Yet, It Is Likely To Get Worse

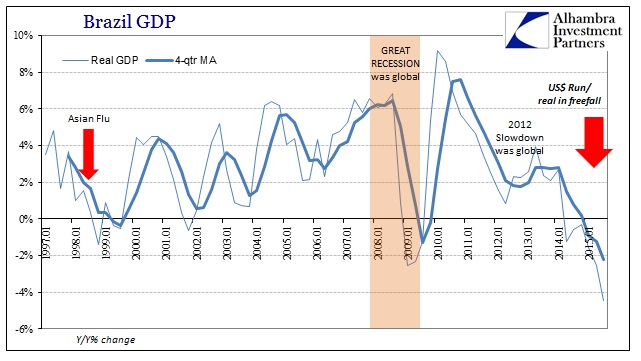

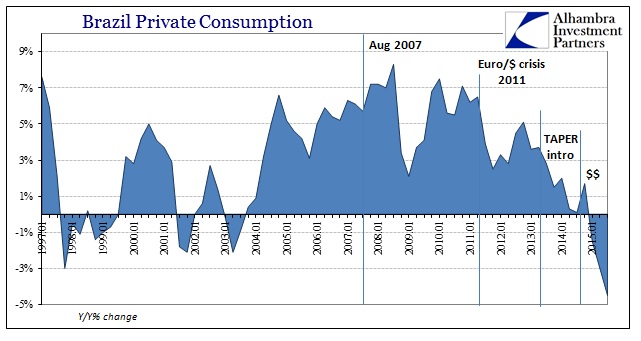

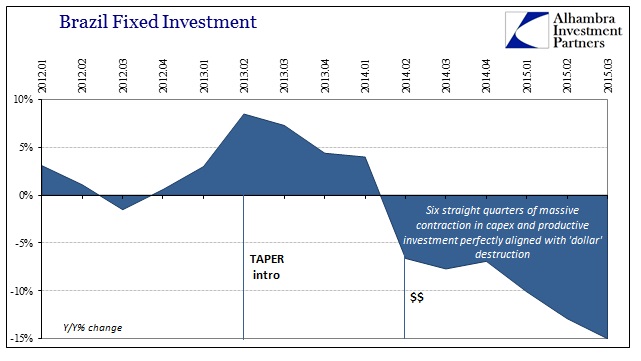

The GDP statistics for Brazil as of Q3 2015 were worse than expected in every way imaginable. Real GDP fell 4.5% Y/Y, which is nearly double the worst quarter Brazil experienced during the Great Recession. Household spending fell 1.7%, the third consecutive quarter of contraction, while fixed investment declined an astounding 15%. That was the sixth straight reduction and the third in a row worse than -10%. Private consumption fell by 4.5%, by far the worst since Brazil’s tumultuous 1990’s.

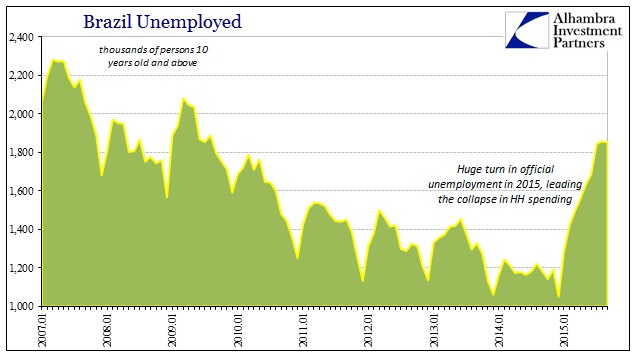

There was no silver lining anywhere, as the country struggles still with unmanageable imbalances. Unlike the Great Recession, this time the South American nation has seen (in official statistics) a surge even in the official count of unemployed. IBGE reported just 1.05 million unemployed at the end of 2014, but 1.85 million in September. That reverses a fifteen year trend that wasn’t much disturbed even by the Great Recession. In other words, if the ongoing dislocation is showing up even in the official rolls of the unemployed, and at an 80% increase, then the economic situation is beyond dire and threatening toward pure chaos.

That all of this would align so closely to the global eurodollar condition isn’t surprising, it is simple math. Brazil’s “prosperity” was founded on the same myth as China’s (and the US bubble conditions). It is difficult to parse what is organic “demand” and even “supply” in Brazil, meaning that there is no indication as to how far the system might have to just implode in order to unpack and separate its basic condition from the artificial introductions of “dollar” financialism. Like the rest of the world, Brazil is finding out the nature of the eurodollar on the downslope.

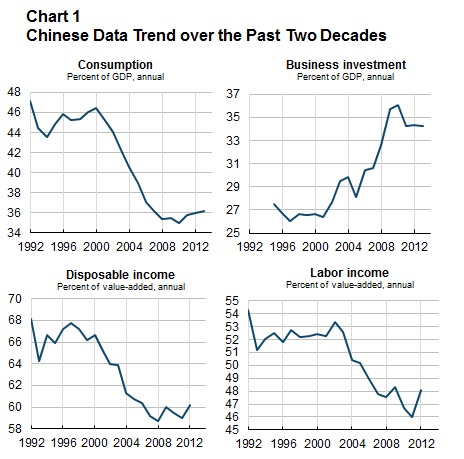

This is all just financialism stripped of ongoing monetary expansion; in this case, the wholesale “dollar” expansion that carried global and US growth (more in the former than the latter) for more than a decade. Brazil and China “emerged” in the 2000’s on that monetary influence, which is highly visible any place you actually look. The distortion in the Chinese economy is just as striking (data below taken from the Atlanta Fed).

The heavy surge of the “Golden Age” of the eurodollar is plainly apparent, as consumption dropped from 46% of GDP in China in 2000 to just 35% at the bottom of the Great Recession. That “investment” filtered out to the rest of the world as both global trade and co-locating financial expansion. That was all a lie, one driven by the interference of an unsustainable financial evolution that was treated as if it were actual, organic economic growth.

On this side of 2007, especially after 2011, banks just aren’t willing to press it all back into the same condition as pre-2008. Even though the eurodollar standard operates on wholesale principles, and thus offers a dark screen of complexity and technicality, it really is just basic monetarism – “money” supply increases, economy looks like it gains; “money” supply contracts, it looks like deflation and depression.

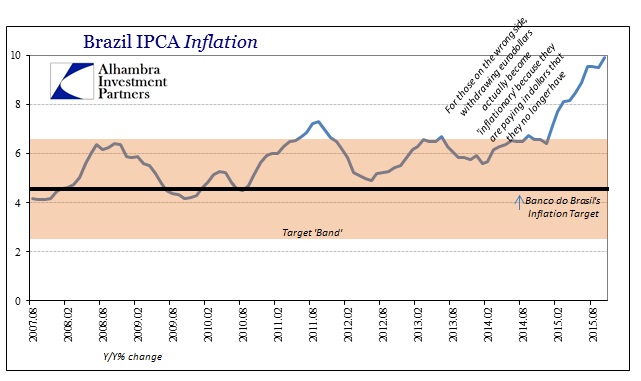

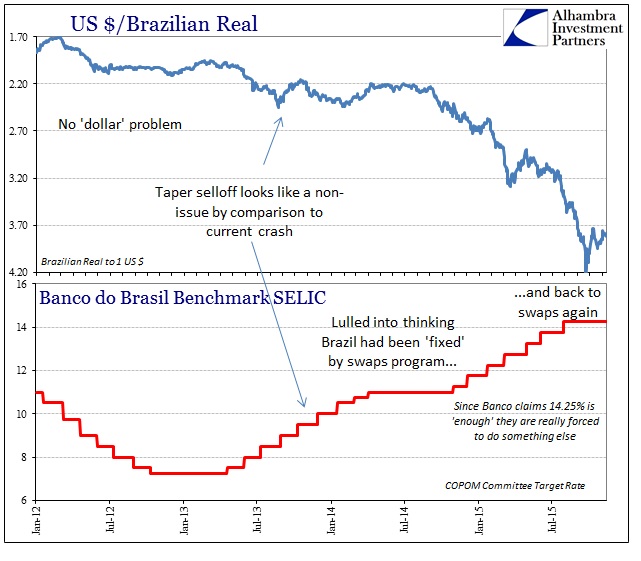

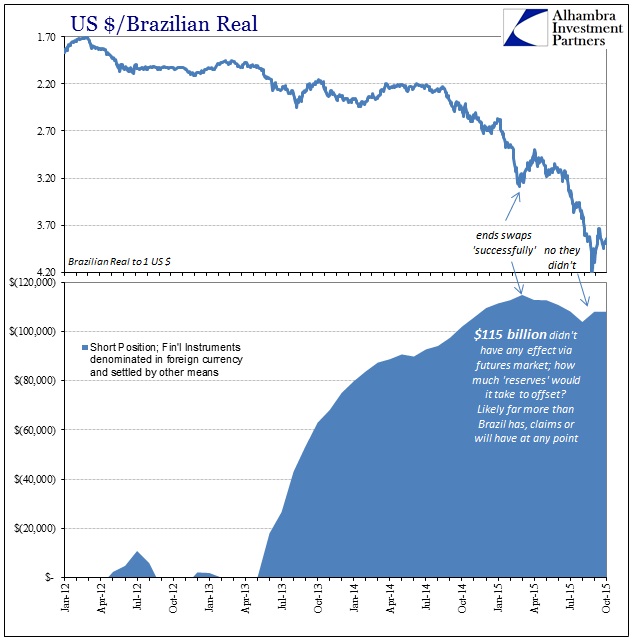

In Brazil’s case, it is the literal worst of that end of the global wholesale bargain; their “deflation”, being on the short of the wholesale “dollar”, actually produces increasingly runaway consumer prices as the belated cost of trying to use wholesale currency that is no longer available to it. Thus, the entire economy must “pay up” for the “privilege” of accessing the increasingly more difficult eurodollar network just to maintain the semblance of now past economic condition – and even that is increasingly expensive as the central bank is forced into greater and greater monetary despoliations just to keep it from plummeting even further out of hand.

Again, from that perspective it is nearly impossible to figure how much worse it might get. Like US consumer spending and the manufacturing recession, it has occurred already without the heaviest weight of countermeasures and the natural processes of imbalance. In Brazil, Banco do Brasil has already run its benchmark SELIC to 14.25%, burned up more than $110 billion in “swaps” (the wholesale problem), and still Brazil sees the real at nearly 4 rather than 2, inflation at more than 10% and the real economy, official employment with it, in absolute freefall. What will it be like if this all really gets serious? What we have seen so far of the eurodollar this year, apart from August, is just the potential first act; or, as I characterized it this morning, the end of the beginning.

I don’t want to minimize the dangerous condition of Brazil itself, but in many ways this is about more than just their tragic struggles. They are the leading edge of what happens when such finance and economy go into reverse. We saw this here in the US and the “developed” world only briefly in 2008 as the eurodollar in its first blink likewise just disappeared (only quickly and sharply) into the ether of modern banking. Thus, what Brazil represents is not just a reminder of that condition but rather proof that the same indiscretions and weaknesses that plagued the global economy then are still here and perhaps (likely?) even worse now (conditionally).

In 2009, at least, there was some glimmer of hope that the eurodollar/wholesale problem was just a temporary, cyclical interruption and that central bank coordination would fill in the gap until normal function was restored. By 2011, however, that possibility had turned to impossibility, proving quite definitively beyond any central bank, even the Fed’s, determined reach. We, with Brazil out in front, are dealing with the slow, almost methodical revelation and consequences of financialization in increasingly unalterable reverse.

Disclosure: None.