The Riddle Of The Dollar

Judging by the latest virus numbers in Europe, and government announcements to contain it, markets may soon have to read up on the math of lockdown economics. Before we get to that, though, investors have been locked in deep thought over the impact of the U.S. presidential elections, which seems to converge on trying to price in the consequences of a Biden victory and a “blue wave”. As I explained last week, investors seem to have concluded that this is a good outcome for risk assets, though as I argued at the time, this isn’t entirely clear to me. To illuminate this further, it’s useful to consider how markets perceive a Blue wave in the context of the dollar and the U.S. bond market. As it turns out, the consensus position isn’t entirely clear, which is a hint. If markets can’t figure out how a Democratic sweep will impact the dollar and bonds, it’s difficult to have any view on how it would impact equities.

The dollar is particularly interesting. It seems to me that analysts initially pinned recent weakness—effectively since April—on the inherent political risks associated with a Biden presidency, though it has since morphed into a bullish catalyst in the context of the expectation of a surge in fiscal stimulus, funded by a benevolent and compliant Fed. Why this latter should necessarily be bearish for the dollar isn’t clear to me, especially not if it led to stronger growth in the U.S. compared to the rest of the world. By contrast, the idea, voiced in some corners of the market, that the U.S. is on its way to print away its exorbitant privilege—in effect losing its reserve currency status—seems even more ludicrous to me, even in a world where China is now Gazelle2299 emerging as a potent adversary. The main source of confusion on this matter is the annoying politically correct narrative on the dollar, and the U.S. economy’s role in the global economy; namely, that the rest of the world— mainly those running external surpluses—are unfairly exploiting the US, stealing everything from intellectual property to US manufacturing jobs. Apparently, this is a wrong that can only be corrected via simultaneously achieving a devaluation of the dollar at the same time as the U.S. maintains its hard and soft power—which is in itself associated with the exorbitant privilege of its currency—or perhaps even increasing it. That doesn’t make any sense whatsoever, but for better or worse, many still seem to be analyzing FX markets through this lens.

The trick is to realize that when it comes to either a weakening or strengthening dollar, we can identify at least four distinct themes, and neither of these are likely to be revealed to markets a priori, especially not in the context of how U.S. bonds and equities respond to a sustained shift in the value of the dollar, and vice versa

1. Weak dollar - > increased valuation in risk assets - It seems to me that this is the scenario the consensus is converging on, or more specifically, the one the consensus prefers. The blue wave becomes reality, fiscal stimulus follows, and the Fed prints to finance it. In such a world, the dollar is debased, but not enough to generate fears over its role as a reserve currency, and in any case, this scenario is also arguably characterized by strengthening domestic demand in the rest of the world, relative to the same in the U.S., driving an adjustment in global current account imbalances. My shout; it won’t happen.

2. Strong dollar - > increased valuation in risk assets - This scenario is similar to number one, with the key exception that as a fiscal and monetary stimulus in the U.S. are unleashed, the rest of the world follows. In other words, if the U.S. creates a lot of dollars, it is effectively lending its exorbitant privilege to the rest of the world—as long as capital flows freely— and the main difference between scenario one and two is the extent to which the rest of the world accepts the invitation. My contention is that the rest of the world will eagerly jump the gun in this regard, in effect printing their own currency in direct proportion to the pace with which the U.S. does it.

3. Weak dollar - > declining valuations in risk assets - This is the scenario in which the U.S. squanders its exorbitant privilege, and global capital decides to go somewhere else.

The main challenge with this story is that we need to figure out where global excess liquidity goes, though we should always remember that sometimes capital and liquidity are destroyed, full stop. Before we get to that, though, markets need to consider the likelihood of at least three self-imposed "wounds” that the blue-wave U.S. might inflict on itself, at least from the point of view of the situation today. The first is a series of tax hikes and/or a political onslaught on wealth and income inequality, the second is an antitrust crusade against big tech, in effect neutering the bull market in Nasdaq, and the third is a leftist version of Peter Navarro’s worldview through which the U.S. becomes an overt and active proponent of capital controls.

4. Strong dollar - > declining valuations in risk assets - This effectively is the point at which Mr. Trump’s #MAGA story runs into its natural limit. In a world of free capital mobility, the U.S. can win the trade wars, but it’ll lose the currency wars, especially if the former is bad for risk assets, which it is, in most cases. In a world where foreigners can buy U.S. assets at will, a leap in risk aversion will tend to drive capital into dollar-based assets, which is the main reason why the politically correct analysis on the dollar noted above doesn’t make much sense. This, in turn, immediately leads to the question of how serious a truly informed and intellectual version of #MAGA and “America First” looks at the question of curbing capital mobility. I am still waiting for an answer.

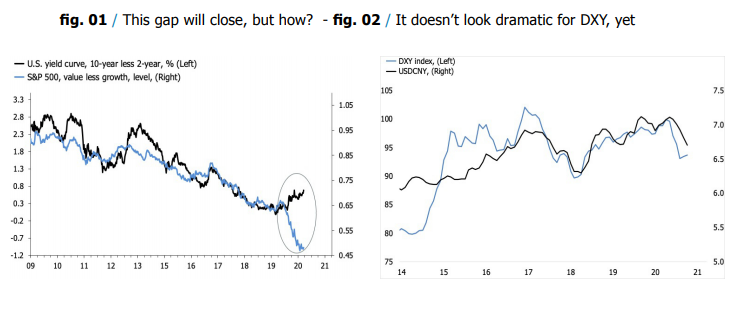

The main point I am getting at is that if we take the performance of risk assets as given, scenario 2 will tend to beat 1, and 4 will tend to beat 3. In this context, the recent decline in USDCNY stands out like a sore thumb, but I think it is easy to explain. Looking beyond the fact that China in some sense is allowing its currency to increase, I’d pin the move in CNY on two trends. The first is the simple macroeconomic reality that consumption of goods has recovered much more solidly than services since lockdowns ended, favoring China as the world’s most foremost industrial power. Indeed, as far as the European numbers go, I’d even argue that the forced decline in services spending seems to have increased demand for goods beyond what we would have expected had economies returned to normal, and stayed there, more quickly. Another element here is that China’s services consumption is mainly tourism—this is to say a drag on the external balance—a “drag” on the currency which has now been reduced significantly. The second driver is that a rally in CNY seems an obvious side-effect of the expectation of a Biden presidency, and a blue wave, simply because of the assumption that a Democratic White House will carry less of a heavy hand in the trade wars. Put simply; markets expect Biden to roll over in the face of China, relative to Trump. I have received a lot of push-back on this point, but it is easily falsifiable in the end. If Biden wins and ramps up the trade rhetoric— which he might well be forced to do—I’d expect USDCNY to rally.

100BP AND NO FURTHER FOR 10Y?

If my story on the dollar seems a bit like the reinvention of the Riddle of the Sphinx, my analysis of the bond market is much more straightforward. The macroeconomics of a blue wave is bearish for long bonds, and as such, the curve should steepen as expectations of such an outcome increase. It has, and will—teasing with the prospect of sustained outperformance in value equities—but the long bond is on a very short leash in the end. `most fixed income analyst I have listened to recently fully expect the 10y to be reined in around 1%. This can happen in one of two ways. Either the Fed announces an explicit yield cap, or it will opt for a revival of the Operation Twist. The main conclusion is simple; the bond market will not be allowed to reflect a fiscally stimulus-driven recovery in a way that we would usually expect early in a cyclical recovery. The Fed is yet to be formally called on the “promise” to put a lid on long yields, but make no mistake, it will eventually, and there will be hell to pay if Powell and his colleagues don’t step up. I suspect they will.

Disclosure: None