When I was a kid, one of my favorite things to do was grab a random volume of the World Book Encyclopedia, flop down on the couch, and just read random entries (the modern day equivalent of this would be to click the Random Article link in Wikipedia). Some letters of the alphabet were better than others, and a favorite of mine was the “C” volume, since it had an article about computers.

At the start of the article was an illustration of a kid, not much different than me, next to the Empire State Building. The caption said that if there was a computer that was as powerful as the human mind, it would be that big. Although I can see now that World Book was pandering to its audience, I nonetheless always felt a little flattered that I had such a powerful machine in my little cranium.

Years later, I had a real computer – – a reality I never imagined possible as a younger child – – and one of the first programs I bought for my TRS-80 Model I system was Eliza, which was sort of a pretend electronic psychologist. Eliza had actually been created at MIT in the 1960s, and as simple as it was, conversing with it actually seemed pretty natural (and was much cheaper than an actual therapist):

I am reminded of all this since I just finished reading Nick Bostrum’s widely-acclaimed book Superintelligence (it only costs like six bucks, so you might consider getting yourself a copy here). The book, brilliant as it is, does a tremendous amount of hand-wringing about how artificially intelligent machines pose an existential risk to mankind, and how we had better get our act together with respect to these creations to make sure they don’t wipe all of us out.

What I find striking about predictions from technologists is, bluntly, how dumb they can be. Look, I’m no brain trust. These guys have degrees and credentials I could never aspire to possess. And yet, time and again, as smart as these scientists and PhDs are, their prognostications and predictions are so fundamentally empty-headed, that I sometimes wonder if intellect is circular, and once you reach a certain degree of genius, you start orbiting around the “Dumb” mark on the playing board.

Witness, for instance, the obsession with “grey goo” from back in 2000. In case you don’t remember, grey goo was supposed to be nanotechnology gone wild. Countless billions of tiny self-replicating creatures were supposed to consume all the resources of the planet, wiping out the hapless humans that created them in the first place. I want to assure you, twenty years later, that there’s no grey goo in sight, nor is there any meaningful possibility that there will be soon.

Bostrum recounts the history of artificial intelligence (AI), dating back to the fabled Dartmouth conference of 1956. Back then, it was agreed that if a computer could ever play chess against a human, and beat him, then they would achieved the dream of true artificial intelligence. Chess was seen as the apotheosis of the expression of human intellect.

Well, it turns out chess wasn’t so impossible to program, as users of the Sargon II program from the early 1980s can attest. Just because a computer is good at chess doesn’t mean it can think. So, over the years, the definition of what is truly “intelligent” has kept changing. They have a term for it: Human Level Machine Intelligence (HLMI). Presently, over 90% of experts agree that HLMI will be with us by the year 2100.

I’ve been around technology long enough to know that a core problem is extrapolation. People look around what has been going on recently and plot it in a straight line to the future.

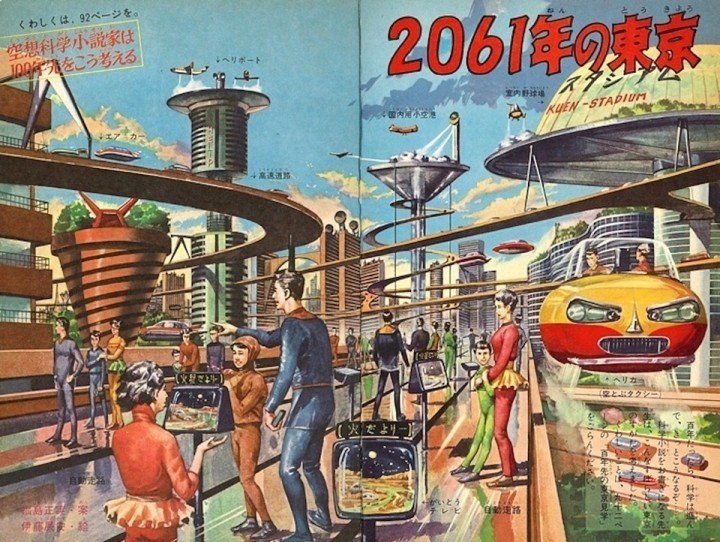

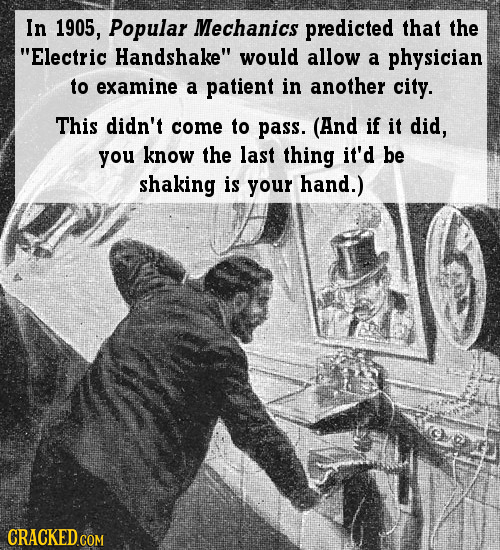

Take nuclear power, for example. In the 1950s, “experts” predicted that everyone’s house would have its own nuclear power plant. And in the next decade, the 1960s, it was all about space exploration. After all, in the span of just a few years, humanity had gone from never having been in space at all (early 1957) to having human beings orbit the earth (1961). So with progress that rapid, we would have Mars colonized by the 1970s, right?

I have GOT to get me one of those skirts.

And yet, here we are, approaching the year 2020, without a man on the moon in nearly half a century. If you told someone in 1962 what the status of space exploration would be in 2020, they would not believe their ears. They would demand to know our accomplishments. And, after we explained Tinder and the Kardashians to them, they would probably beat us to death, and rightly so.

As Superintelligence reveals, the present extrapolation is centered around computers. I’ve been mixed up with computers since 1979, having worked with them practically every day of my life in the past forty years, and I can tell you, I have absolutely zero fear about intelligent, self-aware computers taking over the world and pushing humanity aside. Frankly, the goddamned things barely work as it is, in spite of all the progress we’ve made, and considering we don’t even live in a world where a clean, error-free financial price chart is a reality, I don’t think we have much to fret over.

Besides simple extrapolation, another wrong-headed direction is how it is assumed that the best way to accomplish something a human can accomplish is to create a better version of the human. In other words, to try to mimic how our brains function, but just make it faster.

This is simply on the wrong track. Suppose you were trying to create the world’s first machine to wash dishes. You might ask yourself: how do people wash dishes now? Well, they stand in front of a water-filled sink, brush in hand, and they scrub the gunk off dishes, rinse them, and set them in a rack to dry. So the way to make a dishwasher is to make sort of a six foot tall android that can pick up dishes and scrub them and put them in a rack, too.

Of course, that would be ridiculous, because the cube-shaped object in your kitchen right now – – what nowadays we call “a dishwasher” – – does a superior job, and it bears absolutely no resemblance to any human, Snookie notwithstanding. If you have some specific goal in mind, you don’t necessary have to make a better humanoid in order to accomplish it.

As Bostrum explains it, the first discussions around creating superintelligence focused on what was called “biological cognition”. More specifically, having really smart men and really smart women do the wild thing and create super-smart children. In other words, eugenics. Which is yet another nice idea that Nazis mucked up for all of us. So that was a non-starter.

More advanced ideas of superintelligence have moved away from smart people banging to the more ethereal realm of the man/machine interface. Here, once more, I must bang my head against the wall out of shock that all these PhDs and intellects can be so shamelessly retarded.

There have, to date, been instances of inserting mechanical devices into the human brain out of medical necessity (certainly not for cognitive enhancement). These are very, very tricky, and as simple and specific as their purpose is, they are fraught with side-effects and, to some degree, danger. The notion that someone is going to whip out an RS232-C cable and cram it into a person’s cortex is preposterous, and it simply isn’t going to happen.

Taking it even further, there appears to be the notion amongst some ostensibly tech cognoscenti that they will “upload” themselves to a computer system. Let that sink in a moment. These people actually have accepted the possibility that their memories, their knowledge, and their very soul, can somehow be busted down into a series of 1s and 0s and pushed into a magnetic memory system and, thus, achieve immortality.

Setting aside the hellish prospect of spending all of eternity inside a shaky Windows operating system, let’s all agree that these AI fanatics are out of their minds. In fact, to wrap up this first part of a two-part essay, I present none other than Gilbert Gottfried, who unwittingly offers us an outstanding coda to this thought: