More Energy Discussions In The Palmetto State

COVID introduced us to first-time meetings over Zoom. Last week I had the pleasure of meeting Jack Jeffords and Adam Bloomberg, from Mount Pleasant, SC, in person after having first met them both via a video call several months ago. Recognizing a familiar face along with the person’s voice reinforced how helpful it is to chat on a screen when traveling to a meeting isn’t practical. Like it or not, zoom is now an adjective (although we prefer Microsoft Teams).

Over a convivial lunch reflecting southern hospitality, we chatted about the long term outlook for natural gas, the main focus of our energy investing nowadays. Conveniently, the US Energy Information Administration’s (EIA) International Energy Outlook 2021 (IEO2021) was released the following day. Long term projections such as these are why we’re confident that US pipelines will be in use for decades to come.

As an aside, we learned that port congestion is also an issue at Savannah, with some two dozen ships waiting offshore. Truckers and port warehouse workers are reported to be in short supply.

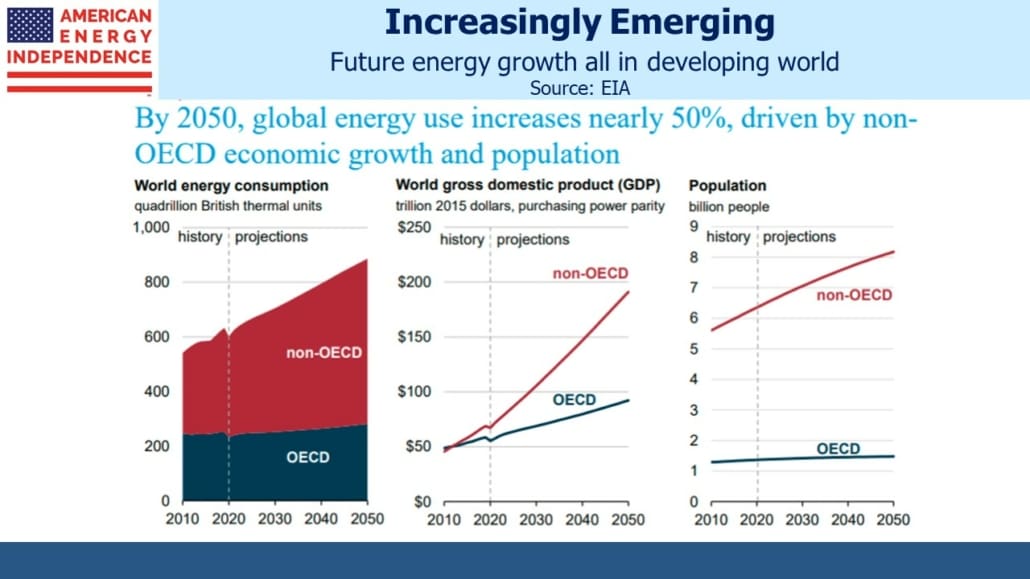

The energy transition brings together two opposing forces – the desire of developed countries (i.e. OECD) to lower emissions, and the intention of emerging countries to raise living standards, which requires increasing their energy use.

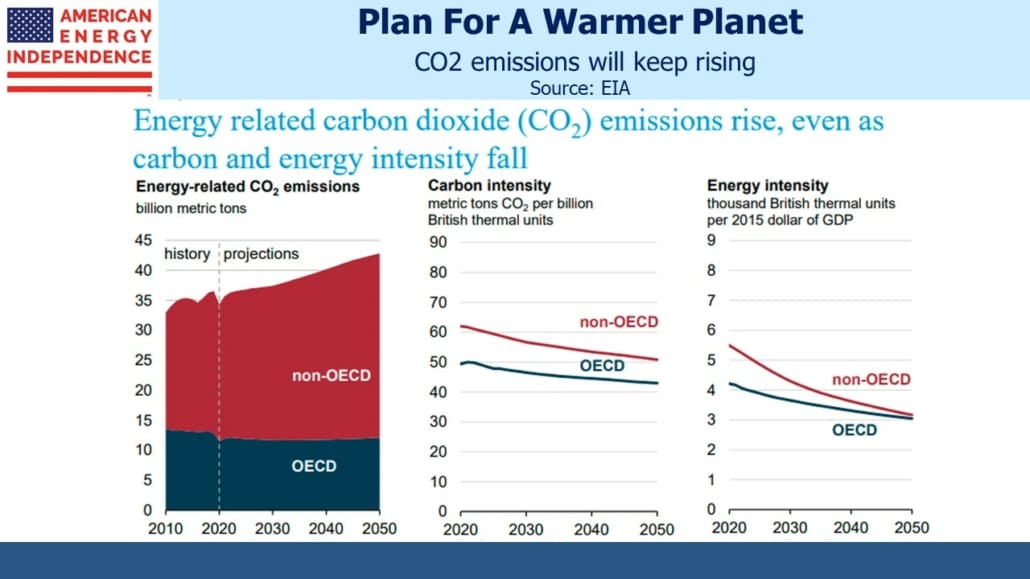

The trajectory of global population and GDP growth means the latter of these conflicting forces will dominate. Even if the US and the rest of the OECD countries cut CO2 emissions in half over the next three decades, the world would still be emitting more CO2 than it does today. The inevitable reality of population growth dictates that emerging economies will drive energy demand for the foreseeable future.

The upcoming COP26 global climate change conference is well timed as it coincides with a developing global energy crisis (ex-USA). This is largely the result of years of policy aimed at dissuading investment in new production of oil and gas, which has directly led to today’s high prices. Europe’s demonstrated vulnerability to supply shortages should inject some overdue humility and realism into the COP26 deliberations (see Europe Follows California Into Renewables Oblivion). They don’t need any more of Greta’s grandstanding.

China has ordered its coal mines to increase output — not good optics for a country that already burns half the world’s coal heading into COP26. India is experiencing blackouts as some of its power stations run out of coal. Energy security supersedes climate change for these countries.

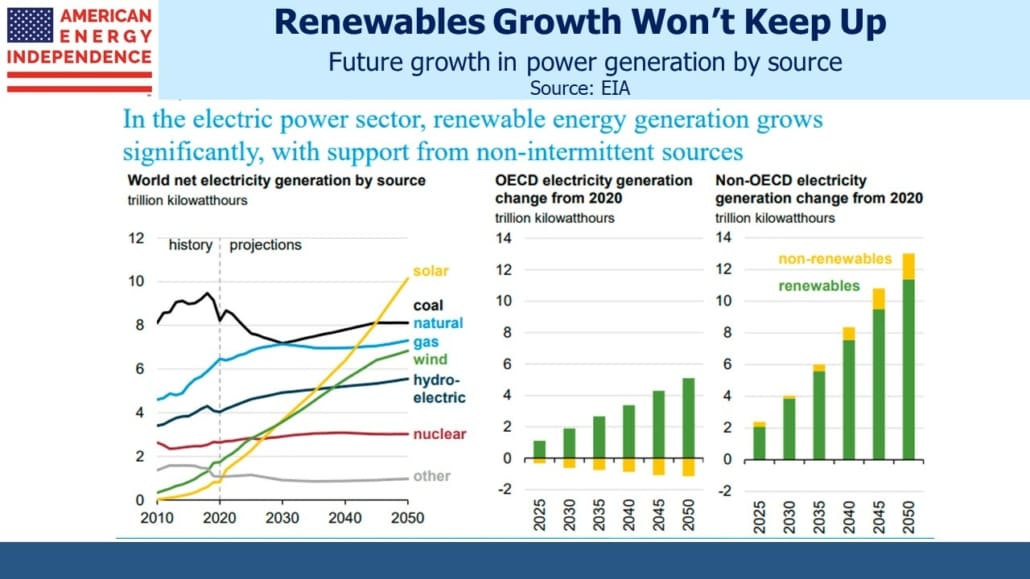

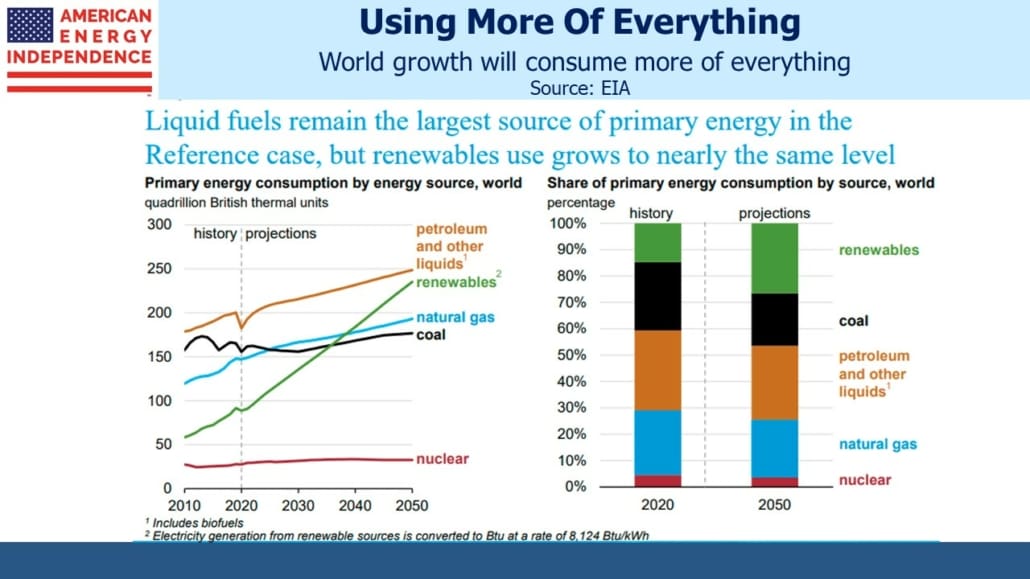

The result is that, for all the relentlessly positive media coverage about increases in solar and wind, renewables will fail to satisfy the growth in world energy demand. Therefore, we’ll be using more of everything – sadly including coal.

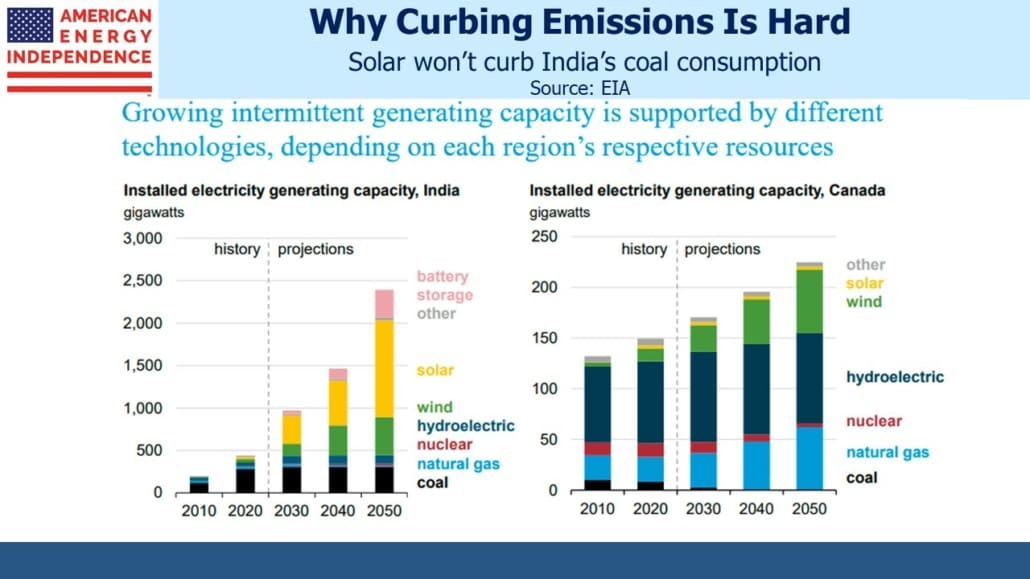

Even in the power sector, which most easily lends itself to increased solar and wind, these two intermittent energy sources will fail to cause a contraction in fossil fuels – in part because increased use of weather-dependent power will necessitate more dispatchable (i.e. there when you need it) sources to compensate for cloudy, windless days.

Perhaps most surprising is the strong outlook for “petroleum and other liquids.” It’s set to grow at 1% p.a. over the next three decades, with growth in every region even including Europe which is farthest ahead on decarbonization. In spite of increasing uptake in electric vehicles, far more conventional automobiles will be bought as living standards rise in emerging economies.

The last chart illustrates the challenge facing policymakers. India’s electricity output is expected to increase five-fold over the next three decades. Enormous increases in solar and wind will still fall short of meeting this growth. This, along with the continued need for conventional power sources to compensate for renewables’ intermittency, explain why India’s coal consumption isn’t likely to fall. Canada’s electricity transmission is on track for zero emissions, but India’s power output is likely to be 10X Canada’s by 2050.

The EIA outlook is based on current policies and technology, which they call their “Reference Case.” The contrast it presents with where most of the world says it wants to go is so jarring that one has to expect some policy changes to come out of the COP26. Nonetheless, it highlights the enormous difficulty the world will have in achieving the IPCC emission goal, which is to reach zero by 2050. The IEO2021 forecasts CO2 emissions going from 34 to 42 Gigatons over that period. We may do better, but zero seems implausible. Given our dependence on energy supplies that work, technologies such as carbon capture will likely become a more important solution, which augurs well for today’s investments in natural gas (UNG).

Disclosure: We are invested in all the components of the American Energy Independence Index via the ETF that ...

more