Stop Obsessing Over Interest Rates

I have a new Mercatus working paper explaining why monetary economics needs to stop focusing on interest rates. Of all the economics papers that I have written, this one best captures how my view of monetary economics differs from the mainstream. Here is the abstract:

In recent years, Keynesians and NeoFisherians have debated whether a low-interest-rate policy is inflationary or disinflationary. Both sides are wrong; interest rates are not a useful indicator of the stance of monetary policy. Some contractionary monetary policies lead to lower interest rates, while other contractionary monetary policies lead to higher interest rates. Instead, economists should use market expectations of inflation, nominal GDP growth, or both to measure the stance of monetary policy. Furthermore, the Fed should no longer target interest rates.

There’s no math because all I really do is use off the shelf concepts like the interest parity condition, Dornbusch overshooting, and the Fisher effect to look at interest rates from a different perspective. I’m not trying to re-invent the wheel, just show that the wheel needs to be re-aligned.

Most economists will probably hate this paper. But if there are a few younger readers that get something out of it, I’ll be happy. Maybe one of them will rewrite the paper using math.

BTW, John Cochrane has a new post that reconciles the Keynesian and NeoFisherian views of interest rates. He suggests that perhaps higher interest rates are disinflationary in the short run and inflationary in the long run—basically Milton Friedman’s view. Here’s Cochrane:

Reconciliation:

In sum, once we include a multitude of plausible fractions that send inflation temporarily the other way, including the long-term bond effect and household financial frictions, a negative response to temporary interest rate rise like Sweden is consistent with a neo-Fisherian prediction that in the very long run higher interest rates produce higher inflation, and thus also consistent with the lack of a spiral at the zero bound.

But I move somewhat in Lars’ [Svensson] direction. Just how relevant is this observation to policy? When the central bank can move interest rates, it may well want to push rates around by exploiting the temporary negative sign. “Temporary” can be a long time. Even if the long-run effect is positive, the central bank may move inflation up more quickly by lowering rates, pushing inflation up with the short-run negative effect, and then then quickly getting on top of inflation. Which is just what central banks classically do, and exactly what they do if the economy is unstable as well. They may never notice the positive possibility, and may never have the patience to wait for it. Thus, the neo-Fisherian possibility may be completely irrelevant in normal times.

But when the central bank cannot lower interest rates, then the slow, preannounced, persistent, we-wont-give-up, and whatever else needed to overcome or wait out temporary forces in the other direction, may still be a useful policy for liftoff. One might indeed read the US interest rate increases — known years in advance — in that light.

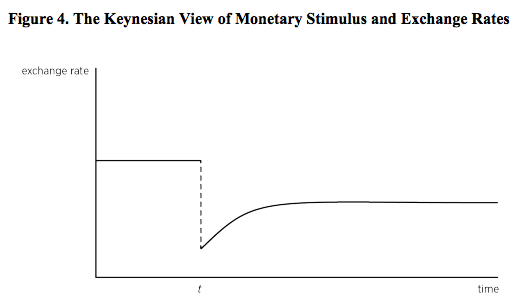

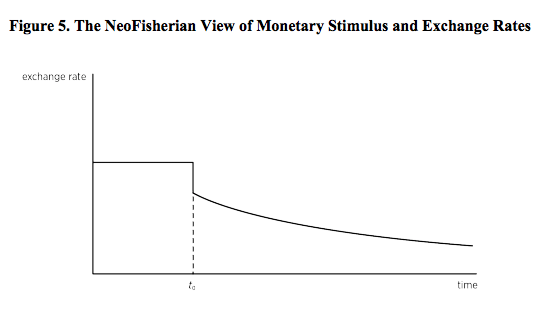

That’s plausible, but it’s not my reconciliation. I believe that monetary stimulus can either raise or lower interest rates even in the short run, as the following two exchange rate graphs illustrate:

PPS. I said most economists will hate my paper. Nick Rowe is one possible exception. Here he comments on Cochrane’s post:

Or setting the exchange rate growth rate. Or setting the TIPS spread. Or setting the NGDP futures price growth rate.

Please, anything but interest rates.