Is Stagflation Risk Real?

A few days ago, I had the pleasure of attending the Hoover Monetary Conference – I would call it a Powwow of central bankers, if there had not been an actual Powwow a few steps outside the venue. While Hoover is known to reflect “hawkish” views, “hawks” and “doves” alike used the question of whether the Fed is “behind the curve” to argue all things inflation and stagflation. I left the conference more concerned about the risk of stagflation; let me explain.

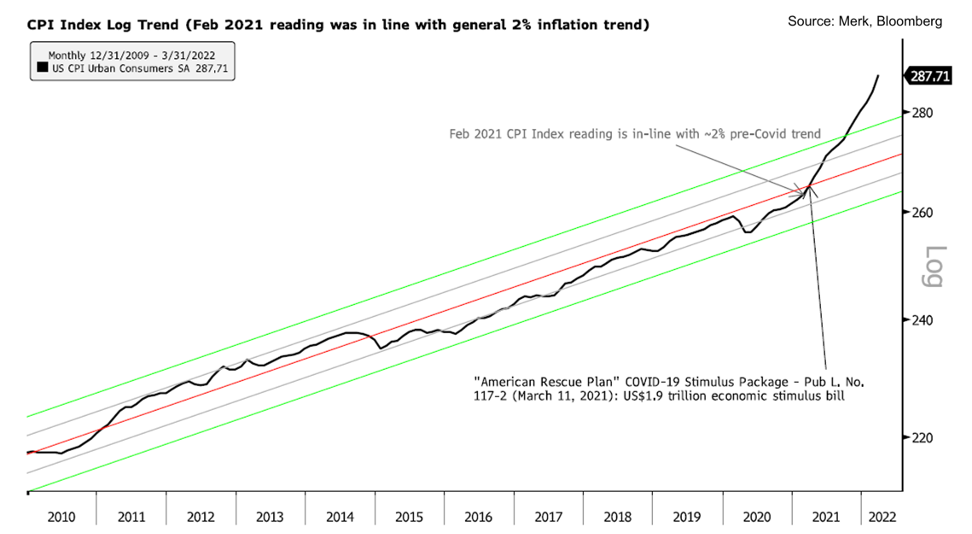

The “hawkish” view was well represented: the Fed has fallen behind, and even generous Taylor rule models (an econometric model that describes the relationship between Federal Reserve operating targets and the rates of inflation and gross domestic product growth) suggest rates should be much higher. Former Treasury Secretary, Larry Summers, and Hoover’s John Cochrane and Tyler Goodspeed each showed how they believe fiscal policy (“fiscal helicopter drop”) has been a key contributing factor to the inflationary surge we have seen:

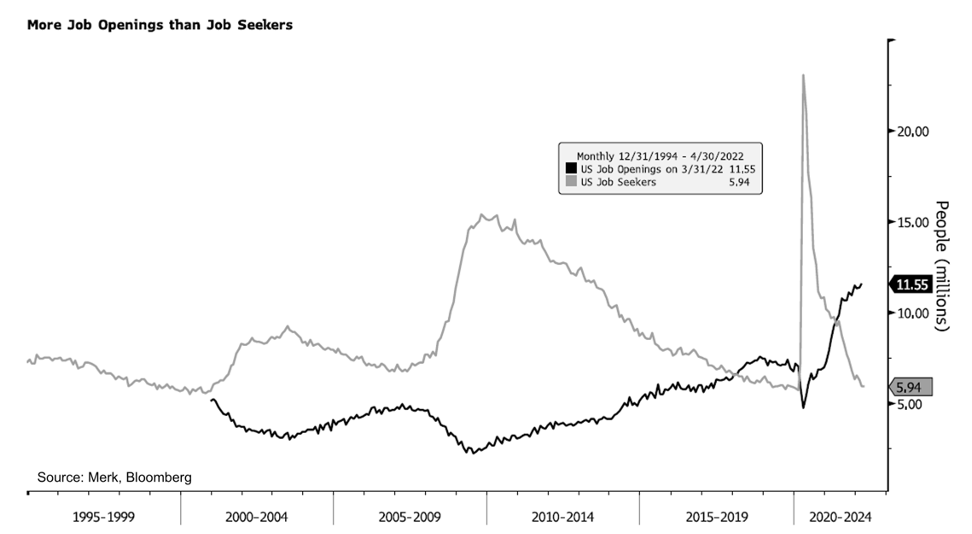

Larry Summers took it several steps further, warning that when you have twice as many job openings as job seekers, you have a job market that is unsustainably hot and that when monetary policy continues to be accommodative, you are asking for major problems:

Summers argued there needs to be a new framework to have the public regain confidence in the Fed’s inflation-fighting abilities.

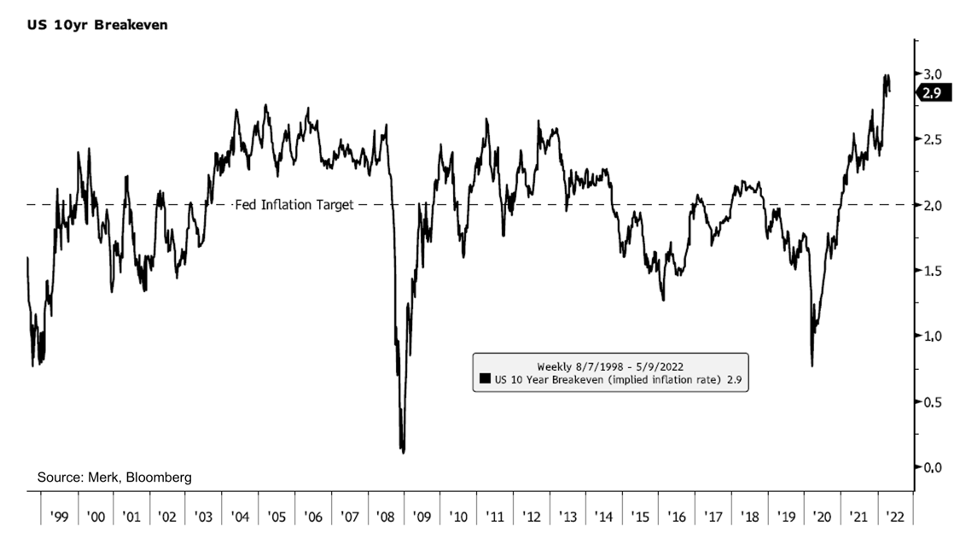

But, but, but…. even hawks acknowledge that while inflation expectations have risen to concern levels, we are not at a stage where the public has lost confidence in the Fed:

* The breakeven inflation rate represents a measure of expected inflation derived from 10-Year Treasury Securities and 10-Year Treasury Inflation-Indexed Securities.

No one knows where inflation will be a decade from now. The hawks that stipulate that the market still has confidence in the Fed rightfully point to the fact that since no one has a clue what inflation rates will be in the long-run, longer-dated inflation expectations are a measure of confidence in the Fed rather than an actual measure of inflation expectations.

Conversely, the doves point out that inflation expectations of 3% per annum on average only means elevated inflation in the short-run, then back to ‘normal’ in the out-years.

Personally, I consider both the hawkish and dovish scenarios plausible, with some big caveats. What the doves miss is that, just because the wheels haven’t fallen off, doesn’t mean there isn’t a reason for concern. Of course, the market reflects that the Fed will get inflation back under control – otherwise, market measures would be very different. However, former Bank of England Governor Mervyn King has suggested it would be helpful for central banks to pursue policies that will contain inflation directly rather than rely on the public’s confidence in central banks’ ability to contain inflation as a matter of policy. The latter risks an unstable dynamic.

Incidentally, at the conference, St. Louis Fed’s Jim Bullard showed that, even with a most benign Taylor rule (John Taylor, co-organizer of the conference, is known for the so-called Taylor rule, a simple formula that suggests where interest rates ought to be), the Fed is significantly “behind the curve.” He then adds that if one doesn’t look at the current Fed funds rate, but what the market prices in over the next two years (i.e., the 2-year yield), the Fed is only a little bit behind the curve.

The latter is what got me worried. It wasn’t just Bullard, but it appears to me that the doves – and those are the ones in charge at the Fed – are perfectly content that the market is pricing in that things will be tighter 2 years out. That market-induced tightening, they argue, is sufficient to get inflation back down.

This “2 years out” theory has the hallmarks of “transitory” – it suggests that inflation surged temporarily, but all will be good down the road if we just keep steady.

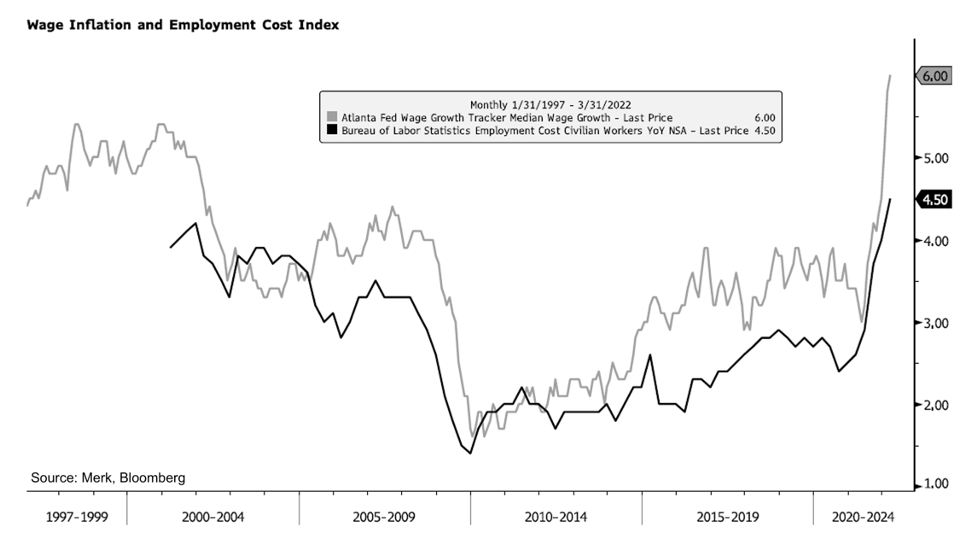

It is of course correct that the market has priced in additional rate hikes and tightening – hence higher 2-year rates. However, they seem to ignore what’s in plain sight and what Larry Summers has warned about: we have twice as many job openings as job seekers. This risks an inflationary spiral as high wage demands lead, at least in part, to broader inflationary pressures.

And there’s of course concern that we not going back to normal. 30% of the world’s grain production is offline which may well cause political instability in parts of the world, to name but one of the more apparent geopolitical risks. Of course, we don’t know whether this matters to the U.S., but the question is whether to ignore inflation risks emanating from crises around the world, even as they have already contributed to inflationary pressures.

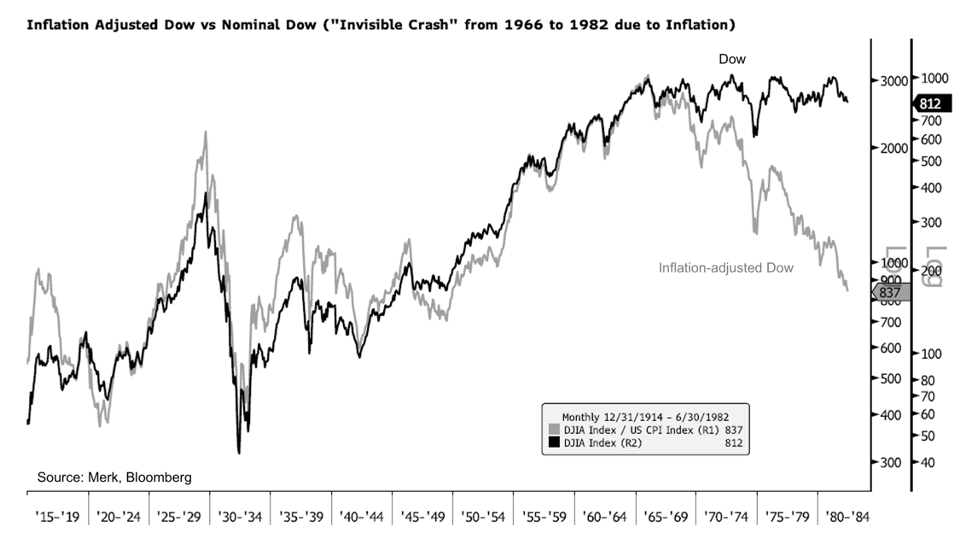

The risk, in my assessment, is that we unleash unstable dynamics. Recent market volatility is no coincidence. An overly accommodative policy may need to be supplemented by a rather tight policy; and, in turn, a U-turn in policy may again be in order. In market terms, let’s look at what happened last time inflation was a party pooper – the 1970s. The chart below shows the Dow Jones Industrial Average through the summer of 1982 when Volcker “won” the fight against inflation (for the time being) in black – and then the same Dow adjusted for inflation in grey:

I choose the Dow because of its long history; dividends are not reflected in the chart.

Once unstable dynamics are unleashed, all bets are off as to where the chips will fall. Back to the title of this analysis, the risk of stagflation could increase because the Fed may need to induce a recession, but might be unable to contain inflation.