The Odd Man Out

It has become increasingly fashionable to direct scorn and ridicule at the so-called equity Perma bears. This is understandable, to a point. These hardened observers and investors have thrown everything at the market, only to see prices go higher almost tick-for-tick with the intensity of their objections. Their curse is increasingly obvious. They can succeed intellectually only if they bite the bullet and buy the very uptrend that they so despise. Alternatively, they can change their mind and embrace the bull market, which would probably have every other investor running for the hills. The market, by implication, would cave in, but they would not be able to claim intellectual victory as those who saw the crash coming, let alone profit from it. Whatever fate awaits the equity bears in this cycle, I am starting to warm to their disposition, at least for the purpose of judging equities in the next six months. As such, while the onus usually, and justifiably, is on the equity bears to explain why it is that the market is compelled to spontaneously combust, the burden of evidence is now increasingly shifting to the bulls. Why is it exactly that global equities are ordained to push ever higher in an environment where fundamentals and other markets suggest that they shouldn’t?

Consider the following story. Growth in the global economy has been slowing in the past 12 months. A weighted average of GDP growth in the U.S., the Eurozone, the U.K. Japan and China averaged 2.2% through 2019, down from 2.9% and 2.7% in 2018 and 2017 respectively. As a result, trailing earnings of global equities are now about 5% lower than at the beginning of 2019. Prices, however, have increased by nearly 28% over the same period, a feat that’s been made possible by a major rerating in the multiple investors are willing to pay for exposure to equities.

I have spent considerable virtual ink on these pages to explain this shift. It is tied to a regime change in monetary, and increasingly, fiscal policy. This theme has been crystallizing since the start of last year, but it now seems fully formed. The idea is simple; not only will policy remain loose for longer, but it will also be used to cap downside risks quicker and more aggressively than before. Even with this in mind, though, the recent performance of global, and especially, U.S. equities is extraordinary.

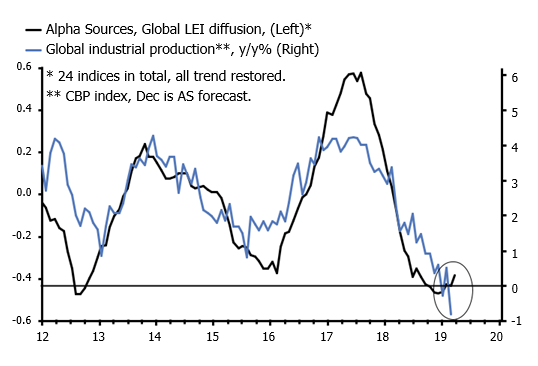

Fig. 01 / The economy, before the coronavirus hit

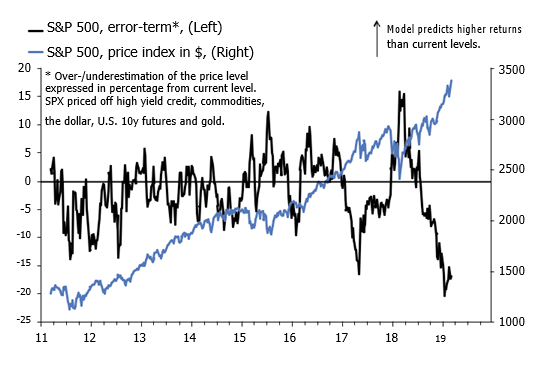

Fig. 02 / Will someone please wake up equities?

Markets entered 2020 with hopes that the worst was over for the ailing global economy—especially in manufacturing— and economists poised to upgrade their growth forecasts. The coronavirus has turned this story on its head. The Q1 numbers are now subject to an abyss of downside risks, linked to the risk that China’s economy literally has ground to a halt in an effort to contain the spread.

Comparisons with SARS in 2003 look deceptively benign until you factor in that the size and scope of China, relative to the global economy, are many magnitudes higher today. In short, global growth forecasts are about to come down, hard, in the next few months.

Some markets already are discounting this. Commodities have been taken to the woodshed, and bond yields have cratered. The U.S. yield curve is once again flirting with inversion along some of the most widely watched spreads, effectively indicating that markets believe the Fed will have to respond. Even the erstwhile docile FX markets have sprung into life. Traders have been selling the currencies most exposed to a further

slump in global trade and manufacturing, in effect translating into dollar strength versus the euro, the Japanese yen and the Chinese yuan.

On the side of equities, meanwhile, the global benchmark briefly sold-off as the coronavirus first hit the news, but it has since motored higher. My previous chart captures this story in a U.S. context; it shows that my APT model now indicates that the S&P 500 is about 20% overvalued relative to other major global assets. The last time my model looked this dire was right before the Volmageddon in Q1 2018, and it eventually took markets a year to work off its overvaluation culminating in a crash in Q4 that year.

I am worried, but it is worth contemplating the idea that resilience in equities is a testament to the strength of the new policy regime. After all, to the extent that the coronavirus is a source of exogenous risk and uncertainty, policy-makers will respond sooner rather than later, so why worry? My old colleagues at Variant Perception offer a fascinating spin on this story. In a recent note, they show that the correlation between fixed income volatility and the term premium is now as negative as it has ever been. In other words, as uncertainty rises the term premium falls, inviting the idea that we are not just living in a world where bad news is good news—via a propensity of policy to ease first and ask questions later—but in a world where uncertainty itself breeds lower rates.

This perspective is fascinating given the sustained outperformance of growth over value, see chart 3 below, and the trend towards ever-tighter credit spreads, no matter the fundamental picture. After all, these two trends are intimately tied to a lower term premium, and a flattening yield curve.

According to research from BoFA, the five largest quintessential U.S. growth stocks now account for 19% of the total S&P 500 market cap, the highest ever. Dwindling net equity supply is also a story—i.e. flows are not driving the rally—but that invites the question of why investors aren’t selling as uncertainty rises. Maybe the answer is that until the story above changes, equities remain the odd man out.

Fig. 03 / Bet against this trend at your peril

Fig. 04 / It even works when de-trended

Disclosure: None