Canada’s Failing Energy Strategy

On July 6, 2013, 47 residents of Lac-Megantic, Quebec died horribly when a 74-car freight train carrying crude oil exploded in a fireball. It was the deadliest freight-train accident in Canadian history. Five bodies were never recovered and were assumed to have simply vaporized. DNA samples were required to identify others. Heat from the inferno was felt over a mile away.

In spite of this tragedy, moving crude by rail (CBR) is comparatively safe. Since 2013, safety standards have been tightened throughout North America. The International Association for Energy Economics (IAEE) found the incidence of spills with CBR to be less than for pipelines. However, this is a deceptive statistic. Once you adjust for the greater volumes of crude moved by pipeline versus CBR, as well as the greater distances covered, pipelines remain substantially safer. The report concludes that, “the risk associated with shipping crude oil is noticeably larger for rail deliveries than for pipeline deliveries.”

2,500 miles west, off the coast of Vancouver, live around 75 endangered killer whales. Their connection with Lac-Megantic is not obvious. Fortunately for the Orcas, vocal advocates have successfully made their continued survival more important than avoiding another freight train tragedy. By blocking the Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion, they have ensured that more Albertan crude oil will reach its buyers by rail, given continued inadequate pipeline capacity.

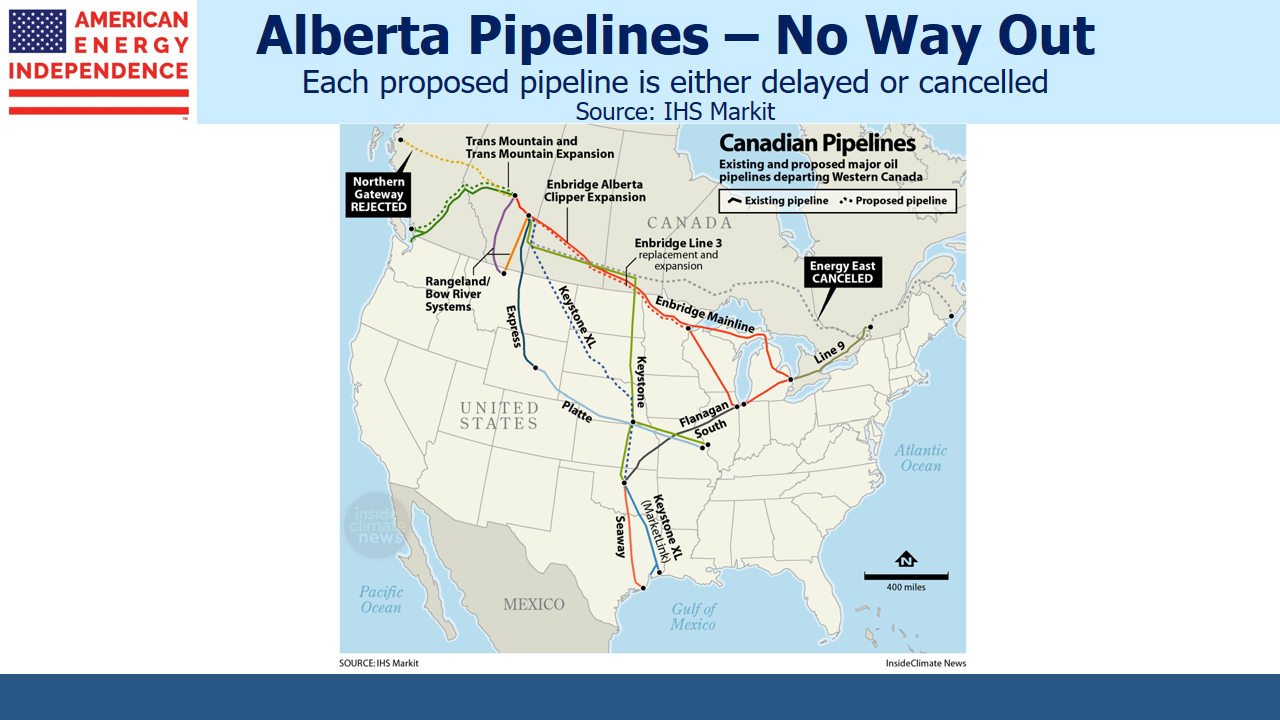

The Trans Mountain Pipeline (TMX) was put into service in 1953, and has been in continuous operation ever since. It’s another example of the long life of installed energy infrastructure, which generally appreciates in value when properly maintained even while accounting rules allow for its depreciation. Kinder Morgan (KMI), which acquired the pipeline in 2005, had been frustrated in its efforts to more than double the capacity of TMX by adding a second pipeline alongside the first. The TMX Expansion’s approval became a provincial political football. Land-locked Alberta has few choices in exporting its crude oil.

British Columbia sought to prevent a new pipeline from Alberta reaching the Port of Vancouver. Oil that passes through on its way to export markets has little value to local residents, since British Columbia doesn’t need any more oil. Environmentalists worried about a spill, and regard Albertan oil-sands crude as exceptionally hostile to the environment (it’s true that an oil sands facility is not pretty). First Nations tribes claimed their water supplies were threatened, although of 133 indigenous groups consulted, 43 were in support. And the anticipated increase in tanker traffic at the port of Vancouver, from two to ten per week, risked displacing the dwindling community of killer whales.

It was this last point that prompted the Federal Court of Appeal to overturn the government’s approval of the expansion in late August. Although the absence of a meaningful dialogue with First Nations representatives was cited, failure to consider the increased tanker traffic, “was so critical that the Governor in Council could not functionally make the kind of assessment of the project’s environmental effects and the public interest that the (environmental assessment) legislation requires,” said the ruling, written by Justice Eleanor Dawson. Canadian law provides wildlife with considerable protections.

In a deft move, KMI had by now extricated themselves from the vagaries of Canadian energy policy. For months, they had complained about the impossibility of building a pipeline linking two provinces holding opposite views on its completion. Finally, in May they unburdened themselves of the whole sorry mess and sold TMX to the Canadian Federal government for C$4.5BN, viewed by many as a pretty full price. KMI shareholders dodged a bullet.

A few weeks after agreeing the sale of TMX, KMI estimated in a filing that completion of the expansion would cost C$1-1.9 Billion more than originally expected and take a year longer. On August 30, KMI shareholders formally approved the sale, hours after the Court of Appeal ruling. TMX was by now worth considerably less than the C$4.5 Billion paid — the bailout by Canadian taxpayers was complete.

Prospects for the TMX Expansion are uncertain, with a delay of two years or more seemingly inevitable. The Canadian government is considering an appeal, redoing its environmental review, and crafting legislation to force it through. Canada wants to complete the pipeline. Meanwhile, Alberta grumbles about contemplating separatism, and has in the past suggested that it might halt crude oil shipments to British Columbia altogether.

Canadian crude oil will continue to reach its buyers, although more of it will move by rail. The International Energy Agency expects CBR shipments to double over the next two years due to lack of pipeline capacity. Suncor, Canada’s largest oil and gas producer, won’t expand crude oil production until it sees progress on pipeline approvals. The persistent $25-35 per barrel discount of Western Canadian Sedimentary crude to the WTI benchmark is directly linked to limited transportation choices, and must be regarded as a huge success by Alberta’s neighbors in British Columbia. Since the U.S. is both its biggest energy customer and nowadays its biggest competitor, Canada’s position is unenviable.

American readers will be relieved that such extreme dysfunction doesn’t exist in the U.S. Recall though, Boston’s annual winter imports of liquefied natural gas from Trinidad and Tobago to keep the lights on. Pipeline opposition isn’t limited to our northern neighbor (see An Expensive, Greenish Strategy).

The investment takeaway is that opposition to new pipelines increases the value of those already installed. When shippers resort to rail to move crude oil, their bargaining position on pipeline tariffs is weak. Oil and gas companies suffer lower revenues, consumers higher prices, and railway lines benefit if demand is sustained long enough to justify their capex. But for pipeline companies, installed pipelines with decades of useful life can represent a scarce resource. If the possibility of excess pipeline capacity concerned markets during the 2014-16 energy sector collapse, we are now headed solidly in the other direction.

Disclosure: We are long KMI.

Protecting whales is not dysfunctional. Protecting Monterey Bay in California is not dysfunctional either.