Are Cryptocurrencies A Systemic Risk To The Global Financial Markets?

The self-described "thought experiment" delved into the links between the traditional world of mainstream finance and the rapidly emerging world of cryptocurrencies at the center of the "decentralized finance" movement.

TheDigitalArtist / Pixabay

Systemic risk is one of those phrases thrown around frequently but rarely defined. Those of us who have lived through it know it when we see it, but here's the CFA Institute's official definition...

SYSTEMIC RISK REFERS TO THE RISK OF A BREAKDOWN OF AN ENTIRE SYSTEM RATHER THAN SIMPLY THE FAILURE OF INDIVIDUAL PARTS. IN A FINANCIAL CONTEXT, IF DENOTES THE RISK OF A CASCADING FAILURE IN THE FINANCIAL SECTOR, CAUSED BY LINKAGES WITHIN THE FINANCIAL SYSTEM, RESULTING IN A SEVERE ECONOMIC DOWNTURN.

Systemic risk is therefore a finance-specific phrase to describe the butterfly effect, where a seemingly isolated or small event can have a cascading, exponential impact.

We all saw systemic risk play out as the housing crisis in the U.S. spread into a global contagion in 2008. Mortgage brokers in hot housing markets got financially unsophisticated people into loans they couldn't afford and later defaulted on, causing the mortgage market to melt down, ultimately toppling big financial institutions like Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns in the process.

Bad mortgages damaged U.S. bank balance sheets, so the credit markets seized up, leading to companies being unable to refinance debt coming due... and boom, bankruptcies. Some financial institutions failed to make good on obligations... and their trading partners in turn defaulted on their obligations to yet another counterparty.

The path from a homeowner defaulting on a $200,000 mortgage loan in Las Vegas to the nation of Greece defaulting on its debt is hardly a straight line... but these events aren't entirely disconnected, either.

Economic Policymakers Are Consumed With Minimizing Systemic Risk...

They want to keep financial blow-ups isolated to avoid future financial crises and the economic downturns, corporate failures, and loss of household wealth that go with them.

This is why regulators monitor bank balance sheets so closely... because the failure of a leveraged, global financial institution whose counterparties are other leveraged, global financial institutions is like a fast pass to a financial crisis.

We've had some severe dislocations in the markets this year... but they have thankfully remained isolated...

Global investment bank Credit Suisse took a stunning $5.5 billion loss as a counterparty to the failed Archegos Capital Management. Clearly their internal risk management systems failed, but the capital requirements imposed on them by regulators – in conjunction with a healthy debt market that allowed Credit Suisse to sell $3.75 billion in bonds yesterday to shore up its balance sheet – meant that Credit Suisse's problems wouldn't spread.

The system worked... systemic risk was averted through a combination of regulated capital requirements, other big banks having better internal risk controls than Credit Suisse, and the bond market being very accessible, which is itself the result of the economic policy of aggressively low interest rates.

Bitcoin Actually Made Its Debut In January 2009 During The Peak Of The Global Financial Crisis...

Absent the severe – but brief – sell-off last spring when the COVID-19 crisis began, markets have generally been rising and healthy during the entire rise of cryptocurrencies as an asset class.

So the Economist's question about the risk cryptocurrencies pose to mainstream finance is valid, especially given how volatile they have been this year.

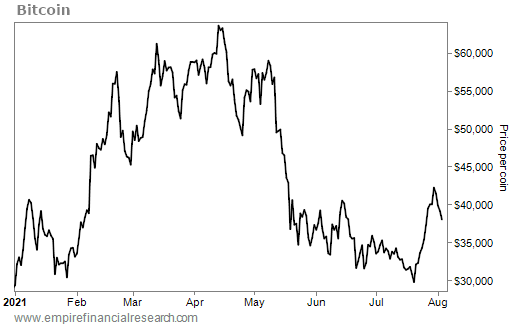

After peaking in April over $63,000, bitcoin fell over 50% and briefly dropped below $30,000 on July 20 – only to rise nearly 40% over the next 11 days...

It's been a wild ride for bitcoin this year... and other cryptocurrencies out there have been even more volatile.

As the Economist points out, the combined market cap for cryptocurrencies as an asset class has exploded recently. Over the last year, the combined crypto market cap has spiked from $330 billion to $1.6 trillion. The number of people holding this asset class has exploded too, with about 100 million digital wallets now holding crypto, three times more than in 2018.

Gone Are The Days Of Early Adopter Evangelists Dominating Cryptocurrencies...

When I spoke at a blockchain conference in fall 2018, I had to explain cryptocurrency and blockchain to my family and friends. The conference was mostly attended by diehard crypto evangelists, which is what I call the folks who believe that cryptos will eventually replace fiat currencies like the U.S. dollar.

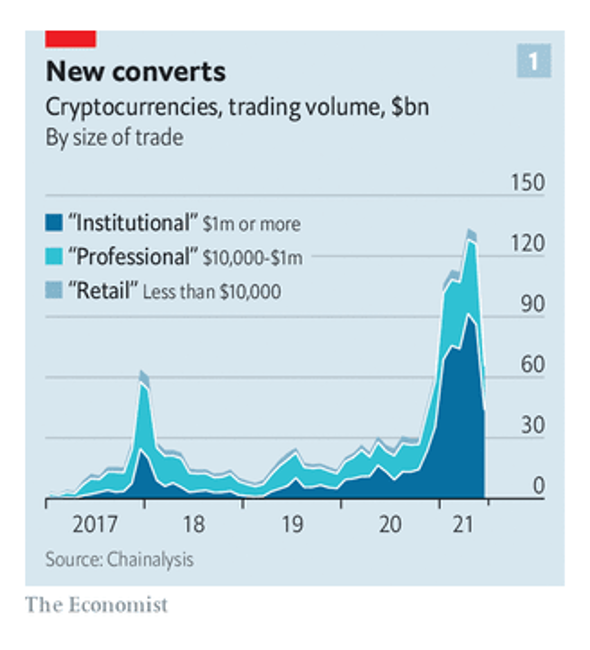

Fast-forward to today and the asset class has been institutionalized, with 63% of cryptocurrency trading dominated by institutions. The rest is dominated by professional traders, as you can see in the chart below...

Source: The Economist

What's amazing is that back in 2017, institutions comprised just 10% of cryptocurrency trades.

With So Many More Institutions – The Ones With All The Counterparties And Interconnectivity – Playing In Crypto Now, What Happens If We Get A Crypto Crash?

While bitcoin going to zero is an extremely low-probability scenario, trying to figure out what would happen if a technical failure, hacked exchange, or sudden regulatory action pushed it there makes for a good theoretical stress test.

A bitcoin crash would likely drag down other cryptocurrencies with it and destroy large amounts of wealth... although interestingly, most of the unrealized gains in crypto sit with the early evangelists, who have held it for more than a year and are probably the least likely to sell...

Source: The Economist

The biggest losses would therefore accrue to the latecomers (i.e., the institutions).

Not only is $1.6 trillion tied up in cryptocurrency assets, but other crypto-adjacent businesses would see their value plummet if bitcoin crashed, too. "Picks and shovels" crypto firms – like exchanges, both public and private – represent more than $100 billion in additional value. That doesn't even count the value embedded in companies like e-payments giant PayPal (PYPL) or financial services provider Visa (V), both of which play in crypto.

Adding up the dollars involved in the crypto economy – from cryptocurrencies themselves to crypto infrastructure – probably gets you to $2 trillion. This is a significant sum, and enough to do a lot of potential damage. For context, the International Monetary Fund estimate for toxic assets on bank balance sheets from 2007 to 2009 stands at just $1 trillion.

But the risk cryptos pose is greatly diminished by the fact that big banks don't own them. The bank regulatory capital requirement for crypto is 100%, which makes cryptocurrency an unattractive asset class to a financial institution whose business model depends on levering up its balance sheet.

As With Most Exercises In Theoretical Risk Assessment, The Key Question To Answer Is How Much Leverage Is Employed In The Crypto Ecosystem...

The way a blow-up becomes systemic is when investors use borrowed money to buy Asset A, the value of Asset A falls, and the lender makes a margin call. With Asset A having dropped so much, the investor sells Assets B, C, and D to make the margin call driven by Asset A's drop, but Assets B, C, and D will drop, too, if enough people sell them at once. This is where the contagion happens.

Unfortunately, it's tough to measure the amount of leverage in the system because the exchanges that traffic in the swaps that institutions use to trade crypto are all unregulated.

The other place contagions could creep in is with "stablecoins," which traders use to transact in bitcoin quickly and effortlessly. Stablecoins – such as Tether – are a $100 billion asset class and are pegged to the dollar or other fiat currencies.

The peg to the dollar means that stablecoins hold dollar-denominated assets, which is another place decentralized finance very much touches traditional finance. As the Economist explains...

ISSUERS BACK THEIR STABLECOINS WITH PILES OF ASSETS, RATHER LIKE MONEY-MARKET FUNDS. BUT THESE ARE NOT SOLELY, OR EVEN MAINLY, HELD IN CASH.

TETHER, FOR INSTANCE, SAYS 50% OF ITS ASSETS WERE HELD IN COMMERCIAL PAPER, 12% IN SECURED LOANS AND 10% IN CORPORATE BONDS, FUNDS AND PRECIOUS METALS AT THE END OF MARCH.

A CRYPTOCRASH COULD LEAD TO A RUN ON STABLECOINS, FORCING ISSUERS TO DUMP THEIR ASSETS TO MAKE REDEMPTIONS. IN JULY, FITCH, A RATING AGENCY, WARNED THAT A SUDDEN MASS REDEMPTION OF TETHERS COULD "AFFECT THE STABILITY OF SHORT-TERM CREDIT MARKETS."

Those with long-memories will recall disruptions in the commercial paper market during the global financial crisis wrecking all kinds of havoc in the real economy. Functioning short-term credit markets are crucial to the day-to-day functioning of the real economy of companies that make things and pay employees, as well as to Wall Street.

It's Enough To Lose Sleep Over, Until You Remember This A Theoretical Exercise...

Asking what would happen with bitcoin at $0 when it is trading at $38,000 is akin to asking what would happen if Internet titan giant Amazon (AMZN) went bankrupt tomorrow without warning.

Bitcoin zero is an extreme scenario that could only happen with sudden, coordinated regulatory action across a number of major countries... and it's pretty clear that finding out what would happen if bitcoin went to zero overnight is not the kind of economic experiment that any government official would want to attempt. Policymakers spend their time trying to avoid system failure... not induce it.

But it's clear the worlds of centralized and decentralized finance are firmly overlapping... which means both systems present systemic risk to each other.

It's hard not to imagine more regulation of cryptocurrency exchanges coming down the pike in the near future.

In The Mailbag, A Reader Responds To My Question About Whether We Should Change The Tax Code...

Hi Berna, the taxation of the wealthy is a very tricky area. Capital gains have historically been taxed at lower rates than ordinary income primarily because Governments have wanted to encourage capital formation and also because all business income is already taxed, so capital gains taxes are a kind of double tax. The issue of fairness cannot be easily answered.

"The theoretically correct answer is that capital gains taxes should probably be set at the level that raises the most revenue, since that is why taxies are levied! That, of course, argues for lower rates because high rates deter investors from realizing gains and deter investment. But then the differential between capital gains taxes and ordinary income taxes becomes contentious since it is the wealthy (and especially the ultra-wealthy) who accrue most capital gains.

"If capital gains taxes were doubled (to equalize them with ordinary income) as Biden has proposed, there will likely be two results. First there will be less capital formation as the returns for the risk investors take will be very significantly lowered. The second outcome will be that investors will defer realizing gains for as long as possible. The very likely outcome will be less tax revenue!

"One way to raise more capital gains tax is to eliminate the step-up of basis at death, so all capital gains will be taxed at death. This seems entirely fair, but the counter argument is that the wealthy pay 40% of their wealth in inheritance taxes, so the step-up in basis was always considered a quid pro quo for the 40% inheritance tax. I would therefore argue that if capital gains are taxed at death, the inheritance tax should be lowered somewhat to compensate for the change, though not a single Democrat would vote for that!

"Some progressives have argued that the solution is to tax unrealized capital gains annually. This is a disastrous idea for many reasons: Private companies and real estate would need to be appraised annually, which is both a time consuming, expensive, and highly subjective process. Even more problematically, owners of private companies, real estate, and farms would have to find the cash to pay the tax even though they hadn't sold any of the asset. This would include employees of startups whose shares can become very valuable long before the company goes public.

"So, we are left with deciding how much of an increase in capital gains taxes will actually raise more revenue without deterring investment. Some have suggested around 28%, which is what the tax was for many years, although even 28% is 5% higher than the OECD [Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development] average (23%) today (and if you add in the 3.8% Obamacare surcharge, U.S. capital gains taxes are already slightly above the OECD average!). I think there is a good argument to eliminate the step-up in basis at death, but the level of inheritance tax really should be lowered if this is done, otherwise wealthy taxpayers could be paying 60% or more of their estates in tax, which strikes me as unduly onerous.

"Lastly, I believe that if a wealthy person gives their money to charity, they should not pay capital gains tax on any gain, as effectively, the money they made was given back to society and not retained by the individual. I don't see charitable giving as tax avoidance at all.

"This is why capital gains taxes are so complex. They absolutely affect the level of capital formation and thus the growth of the economy and should be altered only after considerable thought and discussion." – Simon J.

Berna comment: Thanks for your thoughtful insights, Simon. There are no easy answers here.

I do think that a step-up of basis and taxation at death as you suggest could be problematic when the passed asset is an operating business, farm, or something else that you can't sell just a piece of to pay the tax.

I agree that taxing unrealized increases in wealth is subjective, complicated, potentially expensive, and leads to liquidity issues when the asset isn't liquid or easily divided into pieces.

But it's also a problem when the ultra-wealthy perpetually defer selling liquid stock holdings and realizing gains because banks will loan them cash if they post their liquid securities as collateral. They are effectively monetizing their assets and spending the money without realizing the gain – but it's a synthetic way to avoid taxes.

It's all so tricky.

Disclaimer: This article is not an investment recommendation, Please see our disclaimer - Get our 10 ...

more

Even Janet Yellen aid no systemic risk