Magical Thinking

Paul Krugman has a couple of posts criticizing MMT. He tries to be polite, pointing out that at the zero bound their policy recommendations are less bad than those of advocates of austerity. But deep down he must know that this model is sheer madness.

Stephanie Kelton responds and continues the long MMTer tradition of being unable to provide a clear explanation of the ideas. Here she responds to Krugman’s concern that massive deficits might eventually push the public debt so high that interest rates rise to a level that puts a big burden on taxpayers.

First, “there is a devil in the interest rate assumption,” as economist James K. Galbraith has explained. Preventing a doomsday scenario is not difficult. As Galbraith explains, “the prudent policy conclusion is: keep the projected interest rate down.” Or, putting it more crudely, “It’s the Interest Rate, Stupid!”

And just how is the government supposed to “keep the projected interest rate down”? By magic?

Yes, by magic:

Since interest rates are a policy variable, all the Fed has to do is keep the interest rate below the growth rate (i<g) to prevent the ratio from rising indefinitely. As Galbraith says, “there is no need for radical reductions in future spending plans, or for cuts in Social Security or Medicare benefits to achieve this.”

Rather than presenting this as a problem for functional finance, Krugman should be wondering why the Fed would ever maintain an interest rate that would put the debt on an unsustainable trajectory. I don’t believe it would. If i>g, then debt service grows faster than GDP, which Krugman argues would be inflationary.

So his hypothetical scenario begs the question: Why would an inflation-targeting Fed permit i>g with a debt-to-GDP ratio at 300 percent?

Notice that she doesn’t tell us how the Fed is supposed to keep the market interest rate down. It doesn’t just happen by magic. Market interest rates are not a “policy variable”; they are impacted by various policies. While the Fed directly controls the discount rate and the interest rate on reserves, the rates that really matter are market interest rates on public debt. How does the Fed keep them down?

In the short run, the Fed can lower market interest rates (to below the natural rate) via the liquidity effect of an easy money policy. To hold rates down in the long run, you need a very tight money policy, which reduces NGDP growth and thus lowers the natural rate of interest. I kept reading, waiting for an explanation of how the Fed is supposed to keep interest rates down. Easy money in the short run or persistent contractionary demand-side policies? And the answer came in the very next paragraph:

Japan serves as a pretty good example here, with a debt ratio that might well rise to 300 percent one day. Meanwhile, rates sit right where the Bank of Japan sets them, and the government easily sustains its primary deficits.

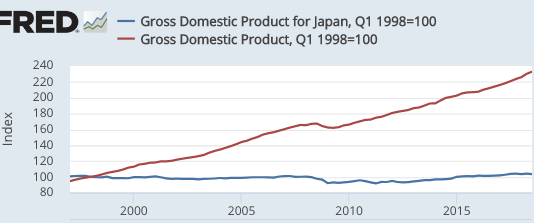

As you may know, over the past 20 years Japan’s had the most contractionary demand-side policy in modern human history, with almost no growth in NGDP since 1998. So the example cited by MMTers as the way to keep rates down is the paradigmatic example of where the action is accomplished through severely depressed spending.

Yes, that will “work”, but don’t MMTers favor boosting demand? I thought they believed that even the US had deficient demand, despite having NGDP growth (red line) far higher than in Japan, even adjusting for population growth.

(Click on image to enlarge)

MMTers seem to believe that policymakers have one more degree of freedom than they actually have. If you want strong growth in spending, you must accept higher nominal interest rates. Otherwise the economy will spiral into hyperinflation.

Second, if we’re so obsessed with debt sustainability, why are we still borrowing? Remember, Lerner didn’t think of borrowing as a financing operation. He saw it as a way to conduct monetary policy – that is, to drain reserves and keep interest rates at some desired rate — as I explained here.

But the Fed no longer relies on bonds (open-market operations) to hit its interest rate target. It just pays interest on reserve balances at the target rate. Why not phase out Treasuries altogether? We could pay off the debt “tomorrow.”

Yes, you can replace all Treasuries with interest bearing reserves, which are simply another form of debt. And that insures that the interest rate you pay is no higher than the “target rate”. But again, if you set the target rate below the natural rate for an extended period you’ll end up with hyperinflation. And no, tax increases don’t prevent high inflation, as we learned in 1968.

What about Japan? Well, Japan pushed their natural interest rate to zero with the most contractionary policy for NGDP growth in all of modern history. Is that their solution? Is that their evidence that there is no natural rate of interest?