Buybacks Get All The Macro Hate, But What About Dividends?

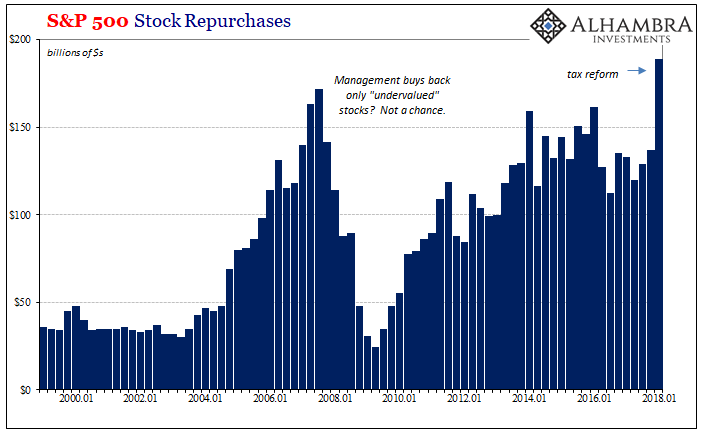

When it comes to the stock market and the corporate cash flow condition, our attention is usually drawn to stock repurchases. With good reason. These controversial uses of scarce internal funds are traditionally argued along the lines of management teams identifying and correcting undervalued shares. History shows, conclusively, that hasn’t really been true.

Last year’s tax reform law was meant ideally to spur corporate repatriation of cash. All indications so far in 2018 show that has happened to some debatable degree. Cash has come home, though it’s not yet clear how much or how much will keep coming.

Nor is it clear why it has come home. The law’s intent was to create a channel whereby “stranded” overseas cash could be deployed domestically without corporations suffering the penalties imposed by America’s insanely outdated tax code. Corporate spending is up in Q1, as reported by Standard & Poor’s. Unfortunately, as was predictable, a significant proportion was used for realized stock buybacks.

According to S&P, for the 500 companies in the main stock market index share repurchases hit a record $189.05 billion in Q1, finally surpassing the peak in 2007. What stands out in my mind, however, is not really what happened in Q1 2018 so much as why it might have taken so long for it to have happened.

There is a clear rhythm to aggregate buybacks just as it there is for the related issue of dividends. In the end, it might be this other shareholder cash constraint that is of more useful interest along macroeconomic lines.

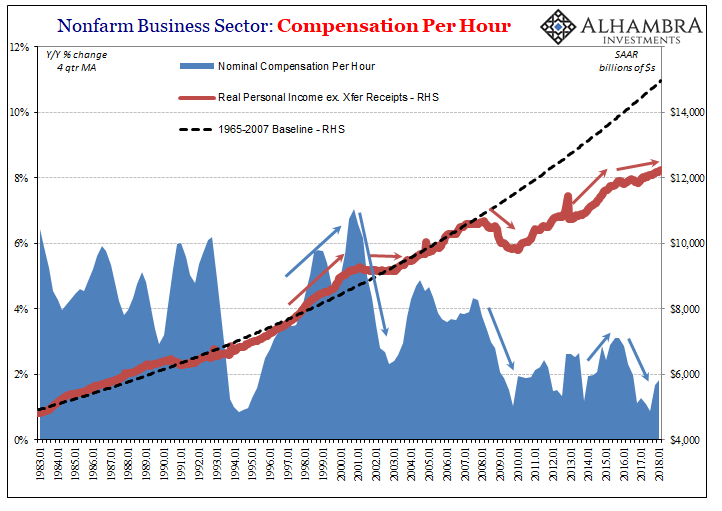

In terms of these payments also reported by S&P, corporations have been remitting a lot more out of their earnings (“as reported” EPS) going back to the end of 2014. That makes sense given how the “rising dollar” downturn first took an enormous bite out of corporate profits in the energy sector and then increasingly everywhere else (to a lesser degree than in energy). To maintain dividend streams in the absence of profit growth necessarily meant paying more of reduced profits to keep them flowing to shareholders.

That’s not the full extent of it, either.

Because bottom lines were being smashed by the 2015-16 downturn, companies couldn’t keep expanding dividend payments as they had been doing up to that time. Dividend growth decelerated, too, leaving companies to ponder the prospects of paying more of their corporate earnings even in slower growing dividend payments.

With the stock market’s rise in many respects having been predicated on steady dividend growth against the background of ZIRP, the danger at least to generic corporate management was pretty clear.

What to do about this cash flow constraint such that it doesn’t threaten share prices any further? How about a hiring/wage freeze?

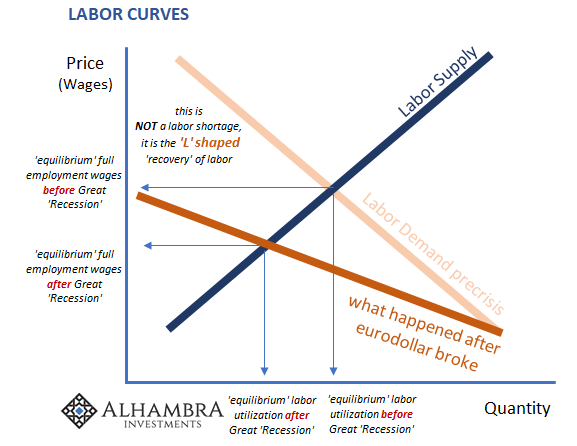

We have to consider that dividend commitments, current and future, might have played a significant role in truly undermining the unemployment rate view of the labor market and therefore economy. (NOTE: the big jump in personal income at the end of 2012 was due to personal income tax changes rather than any labor market factor, but the higher dividend payouts in 2012 as profits suffered during that particular downturn are likely to have affected income growth, the “L”, following that near recession, too.)

This would help explain why lack of profit growth may have kept companies from paying the market clearing wage so as to alleviate whatever parts of the LABOR SHORTAGE!!!! is being reported on as a systemic factor it clearly isn’t. Corporations may be becoming more creative about finding workers so as to fill all these news stories about that creativity, but they remain conspicuously unwilling to take the utterly simple economic solution and just pay what is demanded.

This is the vast difference between data and anecdotes.

If it appears as if they won’t pay it is in all likelihood because they can’t pay. Thus, there is no labor shortage, merely an economic problem misunderstood and often purposefully mischaracterized. Companies require actual rather than imaginary profit growth so as to be able to pay out existing dividend (and stock repurchase) commitments first and then have enough left over to raise worker pay and aggressively add to staff at those higher rates.

This is in some ways indicated by current estimates for 2018, but before getting too excited we have to note several hurdles in the way of any such labor market resolution. The first is the profit estimates themselves. They are almost certainly too high, as per usual. As those estimates come down so will the dividend ratio rise back closer to levels unfortunately consistent with the past few years.

Second, we have to suspect that corporate managements are itching to raise dividends at a faster pace than they have been forced to since early 2015. That would mean whatever profit growth might be realized in the coming quarters could first be deployed by accelerating dividends before accelerating worker pay.

Lastly, there is the increasingly uncomfortable prospect of renewed downturn before any of those positive elements really get going. Another bout of “dollar” deflation would, as in early 2015, degrade all factors simultaneously all over again.

Not only does this all help explain the now several years of “missing” wage acceleration, it also answers the ridiculously low unemployment rate itself. Companies really aren’t hiring new workers all that quickly for the same reasons they are so reluctant to pay more for keeping those they have, and luring replacements for those that naturally depart. Everything indicates how the labor force is stagnant.

Once more, it’s not a labor shortage but a cash flow shortage generated by a macro shortage. It makes one wonder what another “L” in the series might really look like. Not 3.8% or 4.0% true unemployment, that’s for sure.

Disclosure: None.