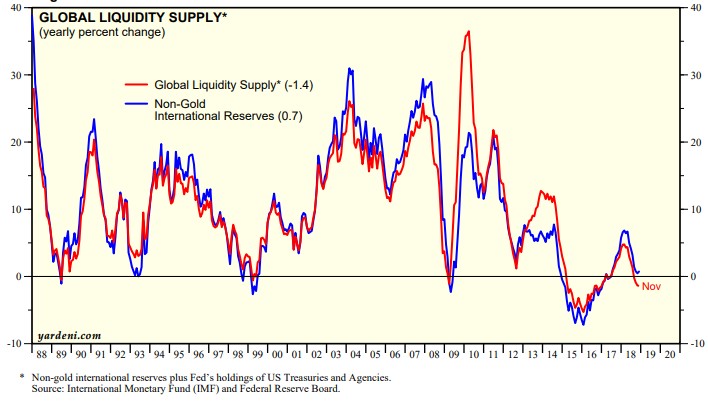

Shrinking Global Liquidity Raises A Red Flag In The Equity Markets

It is a well-established that recessions can be traced back to developments in the capital markets. We recall that the previous two American recessions were caused by excesses in capital spending leading to a misallocation of financial resources which culminated in a very sharp downturn in economic activity. The excess capital going to the dot-com and telecom industries resulted in their eventual collapse and the 2000-01 recession. The misallocation of financial capital in the U.S. housing and mortgage industries had major repercussions worldwide in 2008-9. Despite all the heroic efforts by central banks to re-invigorate economic activity worldwide since 2009, there are no signs of excess capital spending in any particular sector that would be a warning of an impending recession. Yet, there is considerable gloom among investors that a recession is on the horizon and this gloom is seeping into the equity markets.

One of the major concerns is that global liquidity is steadily contracting as the Fed shrinks it’s a balance sheet. Recall that successive bond-buying programs resulted in the Fed’s balance sheet growing from $800 in 2008 to over $4 trillion by 2016. In turn, the monetary base expanded and increasing amounts of liquidity were pumped into the banking system. Now, the Fed is putting this program into reverse. The Fed is leading the way in withdrawing liquidity from the world’s banking systems. Every time it allows a bond to be held to maturity without re-investing, it is removing reserves from the banking system. The withdrawal is currently running at about $50 billion a month. Many analysts liken this “quantitative tightening” to the equivalent of several rate hikes. Recent statements by the Federal Reserve Chairman Powell re-affirms the Fed’s commitment to shrink its balance sheet, thus ensuring further liquidity tightening.

Last month the ECB confirmed that they will stop expanding quantitative easing from the end of December. Bond purchases will fall from 15 billion euros a month to zero. The ECB's asset purchasing program resulted in the bank buying more than 2.6 trillion euros ($2.9 trillion) since March 2015 in a bid to rescue the eurozone economy from deflationary forces.

Source: Yardeni Research, January 10, 2019

What are some of the signs that the decline in liquidity is having an adverse impact on the U.S and world economies? Overall, there is now a clear recognition that economic growth in all the major economies is slowing. Equity markets are skidding since late 2018 as investors downgrade their expectations for profit growth. Companies with high levels of debt depend on liquidity to re-finance and expand operations. The yield curve has flattened in the US Treasury market, a sign that investors do not anticipate inflation reaching or exceeding the targeted 2% figure in the next 3-5 years.

As liquidity become tighter, there has been a sizable drop-off in corporate borrowings from investment grade to junk bonds. Since the 2008 crash, the corporate sector has relied on these borrowings to support investment in new plant and equipment and other business infrastructure. Firms borrowing in the high-yield bond market are also among the most sensitive to changes in financial conditions.

(Click on image to enlarge)

Source: Bloomberg Barclay’s Index

As liquidity everywhere shrinks, corporate bond spreads widen. This makes it much more difficult for new issuers to come to market. A credit spread is the difference in yield between a US Treasury bond and another bond with the same maturity, but with a lower credit rating. If spreads widen, it means investors want more compensation for the risk of lending to a company rather than to the US government. The situation could also be particularly acute for BBB-rated bonds, the lowest-rated bonds on the investment grade spectrum. According to David Rosenberg of Gluskin, Sheff, the biggest risk to the equity markets is widening credit spreads. He rightfully points out that Investors should remember that liquidity tends to dry up in a bear market, especially in the latter part of a credit cycle such as we are experiencing now.

I am listening to Mike Mayonaise Mayo telling us on CNBC that consumer credit is just fine. How does that reconcile with your research, Prof?

My point is that on the corporate side, which means "investment" in the GDP component, money is getting tighter and more expensive. That segment has been increasing debt levels without an commensurate increase in output ( the marginal productivity of capital investment has been falling). We know that the tax cuts did not go into debt reduction or into growing the capital stock--- it was rewarding shareholders. So, the existing debt needs to rolled over and new debt is needed for new investment. Now, the central banks are making matters worse. and that is reflective in the spreads and the deteriorating quality of the lender. Today, Gundlach argued that about half of BBB bonds, the lowest segment of investment grade should be downgraded to junk which tells you how bad is the quality of debt. That would result in more liquidation by funds who cannot hold junk debt. Remember US corporate debt stands at $6 trillion so there is a lot of debt to negotiate out of.

Prof, there is a debate as to whether the Fed is tightening or not. GDP seems to be holding up. My question is whether you think the bad bbb and lower debt is massive enough to reflect that the Fed is indeed tightening, or is it not significant enough to prove tightening?

I am not sure how else one can interpret that sucking out $50b a month as anything other than tightening. Bernanke warned against shrinking the balance sheet until interest rates were ' normal' --presumably much higher than today's because the normal rates would signal that growth was strong and tightening would not slow growth. However, the Fed started that process too early and the equity markets are not suffering from this withdrawal and from trade policies gone amok and China sliding. So, maybe the bad BBB debt is caused by the trade fight or by general slowing. Regardless, withdrawing cash from the system is not helping.