New York Times Forecasts The 2014-16 Energy Sector Collapse

One official says the shale industry may be “set up for failure.” “It is quite likely that many of these companies will go bankrupt,” a senior adviser to the Energy Information Administration administrator predicts.

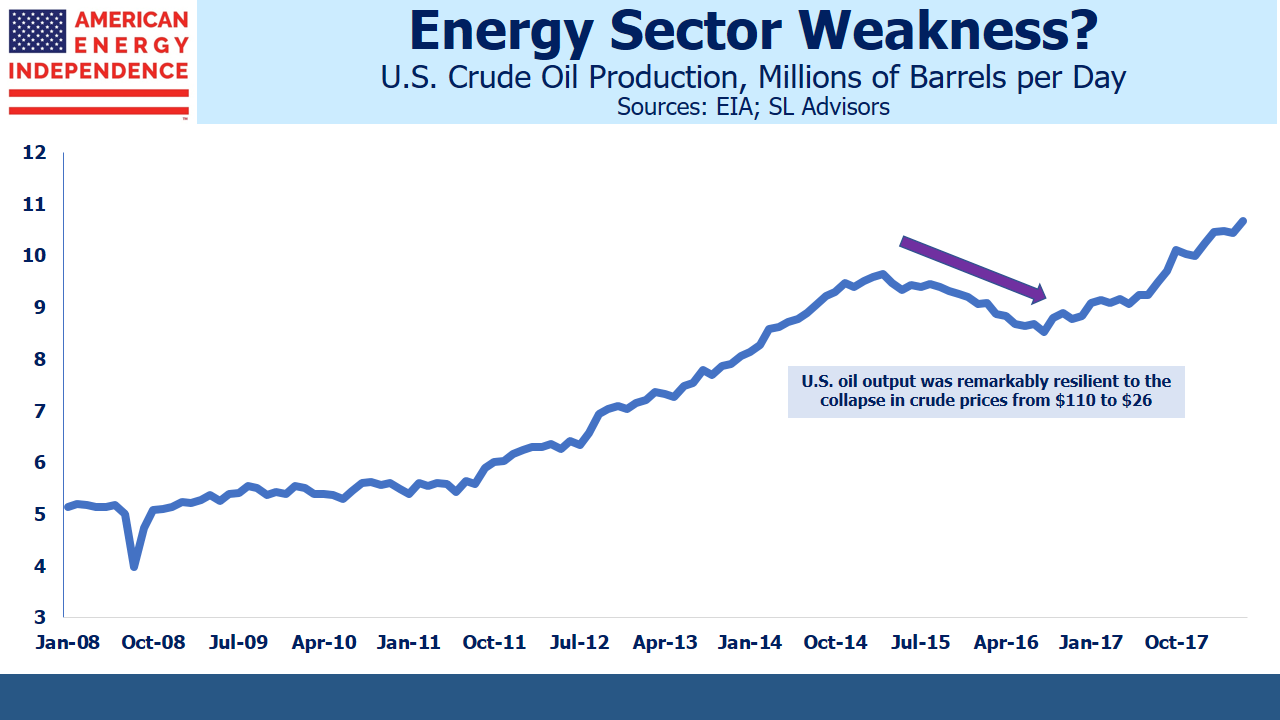

This is from the New York Times. However, it wasn’t part of The Next Financial Crisis Lurks Underground, Bethany McLean’s recent article promoting her upcoming book. In 2011, the NY Times ran a series of articles by Ian Urbina that was critical of many aspects of the Shale Revolution, including the shaky finances underlying its companies. In the ensuing seven years, U.S. crude oil production has doubled and we’ve moved from planning imports of Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) to exporting it. Behind the Veneer, Doubt on Future of Natural Gas, Urbina’s June 2011 article predicting failure, was spectacularly wrong.

Hydraulic fracturing (‘fracking”) is how shale extraction of oil and gas has revolutionized America’s energy security. It has its opponents, whose worries include water contamination and earthquakes. We are environmentalists too – it is everyone’s environment. We like the reduced CO2 emissions made possible by natural gas substituting for coal-burning power plants (see Guess Who’s Most Effective at Combating Global Warming). Robust regulation is in everyone’s interests, so that the Shale Revolution’s benefits can continue to outweigh its costs. The NY Times has a long history of criticizing fracking.

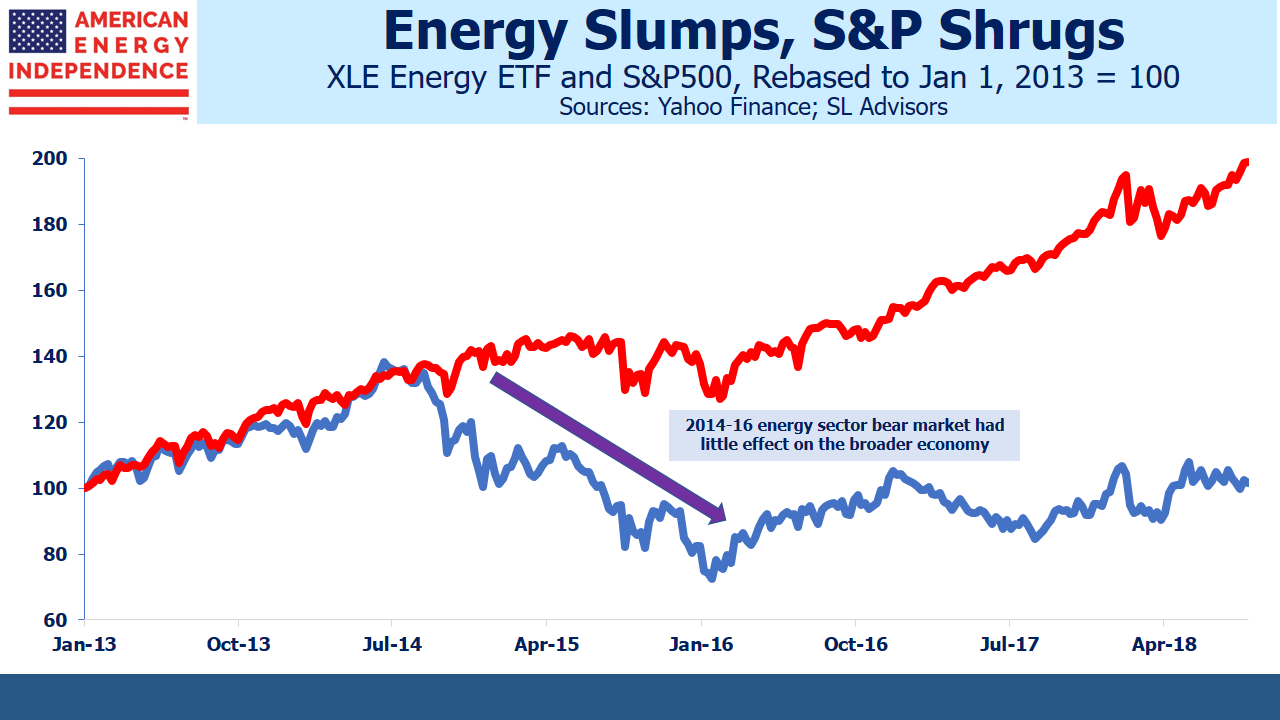

Ms. McLean’s essay was appropriately in the Op-Ed section, which acknowledges that it’s not intended as a news article. Her previous book, The Smartest Guys in the Room, recounted the collapse of Enron and was published six years after Skilling and Co’s demise. Similarly, Ms. McLean is forecasting a crisis in the energy sector after it’s already occurred. From June 2014 to January 2016, the Energy SPDR ETF (XLE) dropped 44%. An over-leveraged industry was hit by falling crude oil, which plummeted from $110 per barrel to $26. Investors complained that cash was being excessively reinvested in new wells, leaving too little available to be returned to investors via dividends or share buybacks.

Moreover, the energy sector endured its collapse pretty much alone. The rest of the U.S. economy shrugged. There was no recession, and the broader stock market averages meandered mostly sideways. During this period, Alerian’s MLP Index fell by 58.2%, more than during the 2008 financial crisis. It’s hard to imagine a more adverse scenario for America’s energy sector, and it suffered in isolation with no collateral damage. Bethany McLean may have missed all this; she might just as well breathlessly announce that the Philadelphia Eagles are about to win their first Super Bowl (note to non-U.S. readers – the Eagles did this in February).

Since then, leverage has been falling, profitability rising and investors have been receiving more cash (see U.S. Oil Producers Continue To Chart Path to Long-Term Growth). Ms. McLean pays this little heed. She notes that, “By mid-2016 American oil production had declined by nearly a million barrels a day” although this relatively modest drop testifies to the resilience of the business, not its frailty. To assert that, “…the Federal Reserve is responsible for the fracking boom…” because of low interest rates sounds as if the Fed’s bond buying program included the debt issued by energy companies. Fed policies have increased risk appetites for equity of all kinds, increasing the competition for capital from non-energy sectors.

The energy sector is slowly recovering from its 2016 low, and the first question of potential investors is about a repeat of $26 oil. Free cash flow yields on the American Energy Independence Index are 9.5%, almost twice the S&P500 (see Reliable Yields Are the Best). This doesn’t look like a bubble.

The fast decline rate of shale wells that Ms. McLean criticizes are in fact a substantial risk mitigant. It’s how shale drillers earn back their invested capital more quickly, and is why the world’s biggest oil companies are substantially investing in North America (see The Short Cycle Advantage of Shale).

Because The Next Financial Crisis wasn’t published in 2015, it’s of little actionable use. However, the upcoming book from which it’s drawn (Saudi America; The Truth About Fracking and How It’s Changing the World) may well be interesting. It’ll probably be more useful as history than as a forecast.