Elliott R. Morss, Ph.D. ©All Rights Reserved

Introduction

In earlier writings, I have pointed to the primary shortcoming of democracy as a form of government. Special interest groups get what they want via lobbying and campaign contributions while the general question of what is good for the country is put on the back burner. An excellent example of this is what Eisenhower warned about – the military-industrial complex. The complex is not happy unless the US is at war. And for the last 60 years, it has gotten what it wants: since Vietnam, the US has almost always been at war, wars of questionable merit. The military-industrial complex has been helped along by an electorate that is stunningly uninformed on global matters.

Recently, a new book questions this focus on special interest groups as being at the root of the problem. In “Inside Job: How Government Insiders Subvert the Public Interest”, published by Cambridge University Press and available online through Internet outlets like Amazon and Barnes & Noble, Dr. Mark Zupan focuses on government officials who find ways to enrich themselves while subverting the “national interest.” Zupan has been the 14th president of Alfred University, located in upstate New York, since July 2016. He holds a B.A. and Ph.D. in economics from Harvard and MIT, respectively. He has previously served on the faculties at USC’s Marshall School of Business, the University of Arizona’s Eller College of Management, Dartmouth’s Tuck School of Business, and the University of Rochester’s Simon Business School. He was Associate Dean of MBA programs at Marshall and a two-term business school dean at both Eller and Simon.

I quote from Zupan:

National decline is typically blamed on special interests from the demand side of politics corrupting a country’s institutions. The usual demand-side suspects include crony capitalists, consumer activists, economic elites, and labor unions. Less attention is given to government insiders on the supply side of politics – rulers, elected officials, bureaucrats, and public employees. In autocracies and democracies, government insiders have the motive, means, and opportunity to co-opt political power for their benefit and at the expense of the national well-being.

So who is to blame: the special groups outside of government or the government officials who subvert the national interest? Of course, it is not really an either-or question. The complicity of both groups is needed. But one can question the relative importance of each player. To look more closely at this, Dr. Zupan has agreed to be part of a Q & A session with me.

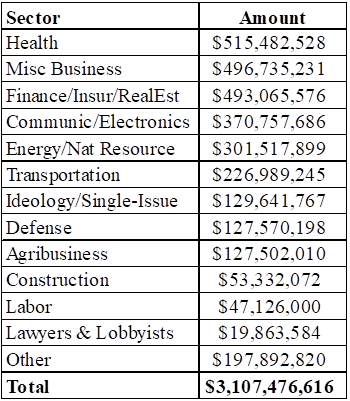

Elliott: Generalizations are problematic. So let’s start with the US. I would argue that in the US, most politicians do not view getting elected as a way “to line their wallets.” They go to Washington hoping to represent the people that elected them in a responsible manner. But as soon as they arrive in DC, they encounter lobbyists. They are “sitting ducks.” Table 1 provides lobbying expenditures by industry in 2016. There are 11,166 registered lobbyists working in DC.

Table 1. – Lobbying Expenditures by Industry, 2016

Source: Open Secrets

Mark: Demand-side interests definitely matter more in democracies than in autocracies. That said, we cannot ignore the role that supply-side interests play in democracies such as the United States. And it’s not just the pecuniary interests of individuals on the supply-side of politics in democracies that matter. We also have to take into account the role played by the non-pecuniary, ideological goals of individuals on the supply side of politics.

On the pecuniary side, there are well-known cases from both sides of the political aisle--individuals such as Gingrich, Hastert, LBJ, and the Clintons—who have done well financially due to their government ties. There are also studies by economists Alan Ziobriowski, James Boyd, Ping Cheng, and Brigitte Ziobrowski on the performance of financial portfolios of members of Congress prior to the passage, in 2012, of the Stop Trading in Congressional Knowledge (STOCK) Act. The average senator’s portfolio beat the market by more than 12 percentage points per year over a 15-year period prior to the STOCK Act while members of the House saw their portfolios appreciate by an average of 6 percentage points per year more than the market during the same 15-year time period. Either we are electing mavens to Congress who are financially more astute than Warren Buffett or there appears to be some financial rewards associated with being in power.

On the non-pecuniary side, what originally got me interested in the topic of the supply side of politics is when a faculty mentor at Harvard, Joe Kalt, and I were seeking to explain Senate voting behavior on an issue such as coal strip-mining legislation. What was striking to us when we did the study in the 1980s was how little of the senators’ voting behavior could be explained by the demand-side pocketbook interests from their respective states (e.g., coal consumer interests, coal producer interests, environment groups, and so on). Rather, senators appeared to have a great deal of latitude to vote their own ideological interests on particular pieces of legislation. And, while these ideologies varied greatly across senators such as Ted Kennedy and Orin Hatch, their personal, non-pecuniary goals were the most significant explanatory variables by far of their voting behavior.

Mark: In democracies, capture of the state by special interests at the expense of the public interest is often symbiotic and involves both demand- and supply-side special interests. Take the case of sugar import quotas which annually hurt American sugar consumers by $500 million more than they benefit domestic sugar producers in states such as Louisiana and Hawaii. Why do these quotas persist? Certain demand-side groups, namely sugar producers, have more concentrated stakes and thus are more readily mobilized to lobby on behalf of the quotas than do other groups who stand to lose from the quota but whose stakes are much more diffuse. The average American sugar consuming family, for example, has been estimated to lose roughly $50 per year from the quotas and thus doesn’t have much motivation to lobby for eliminating the quotas—even though there are a lot of such families across the country. So, thanks to the political clout of demand-side producer interests coupled with the congressional representatives on the political supply side from sugar-producing states, the quotas remain in place and the United States is worse off, by half a billion dollars on net, per year. And not only has this policy remained in place, but its effects have metastasized as producers of alternatives to sugar such as high fructose corn syrup (HFCS)—who benefit from the fact that sugar import quotas make sugar more expensive in the United States—are now working in tandem to preserve the policy, as are the political representatives from their home states. Archer Daniels Midland, as a producer of HFCS, is a political bedfellow to the sugar-producing Dole Food Company. And Congressional representatives from Illinois (ADM’s home state) are bedfellows on the supply side of politics with congressional representatives from the sugar-producing states of Louisiana and Hawaii.

Elliott: I understand that non-pecuniary effects are important. But one cannot say a priori that these actions are corrupt where corruption is defined as acting dishonestly in return for money or personal gain. I would say the same thing about the huge pension liability. Having politicians "sweep things under the rug" is nothing new but I feel it falls short of corruption.

Mark: While we most often think of corruption as involving bribery, it can also involve personal gains of the nonmonetary, ideological kind that are realized at the expense of the public interest. Hitler, Mao, Stalin, and Pol Pot were motivated more by their ideological goals than their monetary goals. And in seeking to further their own ideological goals they wreaked havoc on their nations. As the eighteenth-century German Romantic poet Friedrich Holderlin observed: “What has made the state a hell on earth has been precisely that man has tried to make it his heaven.”

Elliott: Consider next China and India. I have worked in both countries, and I find them strikingly different. Based on how long China has existed with essentially the same government, it must have been doing something right. India, on the other hand, is a democracy where democracy was imposed by a foreign country – England. Both countries have plenty of corruption but how it affects policy is quite different. In China, the party understands it must please the people to stay in power. So it decides what needs to be done and does it. The party decided the country needed new infrastructure and built it. The corruption came during policy implementation as “payments” were made from project funds. In India, things are quite different. Being a democracy with numerous parties, the government gets very little done as government officials accept bribes for one thing or another. I would argue that India fits Mark’s model: people go into government to get rich.

Mark: In the most recent Transparency International survey of public sector corruption where countries around the globe are ranked on a 0 (perfectly corrupt) to 100 (perfectly clean) point scale, India and China are tied with a score of 40, even though the former is the world’s most populous democracy and the latter the most populous autocracy. Corruption is certainly prevalent in India and has been the focus of the Modi administration. In 2013, 54 percent of surveyed Indians reported having paid a bribe over the past year to access a public service or institution, double the global average.

Notwithstanding its proud history, China also confronts issues of public sector corruption and it has been one of the key issues that President Xi has been focusing on during his administration. Of the 1,271 richest people in China in 2015, more than one in seven were in the Chinese Parliament or on its advisory body. And the eighteen wealthiest delegates had assets which exceeded the combined wealth of all 535 members of the U.S. Congress, then-President Obama and his Cabinet, and all nine members of the Supreme Court. Given the extent to which wealth is embedded in the political process in China, is it any wonder that President Xi has been backsliding on many economic reforms initially set in motion by Deng and that State-Owned Enterprises have appeared to become more insulated, through government means, against domestic as well as international competition?

While China has seen many glory days, it has also had what political theorist Francis Fukuyama terms “the Bad Emperor problem.” For example, from being at the pinnacle of global power and socioeconomic progress in 1500AD, China started to lapse when the Ming dynasty’s emperors and bureaucrats became suspicious of traders, commerce, and overseas forays and began to turn inward.

Elliott: I do think a distinction needs to be made between good and bad corrupt governments. I view China as a having a good corrupt government. By that I mean, they make good policy decisions for the country and the corruption occurs via kickbacks during implementation. I see the US and India as having bad corrupt governments: in these two countries, the special interest groups block good policy - going to war so often, our lousy medical and education systems are three cases where special interest get us away from good policies.

Mark: Political leaders pursuing their ideological goals are capable of promoting the public interest. Witness what Nelson Mandela did to heal the wounds left by apartheid and to thereby better South Africa. Kemal Ataturk did likewise, on many dimensions (with some notable exceptions such as the actions taken against Armenians), for his native Turkey.

While the leaders of China may now broadly be perceived as generally advancing that nation’s public interest, there are some notable downsides to their approach involving compromising civil liberties and protecting large State Owned Enterprises (SOEs) from competition. And we don’t have to go back too many decades to find a time when the Communist Party under Mao was wreaking havoc with the wellbeing of its nation’s citizens. Nobel-prize-winning economist Angus Deaton of Princeton University observed that life expectancy in China began to rise in the mid-1960s “once Mao stopped killing people.” While the average life expectancy in China had been nearly 50 years before Mao’s ascension to power, it had fallen to under 30 years by 1960. It is estimated that as many as 40 million Chinese died over 1960-1962 directly due to Mao’s policies.

Elliott: The Indian model fits a large swath of developing countries. Despite the efforts of some colonialists to create democracies, many countries consisted of tribes (across country boundaries) and it did not take long after the colonialists left before they reverted to tribal governance where military power determines who rules and gets the “spoils.” Many Middle East and African countries have “tribal governments.” I have worked in Africa, and there are several special cases. The Mandela revolution was truly remarkable but the government has since reverted to the tribal model. I was in Ghana when Kwame Nkrumah was ousted. The British-trained military took over. And while they were used to ruling by command without regard to market mechanisms, they were scrupulously honest.

Mark: The latest Transparency International heat map of corruption around the globe bears out your point. Of all the continents, the nations of Africa rate as being the most corrupt when it comes to public sector integrity with a few notable exceptions such as Botswana that scored a 60 on the Transparency International scale.

Elliott: I see Latin America as a somewhat separate case. Most of the countries have the rubric of democratic governance with a history of remarkably corrupt leaders such as Juan Perón in Argentina. I was teaching in Buenos Aires later during the Kirchner’s reign. At that time, there was a general acceptance that the leaders were corrupt and nothing could be done. In Brazil today, the same problem appears to be playing out.

Mark: When visiting my son recently in Buenos Aires and presenting the material in the book to a university audience there, one of the faculty members in attendance noted how naïve we Americans are and how rather anomalous our government is in terms of public sector integrity. According to the faculty member, public sector corruption is the assumed norm in his home country as it is in other Latin American states such as Brazil, Venezuela, Paraguay, and Peru.

Capture of the state by individuals on the supply side of politics such as the Perons, the Kirchners, and Menem goes a long way to explaining why Argentina, a country blessed with abundant natural resources, has languished over the past century in relative terms.

In 1914, Argentina was one of the ten richest nations in the world—ahead of France, Germany, and Italy. Indeed, Argentina at the time was a country rapidly climbing the world’s relative wealth ladder. In the four decades before 1914, Argentina averaged a 6 percent annual growth rate, the longest and most sustained growth rate recorded by any country up to that point in time. Its per capita income was 92 percent of the average across the sixteen richest countries in 1914. Today, its per capita income is only 43 percent of the average across the world’s richest countries. According to the latest Transparency International ranking, Argentina scores 36 on the 0-100 scale of public sector integrity, at least an improvement over the 30 that it earned prior to the new Macri administration and under the Kirchners, but still below Cuba’s score of 47. Under Christina Kirchner in 2014, Argentina ranked 107th in the world for public sector integrity and eighth lowest in the Western Hemisphere.

Elliott: What country has the best form of governance? I would argue for Singapore. With 6 primary ethnic groups, democracy would result in stasis. Instead, Lee Kuan Yew ran it as a benevolent despot for three decades. And unlike almost any other country in the world, government officials are very well paid so corruption payoffs are not as attractive as elsewhere. And this is reflected in its Transparency International score where it ranks as the 7th least corrupt country in the world.

Mark: Singapore is the rare exception of an autocracy that outdoes democracy when it comes to public sector integrity. One of the key findings of my book is that our Founders got it right when it comes to choosing a governance form: on average, democracies have a higher public sector integrity score than do autocracies (47.8 versus 33.1 as of 2014 as measured by Transparency International). That said, government by the people does not ensure government for the people and we cannot be content with the fact that we have a democracy nor that democracy, as a governance form, has been on the rise around the globe over the last two centuries. As of 2014, over a quarter of the world’s democracies had a lower public sector integrity score than the average autocracy.

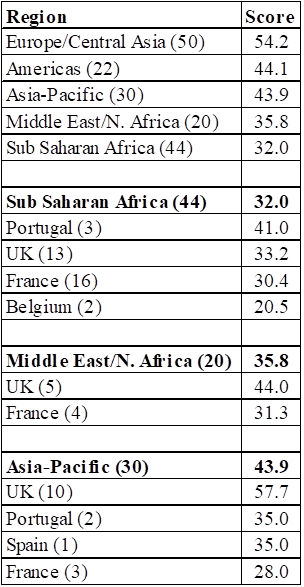

Elliott: One can hypothesize that there have been good and bad colonial regimes, and will affect the degree of corruption today. My sense is that the British worked hard to create professional civil services in their colonies. To test this, I looked at the Transparency International corruption scores for the former Belgian British, French, Spain and Portuguese empires. The findings are presented in Table 2, where the number in parentheses indicates the sample size. At the top of the table, the average corruption scores are given by region (higher scores mean less corruption). The differences are so pronounced that I looked at empires by regions. In Sub Saharan Africa, Portugal has the highest score, but with only 3 countries in the sample (Angola, Cape Verde, and Sao Tome/Principe) the average score should not be taken too seriously. Belgium is a very special case. I have worked in the former Belgian Congo and my sense was that the Belgians spent very little time training the locals. The low scores for Africa overall do suggest that whatever empire they were in, they fell back to traditional modes of governance as soon as the colonialists left. I do think it is notable that for the other regions, the UK had the highest scores, suggesting that my impressions were correct.

Table 2. – Corruption by Region and Past Colonial Regimes

Source: Transparency International

Mark: This is an interesting finding and the preceding evidence clearly supports your hypothesis. Cultural factors have long-lasting impacts. When colonial powers relinquished their formal rule, the impact of the informal cultures that they brought with them to their colonies remained.

Elliott: You mentioned the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA), where it appears corruption has been rampant. I believe the same thing could be said of the Olympics governing body. The people who have been convicted are from countries where being in government as a way to enrich yourself is the norm.

Mark: You are exactly right. Co-opting of the organizational machinery by supply side interests isn’t just a problem in the political sphere. We have also seen it crop up in the broader non-profit arena with organizations such as FIFA, the Olympics, the United Way, the Catholic Church, and universities. A former president at Adelphi University was fired for his spending habits, excessive salary/benefits, and proclivity for taking his board on University-subsidized junkets to Europe.

In the case of the Olympic Committee scandal, moreover, while there were guilty parties from around the globe, I would guess that your hypothesis that individuals from countries with lower Transparency International scores were more likely to be culpable would be confirmed.

Elliott: I checked who was charged or implicated in the corruption scandal surrounding the Olympics in Salt Lake City. Bribe recipients included officials from the following countries (corruption score in parentheses): Chile (66), Ecuador (31), Republic of Congo (20), Sudan (14), Mali (32), Kenya (26), Swaziland (no score). Since Americans paid the bribes, I don’t see in this data set a correlation between country scores and corruption.

I view most developed European countries as similar to the US – relatively little corruption. Incentives are built in to discourage corruption. Russia on the other hand is a special case. The country has little experience with market mechanisms. It appears that in Russia, the best way to make a lot of money is be a good friend of the dictator.

Mark: Under Putin’s rule since 2000, Russia has become increasingly dominated by state-owned and state-supported companies run by “pitertsy,” or St. Petersburg boys. The pitertsy have ties to Putin from either childhood days or from working with him when he was with the head state security unit of the USSR and municipal administration in St. Petersburg.

In Russia, the symbiosis between supply-side and demand-side co-opting of the state is personified by pitertsy government insiders working with crony capitalists outside the government. The wealth of Putin is estimated to be as high as $200 billion. The symbiosis has created such an entrenched power base that it has led to an extremely unequal distribution of wealth. According to a 2013 Credit Suisse report, 110 individuals own 35 percent of Russia’s wealth, the highest level of inequality in the world.

Elliott: You mentioned underfunded pension funds as an example of corruption. I view this as a bit of a red herring. US politicians, as they have done with infrastructure, try to ignore dealing with it. But within the pension fund industry, rampant corruption!

Mark: While I am sure that the cleanliness of the industry can be improved, unfunded liabilities associated with government workers is a growing challenge in our country. Economists Josh Rauh of Stanford and Robert Novy-Marx of the University of Rochester estimate that just the unfunded pension liabilities of state and local workers total nearly $5 trillion dollars and are the nation’s second biggest fiscal challenge—bigger than Social Security while not as large as Medicare/Medicaid/ObamaCare.

Paul Krugman has argued that Detroit’s bankruptcy, largely on account of such unfunded public employee benefit liabilities, was an anomaly. However, I beg to differ with his assessment. We regularly see unfunded benefit liabilities in the news as threatening the finances of states, cities, and territories such as Illinois, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Houston, Dallas, Chicago, Philadelphia, and Puerto. Three cities in California have gone bankrupt in recent years due to such liabilities (San Bernardino, Stockton, and Vallejo). Illinois has not been able to pass a budget for the past three years largely because its unfunded benefit liabilities now total over 450 percent of the state’s annual tax take and policymakers have failed to come up with a means to address the growing problem.

Elliott: I would argue that an informed electorate helps avoid corruption. I view the American public as extremely uninformed on international affairs. And this is a primary reason the military-industrial complex has been able to keep the US at war for so many years. My antidote is to bring back the draft. That way, parents would want to be sure a war made sense before their children went to war.

Mark: Reinstituting the draft would definitely have the benefit of exposing a broader percentage of our citizens to the impact of the military-industrial complex on their lives. The last chapter of my book talks about ways that we can form a more perfect union and thereby ensure that government by the people better aligns with government for the people. Like Dorothy in the movie The Wizard of Oz, we fundamentally, in a democracy, are wearing the red slippers and have it in our power to promote a more perfect union.

One of the important mechanisms to keep in mind is institutions that promote greater transparency in government, such as Transparency International. They have become more numerous in recent decades and the benchmarking evidence that they disseminate is all to the good.

Steve Ballmer, Microsoft’s co-founder, has made some significant personal investments in recent years to promote greater transparency in our government, through his venture, USA Facts. Upon reviewing of the issue, Steve was struck by how little information was available to the average American citizen regarding what actually happens with our tax dollars.

Other mechanisms for improving the integrity of the public sector and ensuring that government by the people also ensures government for the people include: promoting competition in the supply of government goods and services; limiting opportunities, such as through term limits, to hold public position for life; constitutional curbs on public spending and debt such as the debt brake rule instituted by Switzerland in 2003; considering alternative governance forms (presidential democracies, for example, tend to have smaller public sectors and less debt than do parliamentary democracies); and restraining public trusts.

Whereas the unionization rate in the non-agricultural work force of the United States has fallen from 38 percent in the early 1950s to less than 7 percent today, the public sector unionization rate has grown from 10 percent to 36 percent over that same time period. Studies have shown that the growth in this unionization rate in our public sector is a key reason behind unfunded benefit liabilities for state and local workers skyrocketing and educational outcomes in our K-12 public schools being mediocre, at best, notwithstanding an over three-fold increase in real per pupil spending on K-12 public education since 1970.

President Grover Cleveland’ motto was “a public office is a public trust.” While “trust” referred to public officials’ fiduciary responsibility, the growth of public sector union power has altered, in a diametrically opposite way, the manner in which Cleveland’s motto can be interpreted. If anything, we now have to fear the power of public trusts, or combinations in restraint of trade. In the analogy to worries about the marketplace that their private-sector counterparts generated over a century ago, there is a hint of a solution. For the same reason that antitrust statues were enacted to limit the monopoly power that firms in the private sector can exercise to the detriment of consumers, so too can legal limits be placed on the monopoly power that public workers exert, at the expense of citizens, through collective bargaining and lobbying.

Elliott: Mark, thanks for sharing your thoughts on these important issues.