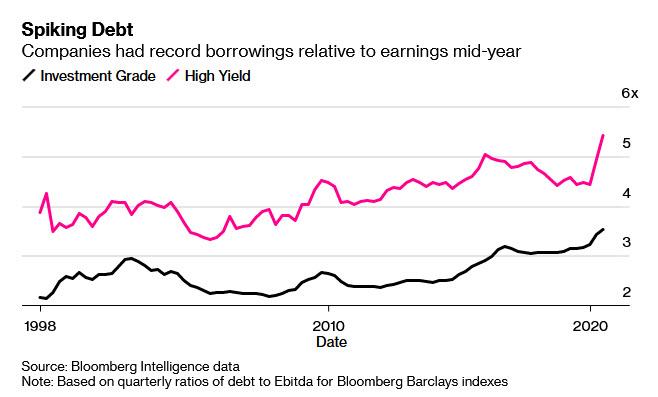

In a sign of just how pronounced the borrowing overhang has become, Bloomberg points out that the average junk-rated company had debt levels relative to earnings that were so high in the middle of the year, according to a new analysis by Bloomberg Intelligence, that they almost would have tripped do-not-touch alerts from banking regulators a few years ago. Those warnings back then only applied to a handful of borrowers. Had regulators not opted to drop these warnings, they could today apply to far more.

Corporations have also been borrowing heavily as the Fed has slashed short-term interest rates to near zero and supported credit markets through, for example, buying company bonds. Lower rates have spurred investors to buy higher-yielding, riskier securities, which has allowed even junk-rated firms to borrow more to tide them over during the crisis. High-grade issuers have already sold more bonds in 2020 than any other full year in history. Junk corporations have surpassed 2019’s total already.

Some specifics: leverage (i.e., the ratio of total debt to Ebitda) for investment-grade companies was 3.53x in the second quarter for the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Corporate high-grade index. That’s the highest in data going back to 1998, and is up from 3.42 in the first three months of the year, when the impact of the pandemic was only just beginning to show up in earnings. It compares with a 20-year average of 2.65.

For high yield, leverage stood at a record 5.42 at the end of June, up from 4.93 at the end of March and 4.44 at the end of 2019. Avis Budget Group Inc., the car rental company, had debt equal to 27 times earnings as of June 30, up from five times at the end of March, as it burned cash in the second quarter, although that figure could improve later this year as its earnings start to rebound. In 2016, banking regulators pushed back against leveraged buyouts that left companies with ratios above six.

No matter how one slices the data the message is clear: "An overburdened corporate sector is likely to grow less rapidly and that could slow the whole recovery down," said Kathy Jones, chief fixed-income strategist for Charles Schwab.

Of course, none of that matters now when rates are at all time lows, but fast forward a few years when inflation kicks in and suddenly corporate America is facing another unprecedented crisis as it has to not only rollover record amounts of debt but has to refi into ever higher rates.

Quoting Lale Topcuoglu, senior fund manager at JO Hambro Capital Management in New York, Bloomberg warns that a slower recovery could have wide-reaching implications in financial markets. Many securities prices reflect investors’ expectation that profits will normalize next year, when in fact it could take at least two or three years. Not surprisingly, she believes that many junk bonds as being overpriced.

"It just seems absolutely incredible how much people are closing their eyes and buying," Topcuoglu said.

The good news is that unlike last year when much of the new debt issuance went to fund stock buybacks, much of the debt sold in recent months has refinanced maturing borrowings allowing companies to lock in even lower rates for the next 5 to 10 years; furthermore many of the companies are holding on to the money they raised as cash and may end up not spending it.

And while the fact that companies managed to stay afloat during the pandemic is "a good thing compared with the alternative of even more corporations having gone bankrupt" not all companies have been able to access that credit, with smaller borrowers often getting shut out as a DoubleLine Portlio Manager wrote WEdnesday in "Large Firms Reap Benefits From Central Bank Easing As Small Ones Suffer."

To be sure, even the large companies face a day of reckoning or as Bloomberg puts it simply "a hangover" as many corporations were already groaning under their debt loads even before the Covid-19 pandemic, and now will have to work harder to cut borrowings as earnings remain depressed. Even if companies are hanging on to the money they borrowed, they must still pay interest on it, and could eventually use the cash if the pandemic drags on. Many will simply revert to using the debt proceeds to repurchasing their stock and make quick profits for management and shareholders as we pointed out earlier this week. Ultimately it is the economy, and the middle class workers who will suffer the most as chief JPM economist Michael Feroli wrote, warning that with corporations shunting more of their earnings toward paying interest and paying down debt, they will struggle to hire and invest as much as they would at the end of a more conventional recession." That could translate to a relatively sluggish recovery instead of the fast, “V-shaped” one many investors hope for.

"The debt overhang is going to be a headwind for capital spending and for hiring, not just in the second half of the year but probably into next year as well," Feroli said.

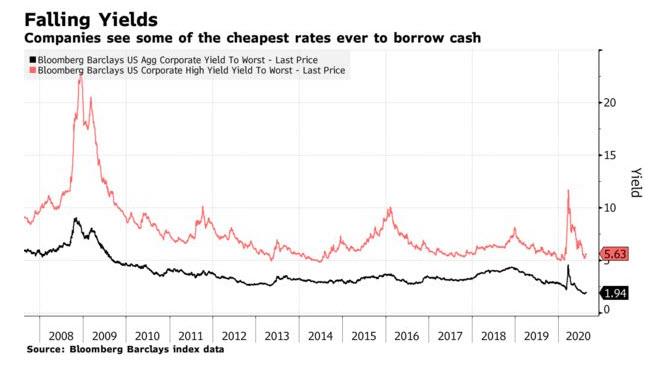

Another paradox is that as corporate leverage is rising to all time highs, rates continue to sink as investors have no choice but to buy their debt, which in turn forces even more debt issuance, even higher leverage and so on, until the Fed is tasked with yet another corporate debt bailout:

With short-term interest rates having fallen to near-zero levels, borrowing is cheaper for most companies than it was just a year ago. Average yields on U.S. investment-grade corporate bonds touched all time lows of 1.82% earlier this month, and are still hovering near those levels, according to Bloomberg Barclays index data.

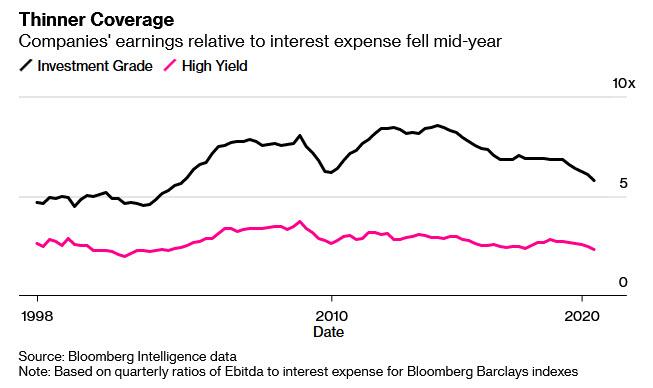

As a result of record low rates, even as leverage soars, interest coverage, or EBITDA to total interest expense, has fallen to 5.8 in the second quarter for investment-grade companies, compared with a 20-year average closer to 7. The June 2020 level was the lowest since 2003. For junk-rated companies, the interest coverage ratio fell to 2.3 in June, also the lowest since 2003.

Unlike the 2008 bubble, ratings firms have taken note of the broad downward trend in credit quality, with S&P downgrading more high-yield debt in the second quarter, relative to upgrades, than any time in at least a decade, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. That too has not stopped investors from piling on: just recently junk-rated Ball Corporation sold debt for the lowest ever yield for a "high" yield bond at 2.875%.

Meanwhile, corporate earnings per share fell by about a third in the second quarter from the same period last year, and are likely to fall in the third and fourth quarters as well and may not recover their 2018 levels until the end of 2021. As a result, strategists expect leverage and interest coverage to erode further.

None of this fazes investors who have gone "balls to the wall" buying corporate debt with the Fed's blessing now that the central bank is buying both investment grade and high yield ETFs and bonds in the open market. To justify the euphoria, investors have given companies a break for about a year and are looking ahead into mid-2021 or even later to evaluate where they will perform after, for example, the world finds and distributes a Covid-19 vaccine. That to Bloomberg explains why cruise companies that are burning cash, such as Royal Caribbean Cruises Ltd. and Carnival Corp., have been able to borrow repeatedly, and have seen most of their new bonds trade well above the price at which they were originally sold.

But even if bond prices are broadly rising, investors need to be cognizant of the risks they’re buying, said Schwab’s Jones.

"This cycle is very different because we’ve had so much support from central banks and we have so much liquidity in the market," Jones said. "But the old saying ‘liquidity does not equate to solvency’ is something people need to keep in mind when they’re investing."

Brevan Howard would most certainly agree.

We give the final word to GnS Economics' founder Tuomas Malinen who today writes that "we have stock markets that have decoupled from real economic activity to an unprecedented degree and a moribund European banking sector practically doomed to collapse. The constant resuscitation and bailouts of the central banks since the last crisis in 2009 have pushed us to the brink of‘Financial Armageddon’, initiated this time by the repo-market implosion and the coronavirus pandemic."

His conclusion: "When it truly gets going, as it likely will, do not blame the virus. Blame the reckless central bankers."

Disclaimer: Copyright ©2009-2020 ZeroHedge.com/ABC Media, LTD; All Rights Reserved. Zero Hedge is intended for Mature Audiences. Familiarize yourself with our legal and use policies every ...

more

Well said Tyler. I really impressed with you. Many thanks James