While We Wait For The Correction

I am currently inclined to view equity markets through the lens of the ultimate analytical cliché. Prices probably will be higher a year from now, but investors are on thin ice in the near term. I have little other than my gut feeling to go by here. The current situation reminds me a bit of the period before Volmageddon at the beginning of 2018. Even a cursory glance at short-term returns, put/call ratios and deviations from (rising) moving averages raises alarm bells. Claims like this tend to be freebies.

The definition of the “the near term” is unclear, so I can always double down next week if I am wrong. Still, my impression is that most strategists have written their post-rationalisation pieces. After all, if equities corrected by 5%-to-10% over the next month, everyone would solemnly declare that it had been coming. The reason not to expect a correction is that everyone is positioned for one, waiting to buy the dip, but let’s not go down that rabbit hole of circular reasoning.

Whatever happens in the next few weeks to high-flying equities, their general fate still has to be decided in the cross-section between relatively poor fundamentals—weak earnings growth and a soggy global economy—and the ironclad belief in the protection and support of the policy put.

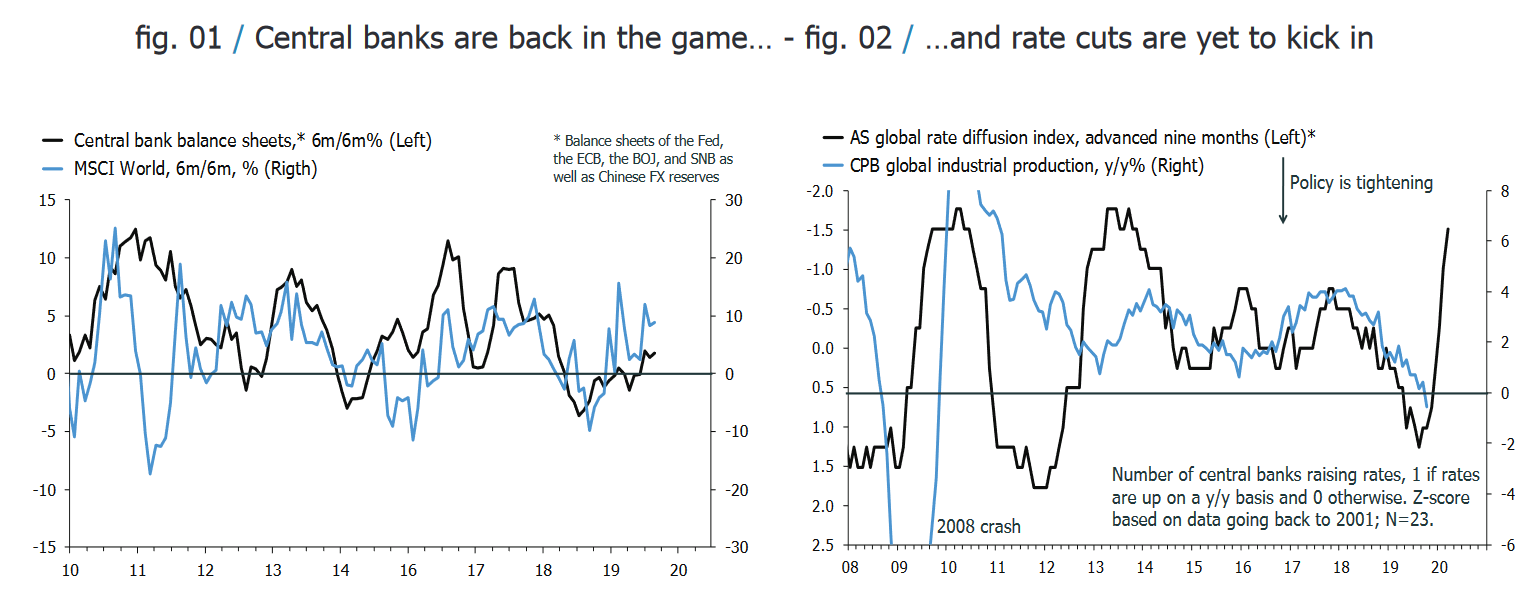

For all the talk about the impotence of monetary policy, last year’s concerted dovish shifts at the Fed and the ECB— with the PBoC and BOJ as silent followers—has been a game-changer. Equity multiples zoomed higher, credit spreads tightened, and yield curve inversions have been vanquished. That doesn’t look like impotence to me, though it’s reasonable to ask who’s running the show? It seems to me that central banks offered investors a finger at the start of 2019, and ended up having to cut off both their arms to deliver as market-based expectations of policy easing ran away with them.

This belief that central banks ultimately will respond to dovish shifts in market-based expectations is just as important as the belief that they’re inclined to ease first, and ask questions later, in response to bad news. They’re two sides of the same coin. In this context, it’s important to re-emphasise exactly what the downside risks are, or perhaps, what they aren’t.

The first-order effects of weak growth, soggy earnings, trade wars and Iranian missiles are comfort-ably dominated by the second-order effects, which is to feed the propensity of policymakers to ease, at least for now.

This point also drives us towards the real downside risks; a shift in policy-makers’ priorities and focus to moral hazard, asset market bubbles and future inflation risks. It’s fair to say that the risk of such a pivot currently is remote, not because the fundamentals wouldn’t allow it. Rather, it’s difficult to expect any of the current key policymakers to turn into the Ghost of Volcker, no matter what the data deliver.

By contrast, I think central banks, and even fiscal policymakers, are now deter-mined to generate inflation, and hence nominal growth, whatever the costs. In rates, this means that the front-end will remain pinned as central banks hope that higher inflation drives up long-rates. Such bear steepening is a good bet for 2020 I think, which, in turn, means that value equities will outperform growth. This should be bit of good news, while we wait for the correction.

*Data for charts are sourced from FRED, OECD, Eurostat, IMF, BIS, Market Watch, Yahoo/Google Finance, COT, Bloomberg, Investing.com or Quandl, unless otherwise stated.

Disclosure: None