The Fed Mutes The Messenger

U.S. bond investors would do well to remind themselves that the Fed’s objective of stable prices is linked to maximizing employment. They have a twin mandate. In theory these goals are aligned, but not all the time. From 1980-82 the U.S. endured two sharp recessions as interest rates were hiked to vanquish inflation. Today, maximizing employment is the more important of the Fed’s linked goals. They’re willing to take a little risk with inflation, as Fed chair Jay Powell noted last week (see Bond Investors Are Right To Worry).

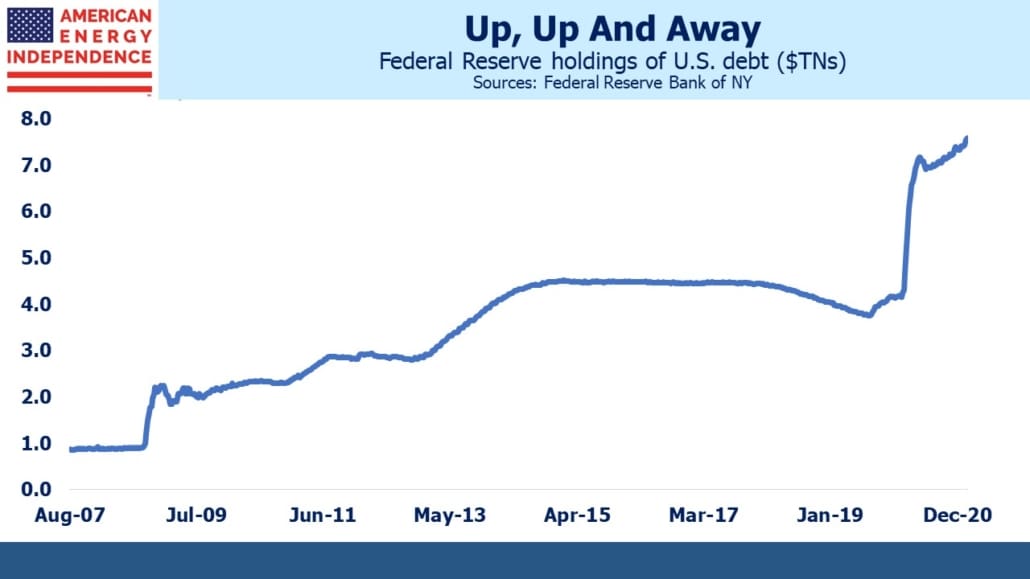

Boosting employment is why the Fed launched Quantitative Easing (QE) during the 2008 financial crisis, to good effect. It turned out that monetizing debt, via the Treasury selling directly to the Fed, wasn’t inflationary. It’s become a permanent fixture. Sluggish improvements in employment meant that the Fed’s balance sheet continued growing until 2014 when it reached $4.5TN. It only began to shrink in 2018. Then COVID hit, and it quickly jumped to $7TN. It’s been growing at $28BN a week for the past three months.

Inflation expectations have been rising at the fastest pace since 2009 as the economy emerged from the last recession. Forward estimates of the five-year inflation rate five years from now (i.e. 2026-31) are around 2%, not yet especially worrying since that’s the Fed’s target.

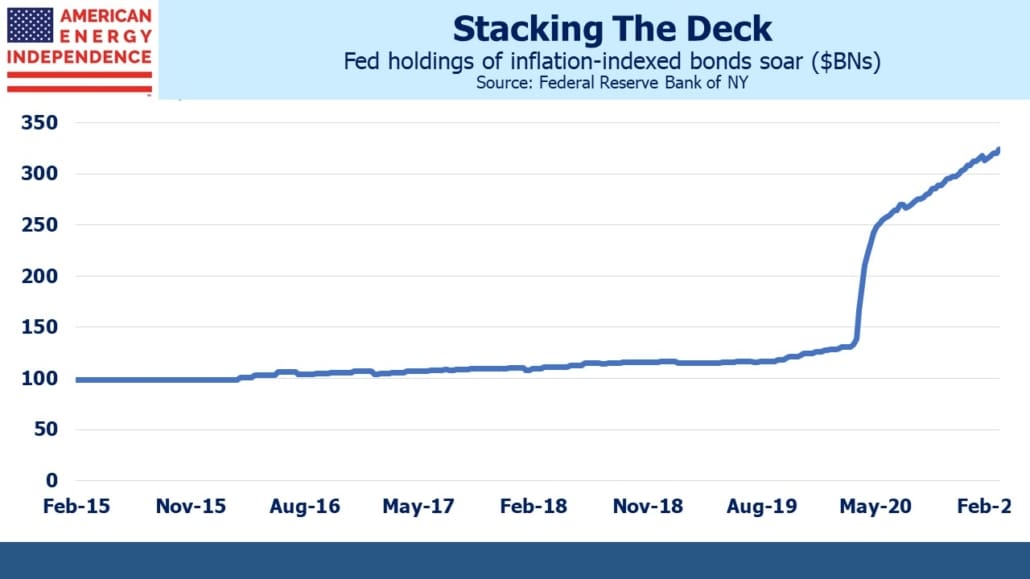

However, such estimates are derived from the yields on inflation-linked and nominal treasury securities. The Fed’s holdings of inflation-linked bonds have risen sharply over the past year, such that they now hold 20% of the outstandings.

This undercuts the Fed’s reliance on market-based measures of inflation – without their sharp increase in holdings, inflation expectations based on TIPs yields would be higher.

Increasing labor force participation by drawing discouraged workers back into the jobs market has gained more attention in recent years, both at the Fed and within Congress. This is no bad thing – it shows the twin mandate with Congressional oversight working.

But in a subtle way, the Fed has been shifting its focus. Inflation isn’t a problem; unemployment is. The returns to bond investors have been a low priority for years, as central banks around the world drove long term rates lower. Now there’s a risk that rising inflation will further erode returns.

Bond yields have been rising globally, reflecting the recovery from the pandemic but also, in the U.S., plans for fiscal profligacy. Central banks don’t like the market message they’re receiving. Australian ten year bond yields have doubled this year, from under 1% in December to almost 2% last week. The Reserve Bank of Australia has acted to counter this trend, recently announcing they’d buy A$3BN of longer-dated debt.

U.S. fixed income markets are communicating an important signal, that a robust recovery is coming. The Fed’s bond buying serves to moderate that message. Yields would clearly be higher, perhaps even affecting the political debate around whether we need $1.9TN in additional COVID relief spending. America’s fiscal response to COVID will reach 25% of GDP as a result, regarded by many as more than sufficient. The Fed is muting the bond market’s response.

QE was originally conceived to extend easy monetary policy out along the yield curve. Yields were falling, but not as far as the Fed desired.

Today’s global yields reveal no shortage of return-insensitive buyers of bonds. In his annual letter published on Saturday, Warren Buffett warned that, “Fixed-income investors worldwide – whether pension funds, insurance companies or retirees – face a bleak future.” QE is evolving to counter the prevailing trend in bond yields – the Fed is rejecting the collective analysis of bond buyers who are demanding higher returns for what they perceive as increased risk. The Fed’s QE isn’t helping these investors. Withdrawing the support will be hard. Watch out if they do.

Protecting portfolios against rising interest rates is hard for most investors. The ETFs that are designed to profit from falling bond prices are very inefficient and costly. Some shelter in bank debt, where their focus on short maturities linked to Libor insulates against rising bond yields. But the underlying issuers are non-investment grade, so this means swapping interest rate risk for credit risk. Interest rate futures are the best choice, but many are put off by the leverage. America’s bifurcated regulatory structure means financial advisors shorting eurodollar futures for clients would then come under CFTC oversight as well as FINRA.

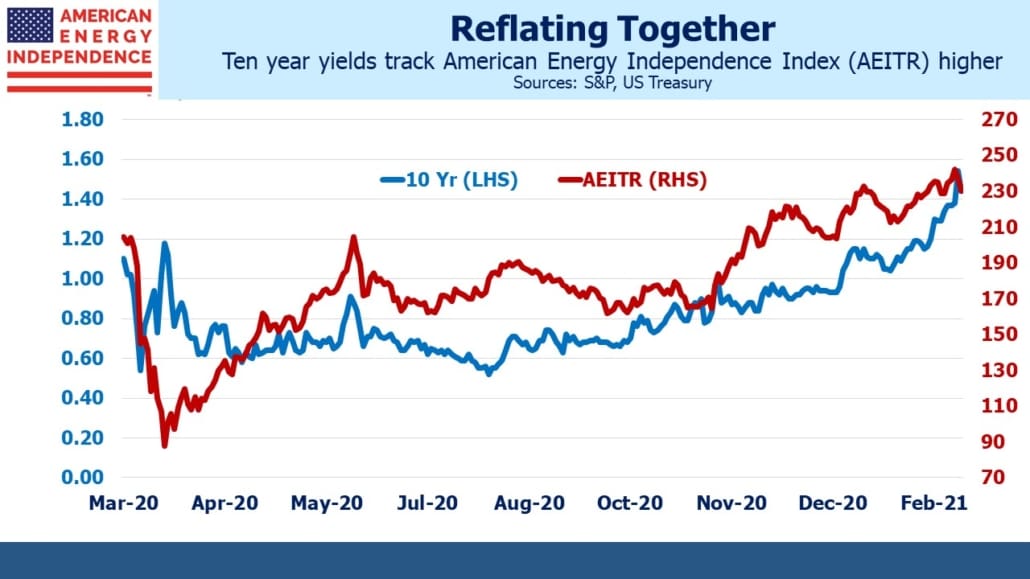

Since the market bottomed almost a year ago, the recovery trade has transitioned into the reflation trade, spurred on by the first vaccine announcement in early November.

Pipeline stocks have tracked the ten year treasury yield higher over the past year, a connection that makes sense since renewed economic activity is driving both higher. Midstream energy infrastructure offers a source of return as rates move higher. It also comes with an attractive yield, something long absent from the bond market.

Disclosure: We are invested in all the components of the American Energy Independence Index via the ETF that ...

more