Incredibly Simple Economics

There are more than 300 Ph.D. Economists working on staff for the Federal Reserve. The central bank tells us that they “represent an exceptionally diverse range of interests and specific areas of expertise”. Perhaps, but they are all Ph.D. Economists, aren’t they? These highly educated people cover a broad range of topics, for sure, and all from the same starting point and perspective.

Believe it or not, the Fed has an entire research section devoted to Prices and Wages. It’s difficult to process given for four years we’ve heard from FOMC officials about the link between prices and wages starting from the unemployment rate. And we are still waiting for that forecast link to show itself.

That’s the problem when Ph.D.’s are advising Ph.D.’s about conclusions they’ve already drawn ahead of time. Economists may be diverse in their interests but their ideology prevents any sort of honest inquiry of discovery. Echo chamber.

The Section’s Chief is Dr. Kristin Hubrich, with Matteo Luciani her Chief Economist. Dr. Luciani’s current research topic, according to the Federal Reserve, isn’t the relationship between business profitability and wage growth, thus inflation in or out of a Phillips Curve setting, rather it is Non-Stationary Dynamic Factor Models. But of course, it is.

They feel the need to build better models because some of those we have now aren’t sufficient. I don’t mean the Fed’s models which have missed every big economic swing since they were first introduced, rather Dr. Luciani takes issue with other statistical constructions like GDP and GDI.

According to a paper he co-authored with Matteo Barigozzi of the London School of Economics for the Federal Reserve Board earlier this year, over the past few years GDP and GDI together may have been understating growth. If the two Matteo’s are right, there was little or no downturn in 2015-16, no labor market slowdown thereafter, and the unemployment rate isn’t just a fanciful picture of an incomplete denominator.

Yellen was right all along – if you just change the numbers.

In this note, we introduce a new estimate of GDO [Gross Domestic Output] obtained from a Non-Stationary Dynamic Factor model estimated on a large dataset of US macroeconomic indicators. Compared to the approaches of the BEA and the Philadelphia Fed, our estimate of GDO incorporates information coming from a wider spectrum of the economy, and this additional information empirically proves to be non-trivial. Indeed, our estimate of GDO offers a different picture of economic activity: according to our estimate, since 2010 quarterly annualized GDO growth was on average 1/2 of a percentage point higher than estimated by the BEA or the Philadelphia Fed, thus showing a more rapid pace of improvement than measured by national account statistics.

This kind of investigation isn’t unique at the Fed nor any other research division from another central bank. This is what they do. Maybe they have so much time to dream about saving Economics because our actual economic predicament is really straightforward and easy to demonstrate.

Despite this economic boom, workers and therefore consumers don’t appear to be benefiting much from it. If they aren’t, it really can’t be much of a boom.

This isn’t a new development, but the situation has worsened since that last downturn more than two years ago. Incomes have tracked the participation problem closely, but that doesn’t explain 2016 and onward when the unemployment rate dived lower than any models anticipated. Aggregate labor income continues to be stagnant even with that rate around and below 4%.

The Personal Income and Spending update for August 2018, released by the BEA today, shows for still another month nothing has changed. Income growth is tepid and is, in fact, less than spending, meaning that even factoring the revisions to Proprietors’ Income at the last benchmark incomes don’t come anywhere close to matching the unemployment rate.

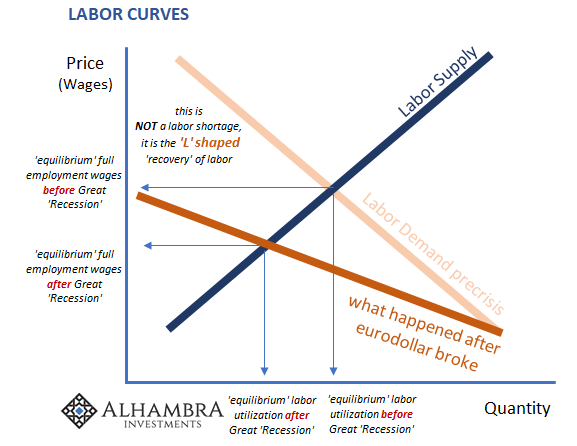

This is where the constant supply of mainstream anecdotes about a LABOR SHORTAGE!!! backfires. Each one only proves that companies are doing everything they can, except to pay more for workers. It’s almost as if they can’t pay for them – which is exactly what’s going on here.

Again, this is pretty simple economics (small “e”), requiring no doctorate or formal economic training to appreciate.

At times when companies don’t make money, profit growth slows or reverses, they pay very close attention to their costs. This is about as uncontroversial as it gets. They may even be forced into extreme adjustments like layoffs if their bottom lines are really threatened.

Businesses may also simply refuse to hire many more workers or pay a lot for them as well as their existing labor force. If profitability is in doubt, the last thing any company will do is be aggressive on costs. Labor is almost always the biggest cost.

While the 2015-16 downturn was a manufacturing recession, it was also a profit recession, too. In other words, while not all businesses were tied to the fortunes of crashing commodity prices they were impacted nonetheless. They tightened up their cost practices and aggregate income growth even contracted ever so slightly for eight months (after October 2015), an even bigger contraction in non-linear terms. That was the full reach of the downswing.

Profits have never really come back, though. As noted yesterday, profits aren’t any higher in the latest data for Q2 2018 than they were in 2014 or are they really that much more than 2012. The “rising dollar” downturn may not have visited a profit recession on everyone, but it does seem to have been a wakeup call that economic recovery wasn’t going to show up even after QE3 and QE4.

Indeed, the sluggish profit recovery in the rest of 2016 and 2017 merely confirmed the lack of acceleration and therefore explains the persistent reluctance of businesses, in the aggregate, to pay an accelerating wage for marginal labor. There is practically no demand for marginal labor regardless of the wage.

If you struggle to make money, you don’t hire more workers nor enthusiastically bid up the price for them. It is just that simple: economics, not Economics. Not only is it simple, that’s what all the data shows.

Rather than appreciate this honest, consistent, and corroborated verdict, 300 Ph.D.’s are doing what? They sure aren’t investigating why QE failed 4 times (just here in the US) to change the economic and therefore profit picture for businesses. They don’t seem all that interested in this as a possibility, even in the Prices and Wages Section.

Say what you want about Milton Friedman on the topic of inflation and monetary policies, but he got this part right:

The difficulty of having people understand monetary theory is very simple—the central banks are good at press relations. The central banks hire people and the central banks employ a large fraction of all economists so there is a bias to tell the case—the story—in a way that is favorable to the central banks.

No kidding.

Disclaimer: All data and information provided on this site is strictly the author’s opinion and does not constitute any financial, legal or other type of advice. GradMoney, nor Jennifer N. ...

more

A very good and straightforward article and synopsis. I suggest that people read it. A main issue is as efficiency, automation, and logistics increasingly improve, how do we increase salaries and income for a majority of people so that consumption can increase. Lower interest on credit only goes so far. Inevitably wages and income must improve to sustain strong economic growth.