Supply, Demand And The Price Of Oil

A few weeks ago I offered some calculations suggesting that lower demand for oil might account for about $20/barrel of the dramatic decline in the price of oil since last summer. Here I point to some other evidence consistent with that conclusion.

Last week the IMF’s Rabah Arezki and Olivier Blanchard produced a very useful assessment of the role of supply and demand in the recent oil price decline. They note for example that the IEA’s current estimate of world oil demand growth for 2014:Q3 is 800,000 barrels/day below what the organization had been anticipating as of last June.

Source: IMFDirect.

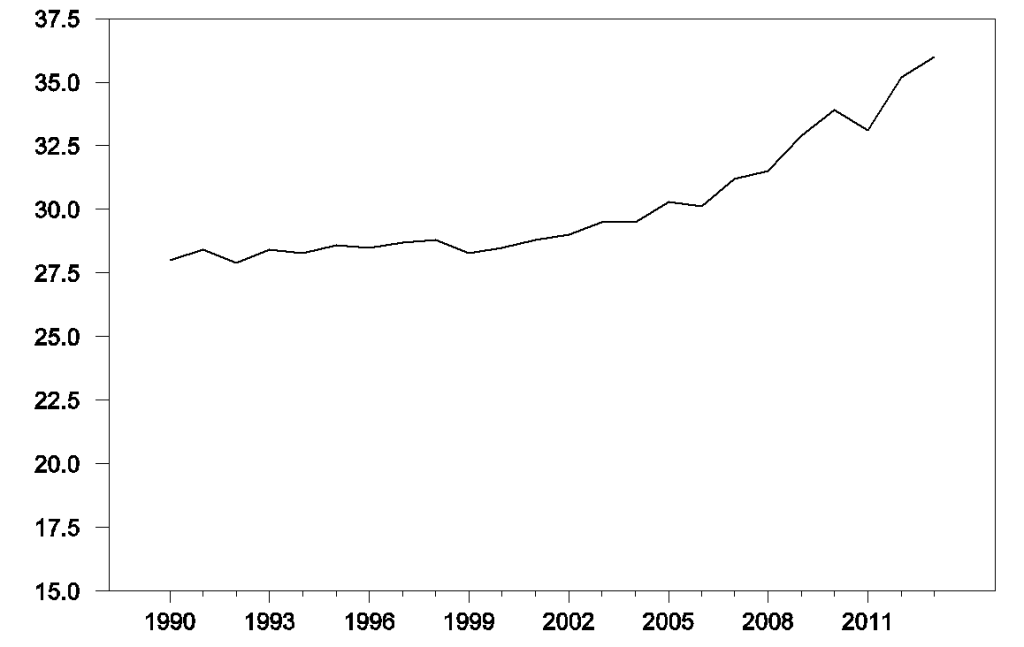

The suddenness of this shift suggests that economic weakness in Europe, Japan, and China made a contribution. In the case of the United States, some of the long-run demand response to the price run-up of the 2000s is still underway, as seen for example in the continuing improvements in fuel economy of new cars sold in the U.S.

Average fuel economy of new passenger vehicles in miles per gallon (from EIA).

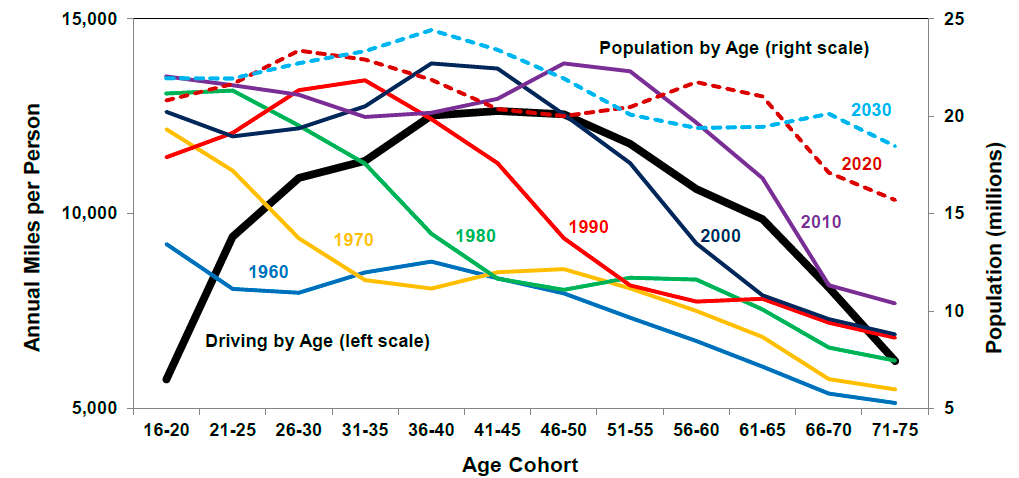

But Steve Kopits calls attention to Don Pickrell’s documentation of some important long-term trends in U.S. demand as well. The American population is aging, and older people drive less.

Source: Pickrell (2014).

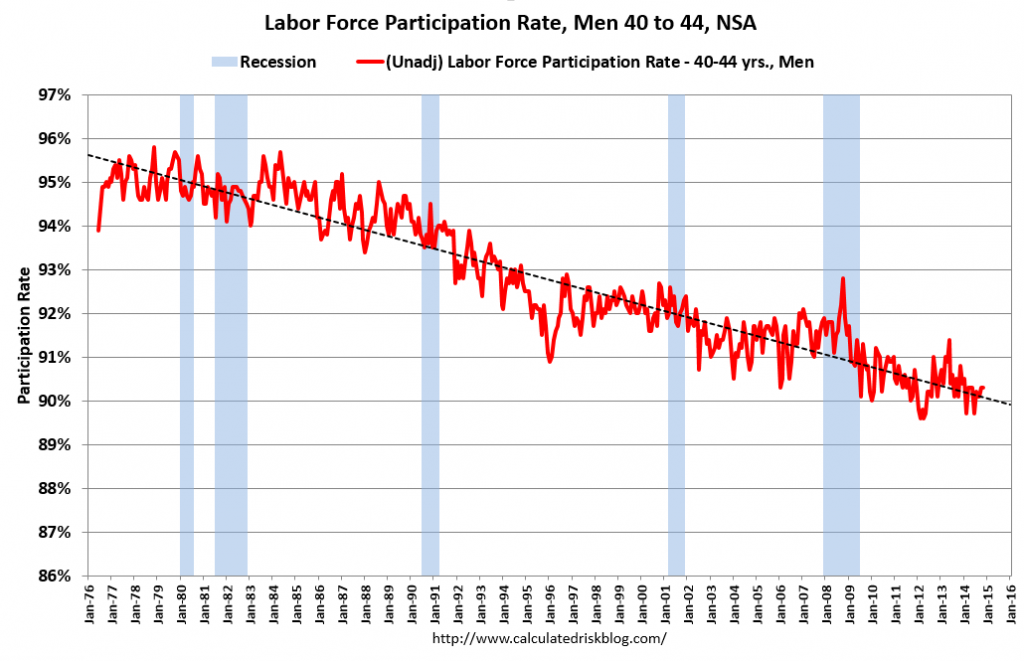

In addition, people who don’t have jobs don’t drive as much. Much of the decline in the U.S. labor force participation rate seems due to long-run developments that were in evidence well before the Great Recession.

Source: Calculated Risk.

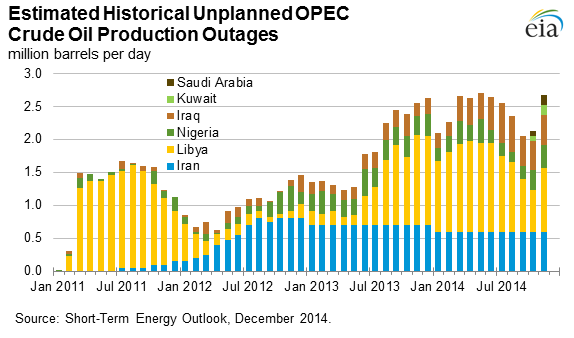

Another contributing factor to an excess supply of oil was a return of Libyan production between July and October. But the latest estimates are that some of this was lost again last month. And this weekend Libya’s largest oil port was attacked, raising the possibility that more of the country’s exports will again be disrupted.

Source: EIA.

But the biggest factor in producing an excess supply of oil has been the success of the U.S. shale oil production. U.S. inventories are well above what’s expected for this time of year.

Source: EIA.

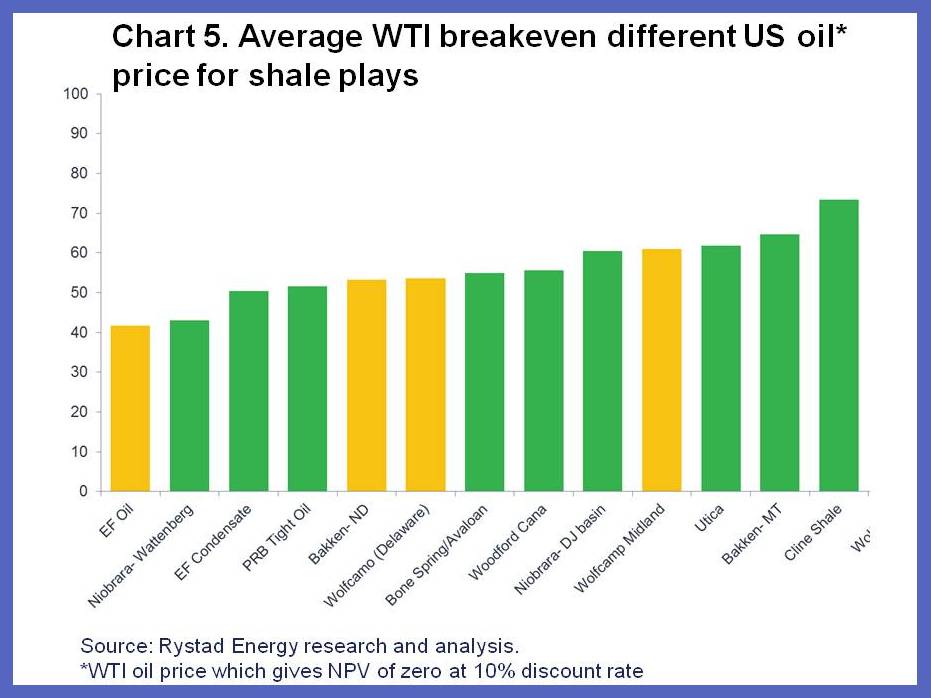

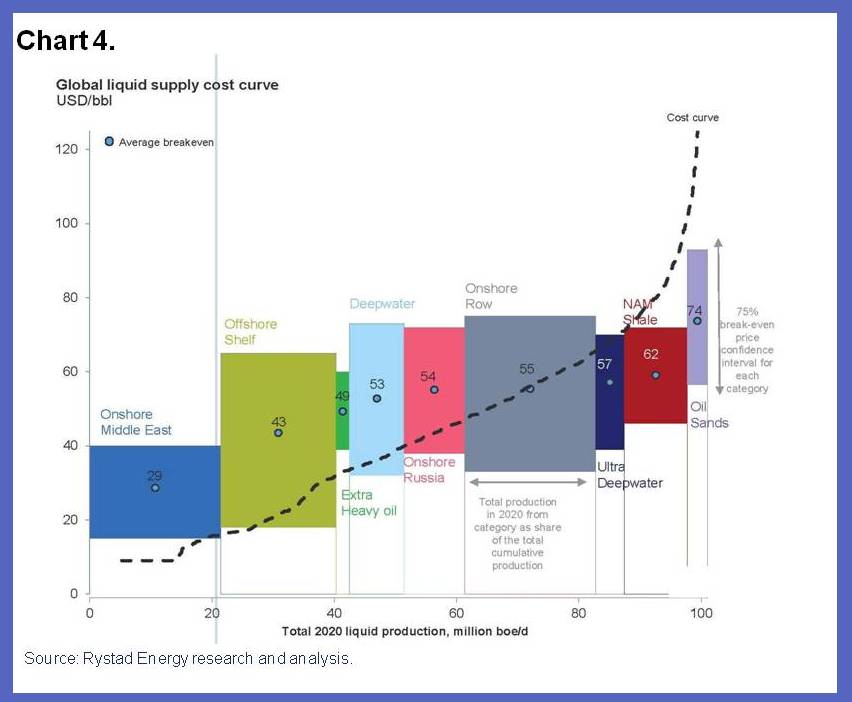

At what price would supply and demand be back in balance? I won’t even make an attempt to predict short-run developments for the wild cards like Libya, Iraq, and China. But in principle, the U.S. supply situation should be simpler. At current prices, some of the higher-cost producers will be forced out. It should be a textbook problem of finding the point on the marginal cost curve at which there’s an incentive for the marginal producer to meet desired demand; given a quantity Q demanded on the horizontal axis, find the price P associated with that Q from the height of the vertical axis on the marginal cost curve. The problem is, nobody knows for sure exactly what that marginal cost curve looks like, and sunk costs for existing wells make it hard (and painful for the oil producers) to find out.

Source: IMFDirect.

Longer term, I think we can anticipate ongoing geopolitical disruptions in Africa and the Middle East and a resumption of demand growth from emerging economies. That is why I believe that before long the world will once again want that higher-cost oil. But December 2014 doesn’t seem to be the time to try to sell it.

Source: IMFDirect.

Disclosure: None.