A Rosie Forecast, And More

World economic growth is slowing. That’s so obvious, very few will disagree. I suppose there are people out there predicting imminent 1990's-like expansion, but they are few and far between. If recession begins soon, it will be the most anticipated one in history.

This was a prime question at my Strategic Investment Conference, which began this week and is ongoing. And the answer, sadly, is that even break-even growth will probably be elusive in the next year or two. Some experts I deeply respect think tougher times are coming, and soon. Most of the SIC speakers anticipate a recession, though one well-known economist/analyst thinks the US will avoid it.

I happen to think we will see boom times again, but not just yet, and maybe not even this decade, though that is a long time to forecast with any degree of confidence. Not only the US but much of the developed world has to face some other issues first.

Today and over the next few weeks I’ll share some highlights from the SIC. Please note, however, you don’t have to wait. You can join us right now and immediately watch video for the sessions you missed, plus get two more days of live expert analysis and our always-explosive closing panel.

Recession Imminent

We’ve been doing these conferences long enough (this is our 19th consecutive year) to have formed some traditions. One of the best is having David Rosenberg as the “lead-off hitter.” He hits it out of the park every time with an epic slideshow and specific forecasts that aren’t always pleasant but are usually right.

Two years ago, David (Rosie to his friends) was one of the top voices saying any post-COVID-19 inflationary boom would be temporary and short-lived. Unlike some of us, he never sold his “Team Transitory” t-shirt. At SIC this week, he explained why he thinks inflation will keep fading and recession is imminent—and maybe already here.

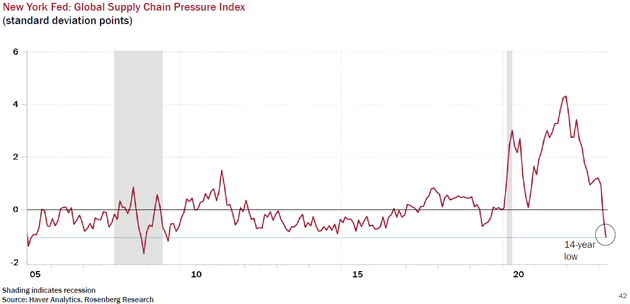

In Rosie’s view, the inflation we’ve seen was always about supply problems, not reduced demand. Here’s one of several charts he showed on that point. This is an index measuring supply chain stress—how long deliveries take and so forth. It rose very high in 2021 as relaxed COVID-19 restrictions unleashed pent-up demand, then fell sharply and is now below the pre-COVID-19 level.

Source: Rosenberg Research

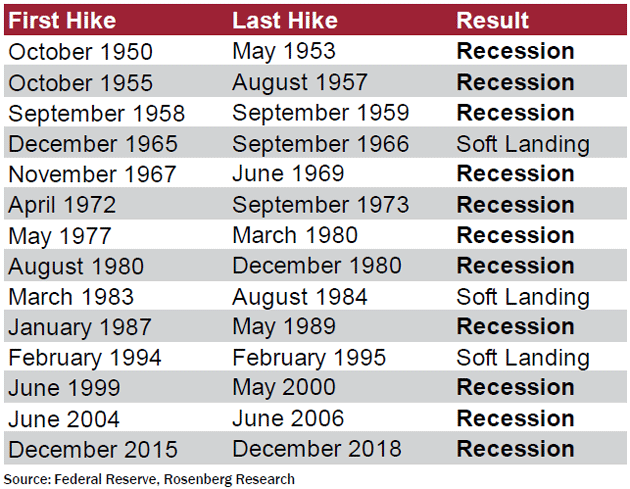

The Federal Reserve (and other central banks) responded to that 2021 spike only after a long delay. The Fed’s tools work by tightening access to credit, which reduces demand and eventually brings down prices. That’s the theory, at least. It was never going to work well in this supply-driven situation. Rosie thinks the inflation will stabilize on its own and the Fed’s tightening will serve mainly to spark a recession, as 11 of the last 14 tightening cycles did.

Source: Rosenberg Research

In fairness to the Fed, Rosie noted soft landings aren’t impossible. They have happened before, though not recently and not after the kind of aggressive rate hikes of the last year.

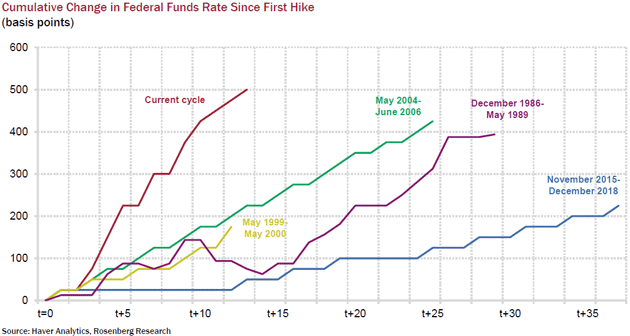

This is something I think many don’t grasp. The Fed raised rates far faster than it has in previous cycles. The speed is astonishing: This is a monetary policy shock unlike anything we have ever experienced. Here’s a chart with historical comparisons.

Source: Rosenberg Research

Those 75-basis-point hikes produced a far steeper trajectory this time. That wasn’t entirely crazy as:

- Fed officials were way behind the curve, as they should have been raising rates in early 2021. I have written about their excuses for this in several letters, but at the end of the day, that's all they have left: excuses.

- Given they were also seeing far steeper inflation readings than their models anticipated, it is not at all clear their policy is what brought inflation back down to the current (still-elevated) level. Rosie thinks it would have fallen anyway as supply problems eased. If so, the Fed may have pushed the economy into recession a lot sooner than it had to.

From there, Rosie went on to show how the rate hikes are already causing big problems. They began, as you would expect, with the most leveraged consumer purchases: vehicles and homes. Higher interest rates generally make those goods less affordable and, as sales dwindle, reduce employment in those sectors.

More dominoes fall and usually recession follows. In this case, low unemployment and rising wages are slowing the process but it is still happening.

Concurrently, the rising interest rates and flat/inverted yield curve make banks less profitable, so they reduce their lending activity. We’ve already seen bank failures, and more are probably coming. This tightens credit even more.

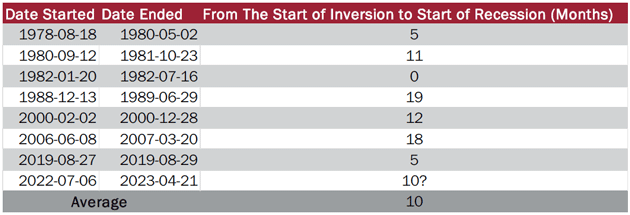

And speaking of the yield curve, I’ve often described it as a reliable but early recession indicator. Rosie had a slide on that point. Looking at the 2-year and 10-year Treasury curve, he calculated the time until the last 7 recessions began. The average wait was 10 months. That means we are entering the zone this month. The longest delay was 19 months.

So, unless the yield curve is wrong this time, recession will probably begin sometime this year, and could already be underway—recessions are typically identified in hindsight. Minor amusing point: Many so-called “blue chip economists” continue to deny recession probabilities almost until we are completely through them. So much for their models.

Source: Rosenberg Research

Then what? Rosie thinks this week’s rate hike will be the last and the Fed will begin cutting rates soon. He says 500 basis points won’t surprise him and would be typical based on past recessions. I realize that’s hard to imagine right now. A return to near-zero rates is certainly quite different from my own thinking. But I’ve learned not to discount Rosie’s forecasts. They are often “out of consensus” but the consensus is often wrong, too.

I read Rosie almost every day. He excels at seeing the right direction if not the actual destination. Will the Fed eventually cut rates? Absolutely. Will it be 500 basis points? I don't think so but it'll be closer to that than 50 basis points.

Rosie went on to talk about what this will mean for the stock and bond markets. I won’t share that here, but you can register and watch his whole presentation.

Pushing on Strings

Another longtime SIC fixture is Lacy Hunt, chief economist at Hoisington Investment Management. His outlook is more long-term than Rosie’s but consistent with it. You can look at Lacy’s presentation as the theoretical basis for the patterns Rosie describes. None of this is accidental or random. It happens for specific reasons, which Lacy outlined clearly and eloquently.

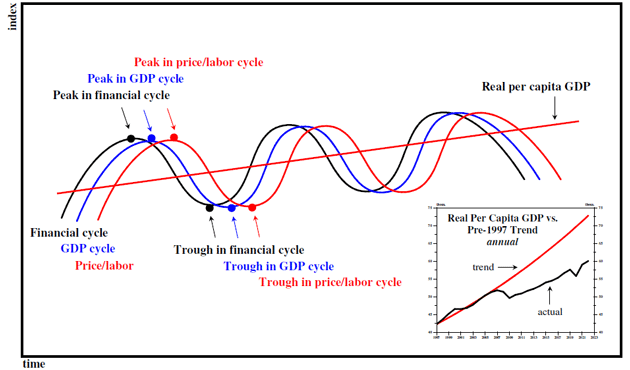

In Lacy’s view, the “business cycle” we discuss is actually three different waves occurring in a specific order. The financial cycle comes first, followed by a GDP cycle, and then a price/labor cycle. They peak and trough in that sequence. He illustrated it with this graph showing how one wave leads to another.

Source: Hoisington Investment Management

The financial cycle comes first, with monetary policy heavily influencing its movement. Loose credit unleashes both inflation and excessive risk-taking. These push GDP up and, later, make wages and prices rise. Then the financial cycle peaks, falls, and the others fall as well.

Again, this isn’t new. Lacy talked about the long history of economists going back to David Hume in 1752, all describing the same basic process. Each generation gained a little more understanding of it.

Knut Wicksell first described the “natural rate of interest” concept in 1898. That is an interest rate that neither slows nor accelerates economic activity. In other words, it’s what we would have if central banks weren’t constantly interfering. (It is more complicated than that, as markets can temporarily get out of balance as well.)

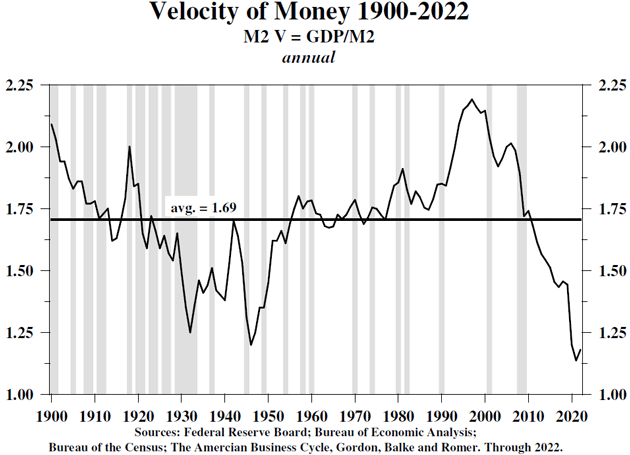

However good the intent of central banks, this activity is what causes booms and busts. Central banks can control the money supply, but the amount of money isn’t the only factor. The speed at which it moves through the economy (the “velocity of money”) matters, too. Creating more money has little effect if people don’t use it.

As Lacy’s chart shows, velocity right now is even lower than it was in the Great Depression. I have been following Lacy for almost two decades and we have become close friends. Lacy was predicting the velocity of money would slow to this level well over 10 years ago from my memory. And probably before then. This is a serious problem for the Federal Reserve’s attempts to stimulate growth.

Source: Hoisington Investment Management

Note how velocity has actually been falling since the 1990's with only a few brief interruptions. The decline intensified in 2007‒2009 as the Fed fought the financial crisis with zero interest rates and quantitative easing. Then it fell even more vertically with the 2020 COVID-19 stimulus policies. Force-feeding liquidity into an economy without good uses for it doesn’t seem to work very well.

Lacy tracks this with what he calls the “marginal revenue product of debt.” That’s the amount of GDP growth generated by each additional dollar of debt. That has been falling for years and is set to fall even more as higher rates divert a bigger part of the revenue from debt-funded projects to interest payments instead of more productive uses.

Although I have been writing that I expect to see large US interest payments on the government debt, it still makes me shudder to see that interest payments on the US debt will be over $1 trillion. When interest payments are more than defense spending, something is radically out of balance.

The bottom line: Monetary policy is losing its ability to stimulate growth. We used to call this “pushing on a string,” but Lacy says that metaphor is no longer sufficient. Just as that cycle chart shows, this peak in the financial cycle will be followed by a peak in GDP growth, then peak wages and prices (i.e., inflation). We’re already past that point and it is downhill from here, consistent with the recession Rosie expects.

These are bleak outlooks even in today’s negative environment. Before you despair, let me remind you we will get through this. Not to say it will be easy, but we at least have the advantage of forewarning. We have time to prepare.

Trillion-Dollar Question

Kind of like Lacy’s cycle chart, I design the SIC agenda in a specific order. Each topic builds on those before it because I want attendees to consider the ideas in a logical way.

I put our energy panel on the first day because energy and economic growth are really two sides of the same coin. You can look at charts of global GDP growth and energy demand over the last 1,000 years and the lines are virtually indistinguishable. Abundant energy promotes growth while lack of energy inhibits it. Similarly, energy demand typically increases with economic growth.

While other technologies are advancing, for now the world energy supply still depends mostly on oil, natural gas, and coal. We saw last year how access to these can be interrupted with very little notice. And even without wars and sanctions, energy supply is lagging energy demand. That means higher prices and a drag on GDP growth.

Sometime soon, I'm planning a series of letters on energy and oil and gas. It really needs a deep dive. But let me summarize what the oil panel told us.

Demand for energy in the developing world is only going to increase. The IEA has already had to raise their demand forecasts three times in the last 12 months. And that is in the face of a global slowdown.

All the increased demand is coming from the developing world. The US, Europe, and the rest of the developed world have seen flat demand for decades even as we try to actually reduce demand. All of our efforts have simply flatlined demand, not reduced it.

The marginal growth in global oil and gas supply comes from the United States. And our production is flat because the large producers are not drilling in any size other than to replace their own falling production from their existing wells.

Energy panel member Josh Young noted:

“Scott Sheffield just announced he's retiring from Pioneer Natural Resources, a large leader in shale production in the US and in West Texas in particular. He talked about what it would take for Pioneer to start growing their production organically wasn't just a higher oil price, it was a higher stock price. And I think he was trying to change the understanding the way politicians and investors and others are looking at it. From his perspective, it's less about the single well returns or the capital returns on investment as much as it's also about the cost of capital. If his cost of capital is too high, he's better off buying back stock or returning capital.

"...And there's been a shift in capital allocation by oil and gas producers because of that sort of signal from the market to return capital.”

I have noted this in the past. If you spend $1 billion developing new reserves, and the market only rewards you with $700 million of increased market cap, you do what oil companies are doing now: replace your depleted production to maintain your share price. Or if you are Exxon Mobil, you try to buy Pioneer to get exposure to the Permian Basin

The oil panel was expectedly bullish, and I know some other speakers will talk about triple-digit oil. Some are outright forecasting $150 oil in 2024. So far, there has not been one discouraging note about commodities and especially the energy space. I've been doing this conference for 19 years and I don't ever remember that unanimity on the commodity space.

Now, what about energy in the kind of recession scenario Rosie and Lacy expect? This is truly a trillion-dollar question. It used to be predictable. Recessions meant less travel, less shipping, and generally lower energy demand which led to lower prices as demand dropped faster than supply. It is not at all clear the same pattern will hold this time.

What happens in a recession where energy prices go up, or at least hold steady? It starts to look more like “stagflation,” which is even less fun.

Last year I wrote a letter saying recession was likely, but it would be a weird one. I still think that’s right. Every recession is a little different, of course. I expect this one to be even more so because the economy has seen such extraordinary change—demographically, geopolitically, and technologically. Historical comparisons to the 1970's and before are less enlightening than they used to be. Even the 1990's were radically unlike what we face today.

When you’re flying blind, you have to rely on the instruments. My “instruments” are conveniently all in one (virtual) place at the SIC. I highly recommend you watch them closely.

More By This Author:

Still Rethinking The FedFrom Theory To Reality

Inflationary Choices