Natural Interest Rate Bleg

I suppose I should know what the natural rate of interest is, given that I’m a monetary economist. But I see the term used in two radically different ways, and am not sure which version is correct:

1. The real interest rate that would exist if the economy were at full employment and stable prices (or on-target inflation).

2. The real interest rate that would be expected to push the economy back to full employment and stable prices (or on-target inflation).

A recent NY Fed piece used the first definition:

The Laubach-Williams (“LW”) and Holston-Laubach-Williams (“HLW”) models provide estimates of the natural rate of interest, or r-star, and related variables. Their approach defines r-star as the real short-term interest rate expected to prevail when an economy is at full strength and inflation is stable.

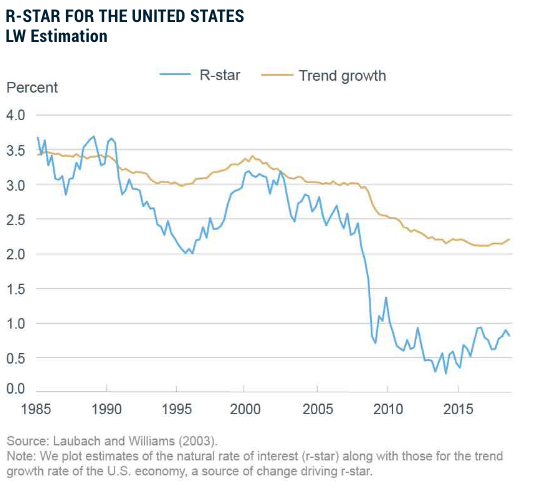

The accompanying graph shows their estimate of the natural real rate for the US:

Obviously, it would have been a disaster if the Fed had set the real rate at that level during the Great Recession. Rather the authors are showing the real rate that would be appropriate in the counterfactual case where the economy was at full employment.

In contrast, an article by Vasco Cúrdia at the San Francisco Fed uses a very different concept when describing the natural rate:

The natural rate of interest is the real, or inflation-adjusted, interest rate that is consistent with an economy at full employment and with stable inflation. If the real interest rate is above (below) the natural rate then monetary conditions are tight (loose) and are likely to lead to underutilization (over-utilization) of resources and inflation below (above) its target.

At first glance, that sounds similar to the New York Fed’s definition, but he later clarifies that this is the rate expected to lead to full employment, and that the natural rate will fall when the economy is depressed:

During the economic recovery, the natural rate was kept low by weak demand due to a larger propensity to save in the aftermath of the financial crisis.

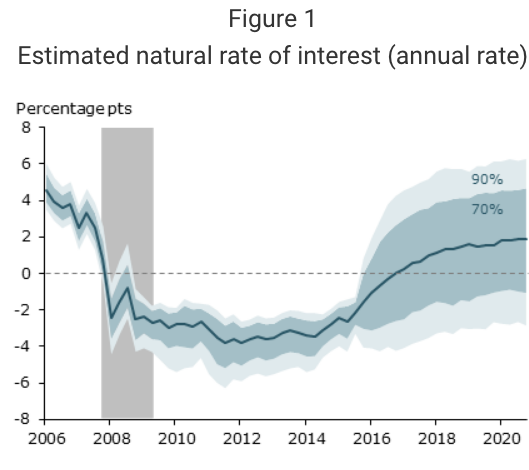

As a result, Cúrdia’s estimate of the natural rate is dramatically lower than the NY Fed estimate:

I like Cúrdia’s definition better, and it’s the one I’ve always used. During the Great Recession, the Fed would have had to initially cut real rates to very low levels to push the economy back to full employment. But if a magic wand (say a quick adjustment of wages and prices by God) had suddenly gotten us back to full employment, then the equilibrium interest rate would be much higher, as is normally the case during booms. That’s the NY Fed estimate.

Alternatively, if monetary policy had been expansionary enough to prevent a Great Recession, the natural rate would not have fallen as sharply.

Here’s the problem. I see each version of the natural rate being used by various economists, and I don’t know which use is conventional. This makes it hard to communicate with other macroeconomists.

Personally, I don’t like speaking Spanish or Keynesianism. But when speaking with Mexicans I at least try to use a bit of Spanish, and when speaking with Keynesians I at least try to use a bit of Keynesianism. But if I don’t know the proper meaning of the terms, then it’s hard to communicate.

Can someone please help me?

Cúrdia explains the difference this way:

Williams (2015) estimates the natural rate to be low by historical standards, but not nearly as low as those shown in Figure 1. The main difference is that Williams uses the statistical model of Laubach and Williams (2003), which is better suited to determine the longer-run level of the natural rate. By contrast, my analysis is suited to find short-term fluctuations in the natural rate.

But that doesn’t seem adequate to me; it seems like they are describing entirely different concepts. And even if it’s correct, it suggests that economists should never refer to the term ‘natural rate of interest’ without first specifying whether it is the short or long run version. Indeed Cúrdia hints at this inadequacy when describing how one could draw incorrect policy implications from the alternative definition:

This distinction is important in evaluating monetary conditions. In contrast to my results, the interest rate gap using the Laubach-Williams measure of the natural rate has been negative since the recession. According to their estimate, the Fed response to the crisis was expansionary because it lowered the real interest rate below its longer-run natural level.

Obviously, if the natural rate is defined as the rate that would prevail if the economy actually were at full employment, it’s of zero value in determining whether monetary policy is expansionary in an economy that is far from full employment. So this isn’t just “semantics”, there are important policy issues at stake here.

Nor can the natural rate of interest be described as the appropriate real interest rate on long-term bonds, as that rate will itself depend on the future path of monetary policy.

Update: Commenter Judge Glock left the following comment, which seems correct to me:

Maybe this isn’t helpful, but I think it just has to do with referring to different parts of the Taylor Rule. For the “long-term” natural rate, people mean the r* as in r* + a1(infl – desired inflation) + a2(output gap – desired output)= i, or, in other words, the intercept of the Taylor Rule, or its equivalent. Other people seem to refer to the natural rate as the final i, the dependent variable of the Taylor Rule, or the output of the equation, which represents the short-term rate when factoring in output and inflation gaps. It may be mere preference or semantics, but it seems to me the i more closely approximates the original Wicksellian understanding of the “natural rate,” or the rate that will keep the economy at equilibrium, while the r* more closely approximates the combination of growth rate and time preference. The confusion, though, could be emerging from the original Laubach-William paper, which, if I’m reading it correctly, estimates the “natural rate” or “r*” by looking at output gaps and real interest rates over time, thus treating the r* as something like the Taylor Rule’s i, even while they also refer to r* as the combination of the economic growth rate and household time preference not dependent on output gaps.