Young Brains, Money And Risk

We know that teens take risks, but we may not know why or that this tendency can continue even to our thirties. This is important for parents who waste much breath—and for growing money, too.

A recent New Yorker article presents the two dominant neuroscience theories for why teens embrace risk. Neurologist Frances Jensen asserts that the electric lines from all over the brain to the frontal lobe are not fully developed until our twenties or even thirties. The frontal lobe is the center of planning, self-awareness, and judgment, so if it doesn’t receive enough impulses, it can’t exercise those functions to override poor decisions. The young aren’t heedless; they simply lack proper wiring.

The second is Laurence Steinberg’s theory that the pleasure center, the nucleus accumbens, grows from childhood to its maximum size in our teens and declines thereafter. Therefore at puberty our dopamine receptors, which signal pleasure, multiply. He says this is why nothing ever feels as good again as when we are teens, whether listening to music, being with friends, or other things not printable in a family newspaper. He maintains that teens are no “worse than their elders at assessing danger. It’s just that the potential rewards seem—and from a neurological standpoint, genuinely are—way greater.” Teen brains balance risk and reward and choose the greater risk for greater potential reward.

But if the young are wired to enjoy now, when the rewards seem greater, they may miss the key element of growing money: time. Money is wet snow rolling down a hill. The money snowball grows larger the longer the hill. Ergo, the younger you are, the longer your hill, the more money you will have.

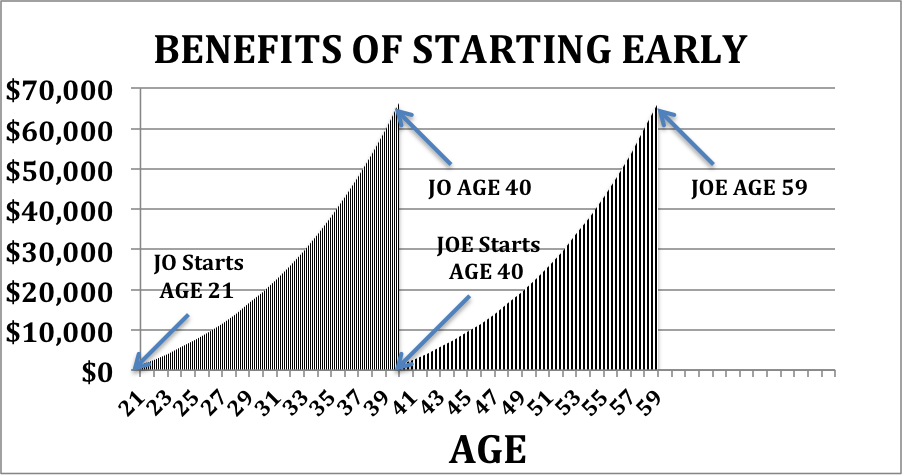

Take Jo and Joe. Each of them saves the same amount but Jo starts at 21 and Joe at 40. Each increases savings each year at the same rate earns the same return. Joe’s savings never catch up to Jo’s; they remain 19 years behind hers forever. In fact, Jo could stop saving and investing at age 40 and Joe wouldn’t have the same amount until he’s 59:

This is an artificial example, of course. There are all sorts of rational reasons for a late start—earning an advanced degree, investing in children, starting a business—but they are ones formed by more developed brains. So because we can see the obvious benefits of time, we must be creative to counter the money decisions of higher risk-taking young brains.

My Dad required me to have a part-time job starting at 15, which eliminated after-school activities. However, he told me that so long as I saved a set amount for college, the rest was mine. That got me over the resentment of missed activities and made me work longer hours, which not only produced spending money but also forced me to manage my scarce time better. Change “college” to any number of savings vehicles, and presto, you have an incentive plan.

Brain science tells us young people take risks because they can’t help it and may miss the benefits of saving and investing earlier. A win-win approach like my wily Dad’s can work wonders.

Tom Jacobs is an Investment Advisor for separately managed accounts with Dallas’s Echelon Investment Management. You may reach him at more

Really enjoy your article.

Excellent article, hope to see more by you. I added you to my follow list.

Love your analogy to wet snow. Your father was a wise man. I've been very concerned about this issue for all those kids fresh out of college who can't find jobs, for all the reasons you state.