Oops! Low Oil Prices Are Related To A Debt Bubble: Part 2

<<Read More: Oops! Low Oil Prices Are Related To A Debt Bubble: Part 1

Much of this oil is non-conventional oil–oil that cannot be extracted using the inexpensive approaches we used in the early days of oil production. In some cases, non-conventional oil is so viscous it needs to be melted with steam, before it will flow freely. Some of the unconventional oil can only be extracted by “fracking.” Some of the unconventional oil is very deep under the ocean. Near Brazil, this oil is under a layer of salt. If prices would remain high enough, for long enough, we could get this oil out.

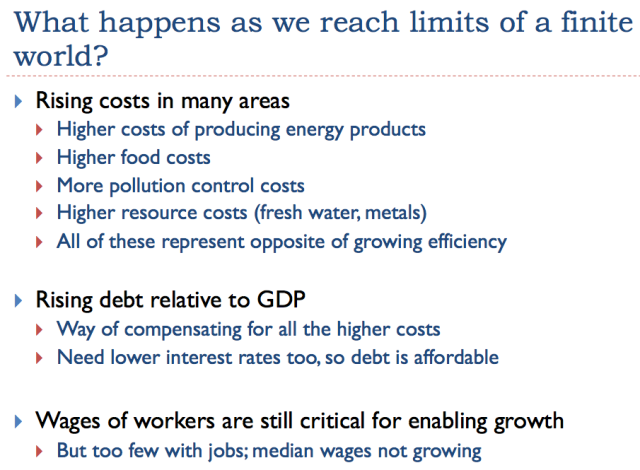

The problem is that in order to get this unconventional oil out, costs are higher. These higher costs are sometimes described as reflecting diminishing returns–more capital goods are needed, as are more resources and human labor, to produce additional barrels of oil. The situation is equivalent to the system of oil extraction becoming less and less efficient, because we need to add more steps to the operation, raising the cost of producing finished oil products. The higher price of oil products spills over to a higher cost for producing food, because oil is used in operating farm equipment and transporting food to market. The higher cost of oil also spills over to the cost of almost anything that is shipped long distance, because oil is used as a transportation fuel.

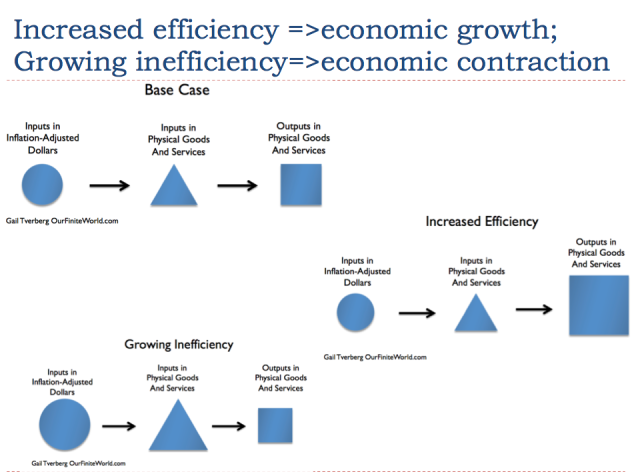

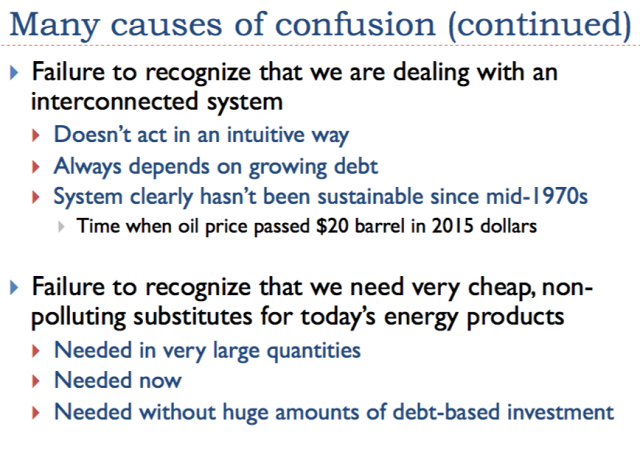

You will remember that increased efficiency is what makes an economy grow faster (Slide 7, also Slide 37). Diminishing returns is the opposite of increased efficiency, so it tends to push the economy toward contraction. We are running into many other forms of increased inefficiency. One such type of inefficiency involves adding devices to reduce pollution, for example in electricity production. Another type of inefficiency involves switching to higher-cost methods of generation, such as solar panels and offshore wind, to reduce pollution. No matter how beneficial these techniques may be from some perspectives, from the perspective of economic growth, they are a problem. They tend to make the economy grow more slowly, rather than faster.

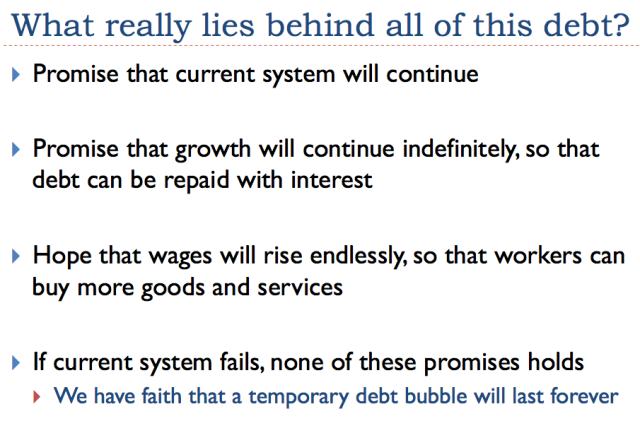

The standard workaround for slow economic growth is more debt. If the interest rate is low enough and the length of the loan is long enough, consumers can “sort of” afford increasingly expensive cars and homes. Young people with barely adequate high school grades can “sort of” afford higher education. With cheap debt, businesses can afford to buy back company stock, making reported earnings per share rise–even though after the buy-back, the actual investment used to generate future earnings is lower. With sufficient cheap debt, shale companies can create models showing that even if their cash flow is negative at $100 per barrel oil prices ($2 out for $1 in) and even more negative at $50 per barrel ($4 out for $1 in), somehow, the companies will be profitable in the very long run.

The technique of adding more debt doesn’t fix the underlying problem of growing inefficiency, instead of growing efficiency. Instead, as more debt is added, the additional debt becomes increasingly unproductive. It mostly provides a temporary cover-up for economic growth problems, rather than fixing them.

A common belief has been that as we reach limits of a finite world, oil prices and perhaps other prices will spike. In my view, this is a wrong understanding of how things work.

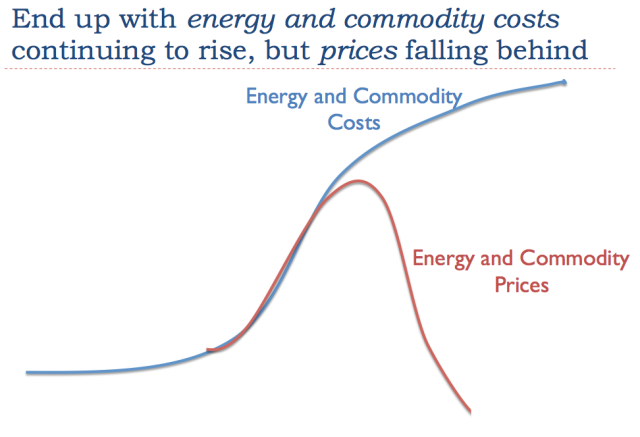

What we have is a combination of rising costs of production for many kinds of goods at the same time that wages are not rising very quickly.This problem can be temporarily hidden by a rising amount of debt at ever-lower interest rates, but this is not a long-term solution.

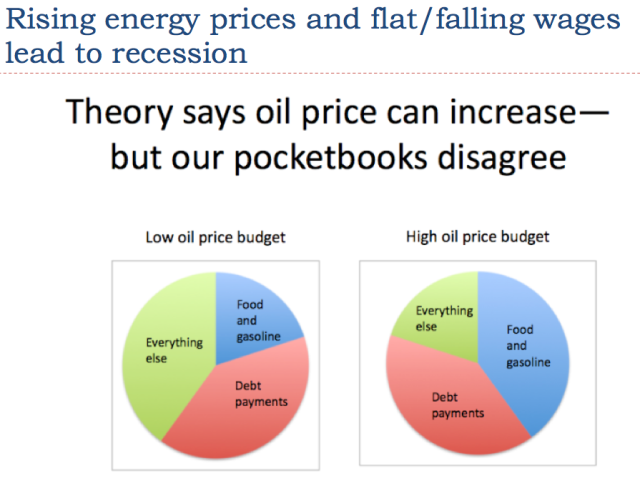

We end up with a conflict between the prices businesses need and the prices that workers can afford. For a while, this conflict can be resolved by a spike in prices, as we experienced in the 2005-2008 period. These spikes tend to lead to recession, for reasons shown on the next slide. Recession tends to lead to lower prices again.

The image on Slide 26 shows an exaggeration to make clear the shift that takes place, if the price of oil spikes. When the price of one necessary part of consumers’ budgets increases–namely the food and gasoline segment–there is a problem. Debt payments already committed to, such as those on homes and automobiles, remain constant. Consumers find that they must cut back on discretionary spending–in other words, “Everything else,” shown in green. This tends to lead to recession.

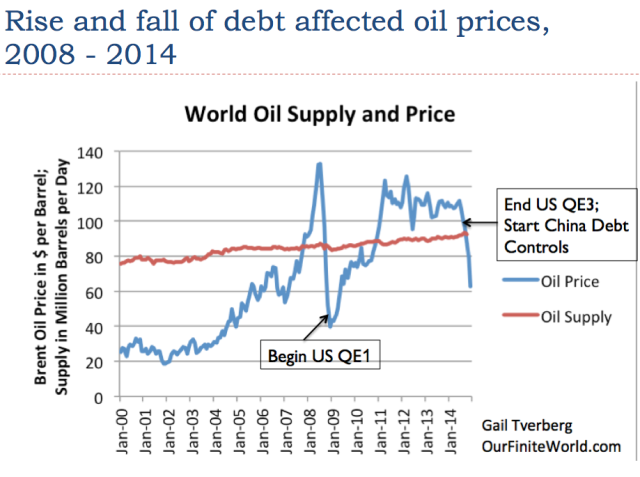

If we look at oil prices since 2000, we see that the period is marked by steep rises and falls in oil prices. In Slides 27 – 29, we will see that changes in the price of oil tend to correspond to changes in debt availability and cost.

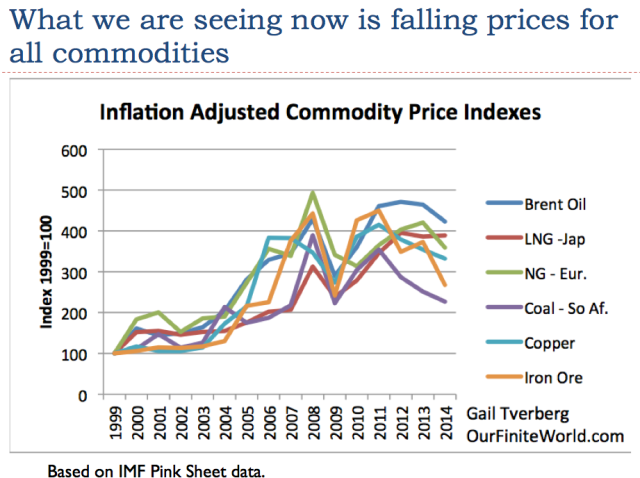

In 2008, oil prices rose to a peak in July, and then dropped precipitously to under $40 per barrel in December of the same year. Slide 27 shows that the United States began its program of Quantitative Easing (QE) in late 2008. This helped to lower interest rates, especially longer-term interest rates. China and a number of other countries also raised their debt levels during this period. We would expect greater debt and lower interest rates to increase demand for commodities, and thus raise their prices, and in fact, this is what happened between December 2008 and 2011.

The drop in prices in 2014 corresponds to the time that the US phased out its program of QE, and China cut back on debt availability. Here, the economy is encountering less cheap debt availability, and the impact is in the direction expected–a drop in prices.

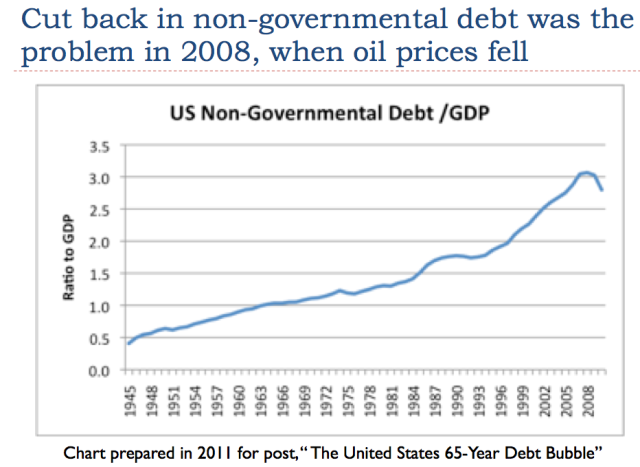

If we go back to the steep drop in oil prices in July 2008, we find that the timing of the drop in prices matches the timing when US non-governmental debt started falling. In my academic article, Oil Supply Limits and the Continuing Financial Crisis, I show that this drop in debt outstanding takes place for both mortgages and credit card debt.

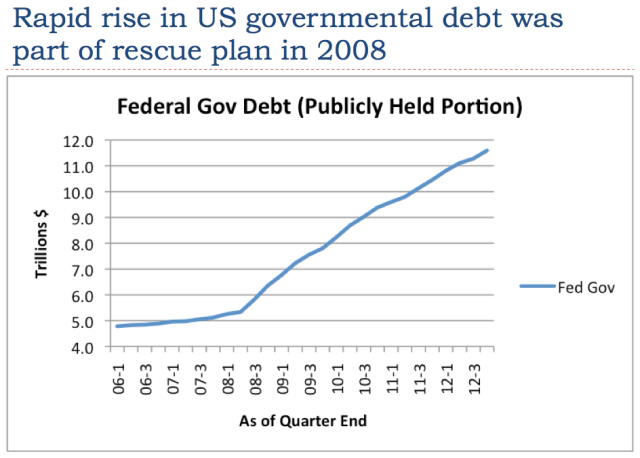

The US government, as well as other governments around the world, responded by sharply increasing their debt levels. This increase in governmental debt (known as sovereign debt) is part of what helped oil and other commodity prices to rise again after 2008.

We often hear about the drop in oil prices, but the drop in prices is far more widespread. Nearly all commodities have dropped in price since 2011. Today’s commodity price levels are below the cost of production for many producers, for all of these types of commodities. In fact, for oil, there is hardly any country that can produce at today’s price level, evenSaudi Arabia and Iraq, when needed tax levels by governments are considered as well.

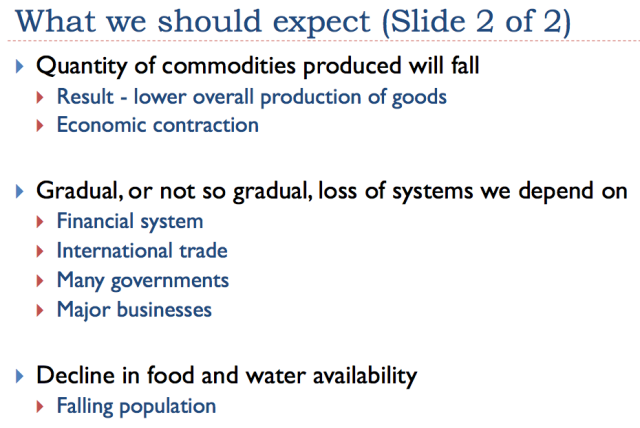

Producers don’t go out of business immediately. Instead, they tend to “hold on” as best they can, deferring new investment and trying to generate as much cash flow as possible. Because most of them have no alternative way of making a living, they often continue producing, as best they can, even with low prices, deferring the day of bankruptcy as long as possible. Thus, the glut of supply doesn’t go away quickly. Instead, low prices tend to get worse, and low prices tend to persist for a very long period.

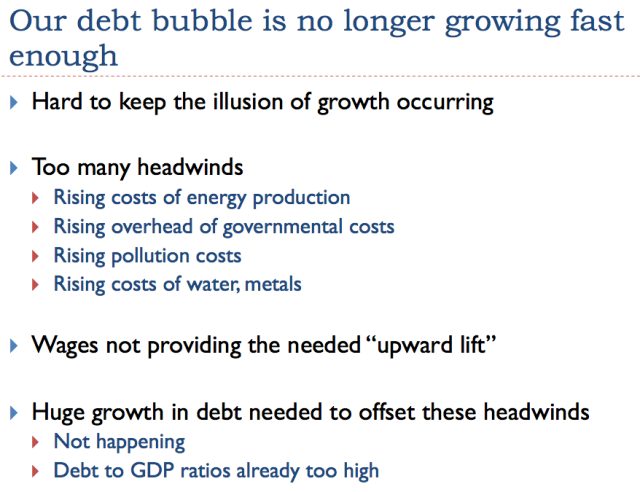

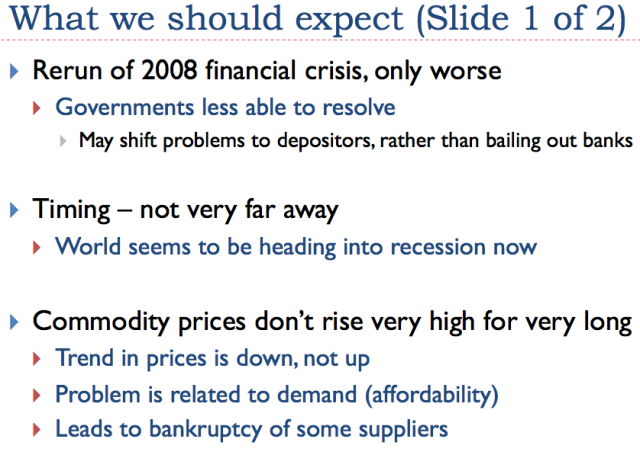

In 2008, we had an illustration of what can go wrong when the economy runs into too many headwinds. In that situation, the price of oil and other commodities dropped dramatically.

Now we have a somewhat different set of headwinds, but the impact is the same–the price of commodities has dropped dramatically. Wages are not rising much, so they are not providing the necessary uplift to the economy. Without wage growth, the only other approach to growing the economy is debt, but this reaches limits as well. See my post, Why We Have an Oversupply of Almost Everything (Oil, labor, capital, etc.)

There is some evidence that the Great Depression in the 1930s involved the collapse of a debt bubble. It seems to me that it may very well have also involved wages that were falling in inflation-adjusted terms for a significant number of wage-earners. I say this, because farmers were moving to the city in the early 1900s, as mechanization led to lower prices for food and less need for farmers. I haven’t seen figures on incomes of farmers, but I wouldn’t be surprised if they were dropping as well, especially for the many farmers who couldn’t afford mechanization. Wages for those who wanted to work as laborers on farms were likely also dropping, since they now needed to compete with mechanization.

In many ways, the situation that led up to the Great Depression appears to be not too different from our situation today. In the early 1900s, many farmers were being displaced by changes to agriculture. Now, wages for many are depressed, as workers in developed economies increasingly compete with workers in historically low-wage countries. Additional mechanization of manufacturing also plays a role in reducing job opportunities.

If my conjecture is right, the Great Depression may have been caused by problems similar to what we are seeing today–wages that were too low for a large segment of the economy, thus reducing economic growth, and a temporary debt bubble that tended to cover up the wage problem. Once the debt bubble collapsed, demand for commodities of all types collapsed, and prices collapsed. This problem was very difficult to fix.

When we add more debt to the economy, users of debt-financing find that more of their future income goes toward repaying that debt, cutting off the ability to buy other goods. For example, a young person with a large balance of student loans is unlikely to be able to afford buying a house as well.

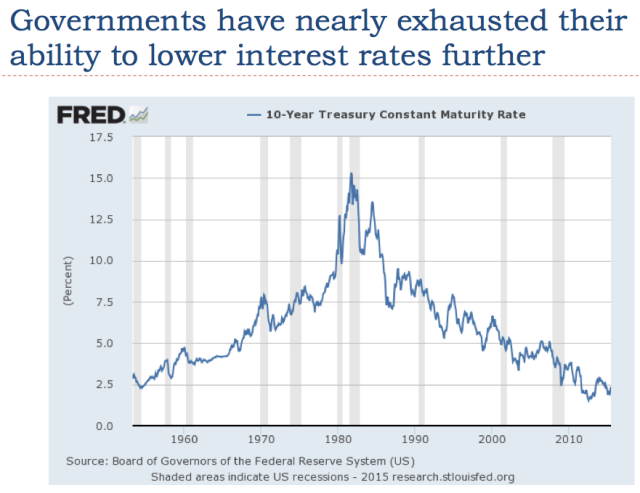

A way of somewhat mitigating the problem of too much income going toward debt repayment is lowering interest rates. In fact, in quite a few countries, the interest rates governments pay on debt are now negative.

If the cost of producing commodities continues to rise, but the price that consumers can afford to pay does not rise sufficiently, at some point there is a problem. Instead of continuing to rise, prices start to fall below their cost of production. This drop can be very sharp, as it was in 2008.

The falling price of commodities is the same situation we encountered in 2008 (Slide 27); it is the same situation we reached at the beginning of the Great Depression back in 1929. It seems to happen when wage growth is inadequate, and the debt level is not growing fast enough to hide the inadequate wage growth. This time around, we are also challenged by the cost of producing commodities rising, something that was not a problem at the time of the Great Depression.

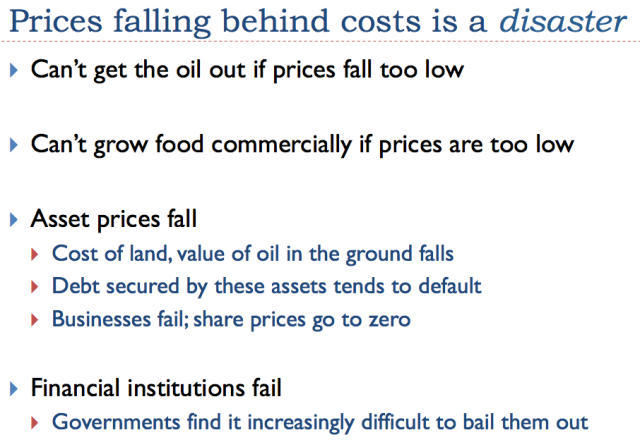

If we think about the situation, having prices fall behind the cost of production is a disaster. We can’t get oil out of the ground, if prices are too low. Farmers can’t afford to grow food commercially, if prices remain too low.

Prices of assets such as the value of farmland, the value of oil held by leases, and the value of metal ores in mines will fall. Assets such as these secure many loans. If an oil company has a loan secured by the value of oil held by lease, and this value falls permanently, there is a significant chance that the oil company will default on the loan.

The usual belief is, “The cure for low prices is low prices.” In other words, the situation will fix itself. What really happens, though, is that everyone is so afraid of a big crash that all parties make extreme efforts to avoid a crash. In fact, there is evidence today that banks are “looking the other way,” rather than taking steps to cut off lending to shale drillers, when current operations are clearly unprofitable.

By the time the crash does come around, it is likely to be a huge one, affecting many segments of the economy at once. Oil exporters and exporters of other commodities will be especially affected. Some of them, such as Venezuela, Yemen, and even Iraq may collapse. Financial institutions are likely to find themselves burdened with many “underwater loans.” The usual technique of lowering interest rates to try to aid the economy doesn’t look like it would work this time, because rates are already so low. Governments are not in sufficiently good financial condition to be able to bail out all of the banks and others needing assistance. In fact, governments may fail. The fall of the former Soviet Union occurred when oil prices were low.

Once there are major debt defaults, lenders will want to wait to see that prices will stay consistently high for a period (say, two or three years) before extending credit again. Thus, even if commodity prices should bounce back in 2017, it is doubtful that producers will be able to find financing at a reasonable interest rate until, say, 2020. By that time, depletion will have taken its toll. It will be impossible to make up for the many years of low investment at that time. Production is likely to continue falling, even if prices do rise.

The indirect impact of low oil and other commodity prices is likely to be a collapse in our current debt bubble. This collapsing bubble may lead to the failures of banks and even governments. It seems quite possible that these indirect impacts will affect us most, even more than the direct loss of commodities. These impacts could come quite quickly–in the next few months, in some cases.

Stocks, bonds, pension programs, insurance programs, bank accounts, and many other things of a financial nature seem to be very “solid” things–things that we can expect to be here and grow, for many years to come. Yet these things, directly and indirectly, depend on the ability of our system to produce goods and services. If something goes terribly wrong, we may find that financial assets have little more value than the pieces of paper that represent them.

I won’t try to explain Slide 36 further.

Slide 37 illustrates the principle of increased efficiency. If a smaller amount of resources and human labor can be used to create a larger amount of end product, this is growing efficiency. If more and more resources and labor are used to produce a smaller amount of end product, this is growing inefficiency.

The other part of the story is that simply automating processes is not enough. Instead, the economy must also produce a sufficiently large number of jobs, and these jobs must pay high enough wages that the workers can afford to buy the output of the economy. It is really the health of the whole interconnected system that is important.

Our low price problems are here now. That is why we need very cheap non-polluting energy products now, in large quantity, if there is any chance of fixing the system. These energy products must work in today’s devices, so we aren’t faced with the cost and delay involved with changing to new devices, such as cars and trucks that use a different fuel than petroleum.

Regarding Slides 39 and 40, we are sitting on the edge, waiting to see what will happen next.

The US economy temporarily seems to be in somewhat of a bubble, now that it does not have QE, while several other countries still do. This bubble is related to a “flight to quality,” and leads to a higher dollar, relative to other currencies. It also leads to high stock market valuations. As a result, the US economy seems to be doing better than much of the rest of the world.

Regardless of how well the US economy seems to be doing, the underlying problems of rising costs of producing commodities and prices that lag below the cost of production are still present, making the situation unstable. Wages continue to lag behind as well. We should not be too surprised if the economy starts taking major downward steps in the next few months.

Disclosure: None.

Comments

No Thumbs up yet!

No Thumbs up yet!