It’s A Conundrum Because It Wasn’t A Conundrum

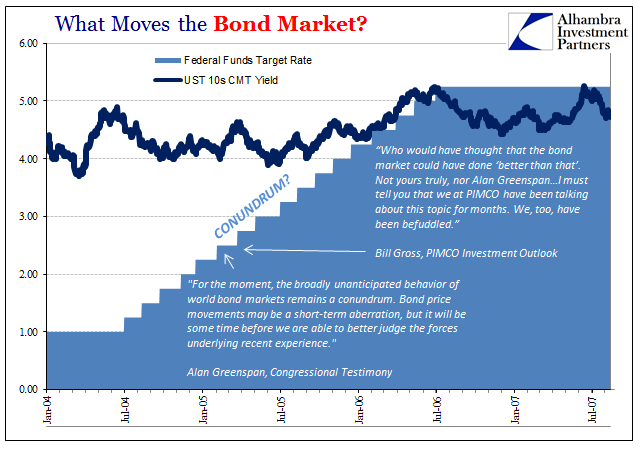

After the Fed “raised rates” a little over a week ago, the US treasury market responded with another collective shrug. Long-term rates fell rather than rose, having already responded that way to the prior two hikes. The word “conundrum” has sadly been revived.

It is unfortunate because treasury market behavior in the middle of the last decade was never a mystery. It only befuddled people like Alan Greenspan and Ben Bernanke who thought no disagreement was allowed. If the Fed was “tightening”, then according to the conundrum interpretation the economy could only be getting better. The central bank sets the direction and all markets must obey.

The issue was raised as early as March 2015 when similarly talk of “raising rates” elicited no agreement from the treasury market.

Even though Federal Reserve chair Janet Yellen strongly hinted last week that the Fed could boost interest rates in June, investors went out and bought even more bonds…

Current Fed chair Yellen hasn’t spoken about a bond conundrum just yet. But you have to wonder if she’s thinking about it.

For a prominent one like the UST market to elicits the tortured clutching of pearls. In 2005, though, bonds didn’t so much contradict the Fed and the mainstream narrative as express doubts about it. From the top-down perspective of policymakers, there might not have seemed much to worry about with the maestro still in command, especially with those hikes being his last official acts as Chairman. Outside of the economics bubble, it wasn’t any longer so simple.

The mid-2000’s were already showing the age of the Great “Moderation”, as well as exposing many of the contradictions that put the quotation marks around the word. Even faith in the Fed was strained by the dot-com bust that though did little to the downside seemed to have produced some negative effect on the upside. The last Fed “stimulus” rate cut was approved in June 2003, a year and a half after the dot-com recession officially ended.

If that wasn’t enough to give bond investors pause, there was the sudden and upfront matter of global money going haywire. Greenspan and Bernanke called it a global savings glut, but to most Americans it was a housing bubble no matter the cause. Periods of unbroken calm filled by enormous monetary anomalies don’t ever end well. The treasury market in the middle 2000’s was beginning to contemplate that ending.

Even then, however, it was not moved. The legend of the “maestro” as well as the assumed evidence of the Great “Moderation” to that point was given full weight and consideration. What resulted was paralysis; the battle over the Fed’s reputation versus growing signs that said reputation might not have been deserved.

The treasury market, represented by the benchmark 10-year yield, spent years trading in a suspiciously narrow range because there was no conviction one way or the other. For every additional rate hike conveying policy confidence, and there were seventeen altogether, there was the current account, the Bank of Japan’s comedy of errors, or the sudden proliferation of home flipper TV shows to counterbalance them. People had been conditioned toward believing with blind faith in orthodox economics, but for the first time in a generation there were clear signs why that might be a big mistake.

With a spectrum of possibilities so wide, it isn’t hard to understand why the bond market might just trade sideways no matter what. Until something conclusive turned up one way or the other to tip the scales, visibility, as they say, was extremely limited in this setting.

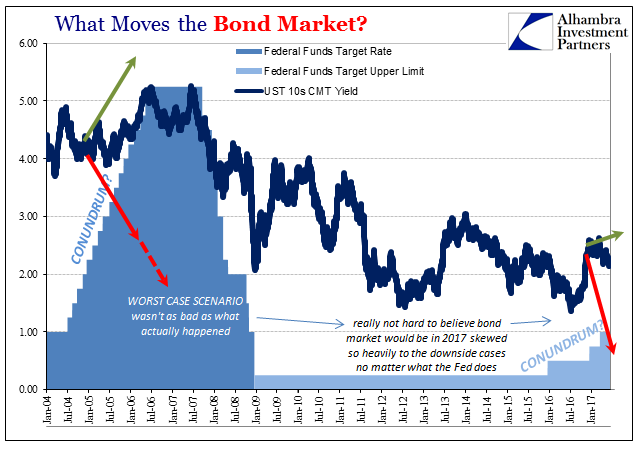

The issue would not be settled until July and August 2007. Those grave concerns proved to be, in the end, understated by more than a little. Greenspan wasn’t just wrong, but catastrophically so under his protégé Bernanke. The worst case contemplated in 2005 turned out to be far better than the global downside we find still in effect more than ten years later.

By inarguable history, the bond market, as eurodollar futures, has earned the benefit of the doubt that once belonged exclusively to the Federal Reserve and its central bank counterparts. Further, we have seen this process repeated in smaller doses and scales since. TIPS trading in 2013-14, for example, became similarly paralyzed (breakevens), caught between “reflation” and taper on the positive side and “dollars” plus recent history (meaning QE failures; if you have to repeat it, it doesn’t work) to the negative.

Unsurprisingly, the 2013-14 “reflation” though at times tantalizingly compelling failed in the same way. The Fed’s track record of being able to read the economy, not even craft and deliver effective policy, has been simply atrocious in the 21st century (it wasn’t all that good in the 20th, either). If the Fed “raises rates” in 2017 and the treasury market ignores it, there is a mountain of reasons why. There is no conundrum today, just as there wasn’t in 2005. What has changed is mere bond market doubts have become upfront disbelief.

The real mystery is why in the mainstream at least Janet Yellen as heir to what’s left of the legend is taken so seriously. The conundrum is a product of nothing more than instinctively taking economists at their word, even in action. The bond market stopped doing that fifteen years ago.

Disclosure: This material has been distributed fo or informational purposes only. It is the opinion of the author and should not be considered as investment advice or a recommendation of any ...

more