Why We Don’t Own Bank Of America

Bank of America (BAC) is a fine company that is committed to making financial lives better. Most of its financial crisis problems are now behind it, and it may continue to increase its dividend going forward. And thanks to new regulations, it’s now safer and less volatile than it was before the financial crisis. However, we still don’t own shares of Bank of America for a variety of reasons including its limited long-term growth opportunities, its high cost of capital versus its low return on capital, low interest rates, its already fair valuation, and its unimpressive dividend, to name a few.

Overview:

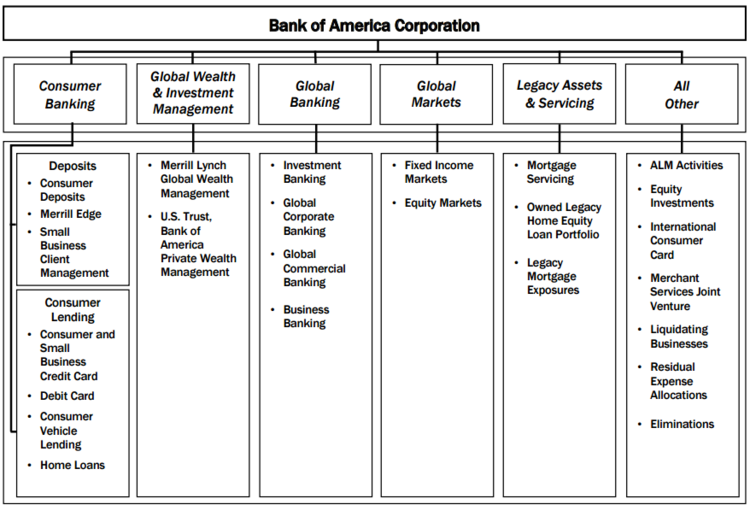

Bank of America’s mission is “to make financial lives better by connecting those we serve to the resources and expertise they need to achieve their goals.” (Annual Shareholders Letter, p.1) They execute on their mission through five main operating segments as shown in the following chart:

(annual report, p.30)

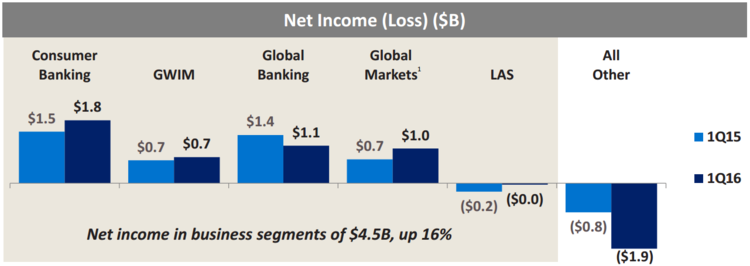

And for reference, the recent net income for each segment is described below:

(investor presentation, p.24)

Worth noting, the net loss of Legacy Assets & Servicing (LAS) segment has declined dramatically versus earlier time periods because the financial crisis is now further in the rear view mirror (for reference, LAS is the segment that deals with loans originated prior to January 1, 2011 that would not have been originated under more current underwriting standards). So far this year the net loss for LAS has been only $0.2 billion whereas it was $13.1 billion for the full year 2014 (annual report, p.40). According to CEO Brian Moynihan, the company is “no longer clouded over by heavy mortgage and crisis-related litigation and operating costs.” (annual report, p.1).

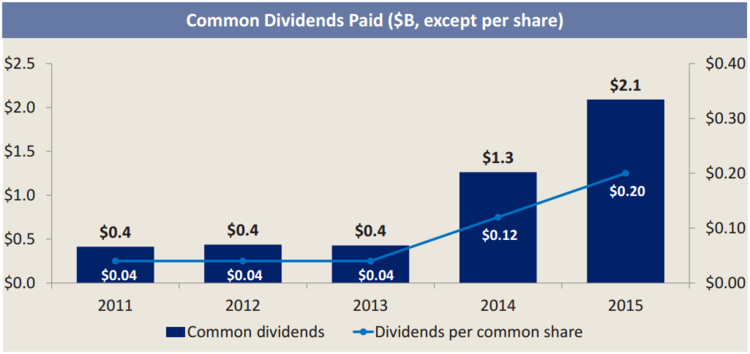

Additionally, as the impacts of the financial crisis recede, BAC has been allowed by regulators to increase their dividend payment as shown in the following chart.

(investor presentation, p.14)

BAC’s dividend yield currently sits at around 1.3% (GoogleFinance), which is better than it was before, but still not particularly impressive when compared to some of its peers (for example Well Fargo’s is around 2.9%). Additionally, BAC’s dividend has the potential to keep growing.

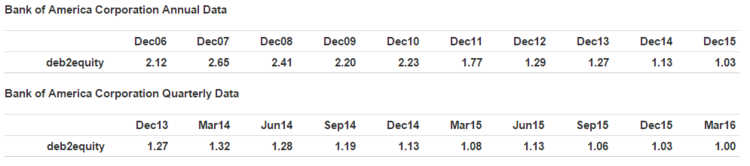

Also important, we believe BAC is much safer now than it was before the financial crisis because of all of the new rules and regulations. According to Brian Moynihan “we are doing all we can [in] optimizing our balance sheet to perform efficiently with the post-crisis regulations we must follow.” (annual report, p.6). For example, BAC is now taking on much less risky leverage than before the financial crisis as shown in the following debt to equity (leverage ratio) table.

However, despite BAC’s safer business and increased dividend, we are still not a buyer. Here’s why...

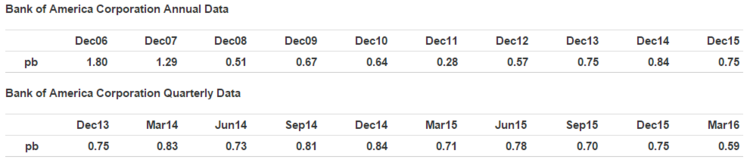

Limited Long-Term Growth Opportunities: For starters, we believe the same lower leverage that makes BAC safer, also limits its return opportunities. The higher risk of higher leverage also brought higher returns, but now as leverage has come down (as shown previously) so too have return expectations. To further quantify this, BAC (and banks in general) used to trade at higher price-to-book values because they could leverage up their book to earn higher returns (albeit with higher risk). As shown in the following table, BAC’s price-to-book was 1.8x in December of 2006 before the onset of the financial crisis. However, now it sits at only 0.75x (less than half) because it’s taking on much less risk (more on valuation later).

Reduced leverage is not the only way regulators have reduced risk/return opportunities for big banks. The types of risks banks are allowed to take have also been reduced. For example, banks have been required to shed much of the riskier distressed assets from their balance sheets post-financial crisis. And while this was a boon for hedge funds and loan servicers that specialized in higher risk assets, it hurt the returns of the banking industry and it will likely continue to do so going forward because it limits their return opportunities.

Another reason why BAC has lower long-term return opportunity is because competition is intense in the industry. Bank of America is already enormous, the market is very saturated with other banks, and it may be realistic to assume BACs opportunities may only grow at roughly the same rate as GDP (i.e. 1-3% per year if we’re lucky). Further, Bank of America has embarked on a wide-scale cost cutting campaign (which has been successful so far), but cost-cutting can only go so far in improving profitability before the business begins to suffer.

Cost of Capital Exceeds Return on Capital: Another reason why we don’t like Bank of America is because the company’s cost of capital exceeds its return on capital. This means that Bank of America destroys value with every new dollar it invests. Specifically, BAC’s weighted average cost of capital is around 5.9%, and its return on invested capital (using TTM of income statement data) is only 4.4%. This value destroying relationship is true of some other big banks (e.g. Citigroup), but not true of all of them (e.g. Wells Fargo). A similar value destroying relationship is true of BAC’s cost of equity (~11.3%) and its return on equity (3.4%).

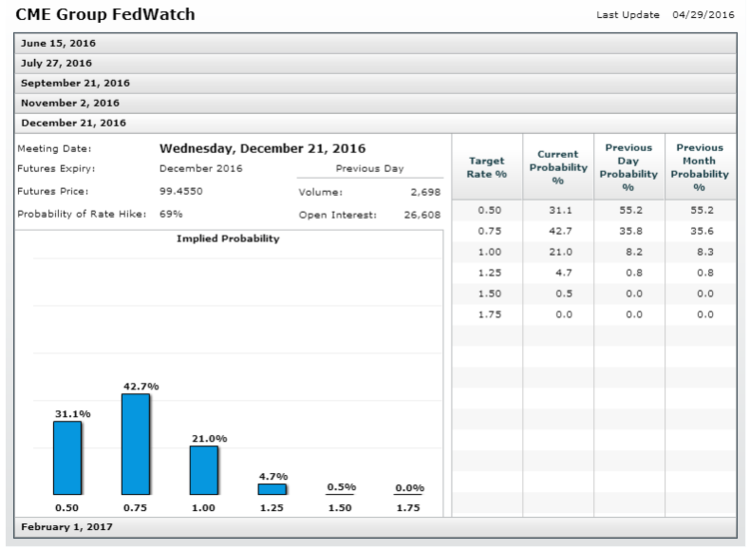

Low for Longer Interest Rates: Low interest rates are another factor working against Bank of America and banks in general. Traditionally, banks make money on their net interest margin (i.e. the rate they receive on their investments minus the rate they pay to depositors). And banks need interest rates to go up to improve their margins and profits. Unfortunately, the Fed’s artificially low interest rates are not helping net interest margins. However, some banks (for example, Wells Fargo) are able to optimize other sources of revenue (i.e. fee revenues) in a way that allows them to have a return on capital that exceeds their cost of capital despite the low interest rate environment. On the other hand, this is not the case for BAC. And even though the Fed is expected to slowly increase rates, they’ll still likely be low for many years to come. For example, the CME’s FedWatch predicts rates will remain very low through at least the end of this year.

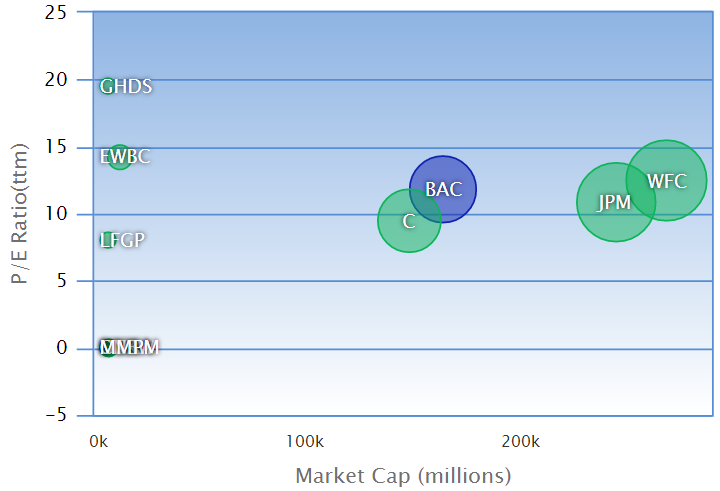

BAC is already fairly valued: In our view, Bank of America is already priced fairly. For example, as the following chart shows, it trades at an earnings multiple similar to its peers.

(Source: GuruFocus)

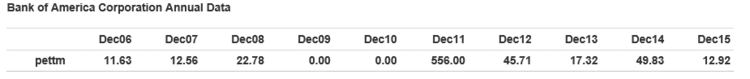

Additionally, the following table shows BAC’s earnings multiple isn’t sharply different than at other “normal” times. For example, in 2006-2007 (before the onset of the financial crisis) BAC’s price-to-earnings ratio was similar to what it is right now.

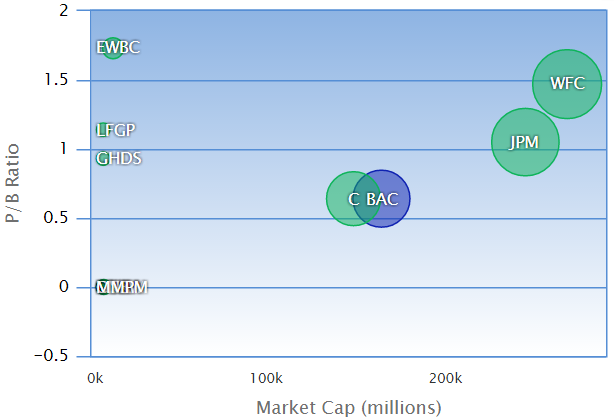

Price-to-book is another important valuation metric for banks. We already discussed how BAC’s price-to-book ratio has come down since it now takes on less leverage following the financial crisis. However, it’s also worth noting that BAC’s price-to-book is not an outlier versus peers as the following chart shows:

It’s worth noting that BAC’s price-to-book is more similar to Citigroup (C) largely because these company’s assets are considered riskier and because their cost of capital is higher than their return on capital. Wells Fargo (WFC) and JPM are assigned higher price-to-book ratios by the market because they tend to offer a better return on capital.

The dividend is not impressive: Another reason we don’t own Bank of America is because its 1.3% dividend yield is relatively unimpressive. Given the regulation-induced lower volatility and lower expected returns, we’d expect a higher dividend yield to make this stock compelling. However that’s not the case, and we don’t expect BAC to raise its dividend dramatically anytime soon. On the other hand, BAC’s peer, Wells Fargo, is already paying a dividend yield of nearly 3.0% which is well above the S&P 500 average.

Conclusion:

There may come a day when bank stocks trade like utilities insofar as they’d pay high dividends and exhibit lower volatility. But we’re not there yet. And if you are going to diversify your portfolio into bank stocks (diversification is a good thing) then we much prefer banks that pay decent dividends and earn returns that exceed their cost of capital. For example, our recent article titled: Wells Fargo: Big Dividend, Attractive Valuation. We have nothing against Bank of America (it’s a fine company that helps people improve their financial lives), it’s just not a stock we care to own.

Disclosure: None.

Another reason why we don’t like Bank of America is because the company’s cost of capital exceeds its return on capital. This means that Bank of America destroys value with every new dollar it invests. Specifically, BAC’s weighted average cost of capital is around 5.9%, and its return on invested capital (using TTM of income statement data) is only 4.4%. This value destroying relationship is true of some other big banks (e.g. Citigroup), but not true of all of them (e.g. Wells Fargo). A similar value destroying relationship is true of BAC’s cost of equity (~11.3%) and its return on equity (3.4%).

This is a good enough reason in itself. The sad fact is many TBTF banks forgot how to do banking and would die if they couldn't get zirp or near zirp borrowings and loan out to the public at absurd rate differentials. They need to be dismantled or die like the dinosaurs.