Here Come The Taxes

Taxes are going up, but we knew that already.

We have a vague idea what this will look like:

- Marginal rates will go up some. The top tax bracket will go from 37% to 39.6%. There is a chance that another bracket, at a higher level of income, is added after that. The Senate is too closely divided to raise rates more than that.

- The corporate income tax will rise from 21% to something close to 28%. At 28%, our corporate taxes will still be high relative to the global average, but not as high as they were pre-Trump.

- Long-term capital gains taxes will rise for rich people, perhaps by a lot. Biden wants to raise it to 39.6%, which would put capital gains taxes at pretty much the highest levels ever, going back to the late 1970s. It would also turn us all into day traders since there would no longer be a preferential rate for holding investments long term.

And…

I am hearing rumblings that the estate tax threshold will come down a lot, perhaps to estates as small as $3 million. The word on the Street is also that the Yellen Treasury department is taking a hard look at trusts.

Currently, the estate tax affects virtually nobody. But that might not be true for much longer.

I'm not happy about all of this. But relative to how things were shaping up in the Democratic primary—when Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders were proposing massive wealth taxes and income taxes approaching 90%—it could have been a lot worse.

And it still might get worse, depending on what happens after the midterms. (I tend to believe that the Democrats will gain seats.) That's because Biden will have one more crack at changing the tax code.

Before we go any further, let's just say that none of these tax increases have anything to do with deficit reduction. This tax package is supposed to raise $2.1 trillion over 10 years. That's $210 billion a year.

Last year, our deficit was $3.1 trillion, and it will be even larger this year. It doesn't come close to covering the deficit. In fact, if we raised all taxes on every single person to 100%, it wouldn't come close to covering the deficit.

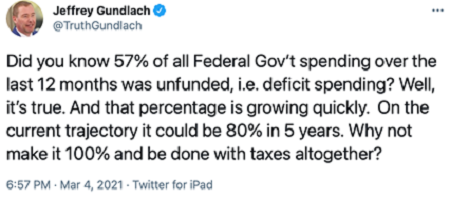

Source: Jeff Gundlach

Jeff Gundlach has made this point a few times on Twitter—tax revenue is now basically incidental to how we finance the government. We spend more than twice what we take in—which means that the deficit is now bigger than the revenue we collect.

We are in a modern monetary theory world, and under MMT, taxes don't really matter. You have taxes for purely ideological reasons. That's about where we are today.

But we should have some conversations on what an optimal tax regime would look like.

I have no political ambitions, but I've always wanted to be a consultant/adviser to a political candidate. Here are my ideas:

The Optimal Tax Regime

Many people have pointed out that the optimal way to raise revenue is through a consumption tax.

Herman Cain had some ideas about this. Other Republican politicians have proposed a consumption tax to go along with significantly lower income taxes.

I'm against this because once parallel tax systems are in place, one day they will both go up simultaneously. This happened in Europe, and now the tax take in Europe is around 40% of GDP, whereas in the US, it is around 20%.

It would take a political upheaval of massive proportions to do away with the income tax entirely, which is why I think we are stuck with it. Best to operate within the framework of the income tax.

The best year for taxation in history was in 1988. That was after the "Tax Reform Act of 1986" (passed under Ronald Reagan), which lowered marginal rates, eliminated deductions, flattened the rate structure, and reduced complexity.

We had only two tax brackets:

- 15% for incomes up to $29,750, and

- 28% for incomes over $29,750.

In inflation-adjusted terms, the 28% tax bracket would kick in at about $85,000 today.

1988 was a pretty good year—let's go back there.

One interesting side effect is that if we went to a 15%/28% rate structure, taxes on the low end would go up… a lot. Especially today, when we are handing out stimulus checks—the effective tax rate on someone making $40,000 a year is about -10%.

Taxes have become more progressive over time—but mostly on the low end.

Mitt Romney inartfully brought this up in 2012—the idea that roughly half the population does not meaningfully contribute to funding the government—and got roundhoused by the media.

My objection to the tax code has less to do with the absolute level of rates, and more to do with the progressivity—the fact that lots of people pay so little (or actually receive money) and some people pay a lot.

Depending on where you go in the country, state, and local tax revenues can be very progressive. The top 1% of taxpayers in California pay roughly half of all taxes… and a mere 65,000 households pay 53% of taxes in New York City.

We're reaching absurd levels of progressivity, and that's even before Biden's proposed tax hikes.

Ain't Gonna Happen

And yet, we keep trending toward more progressivity and more complexity. We even got rid of forms 1040EZ and 1040A.

Trump's 2017 "Tax Reform Act" wasn't perfect, but it was a step in the right direction. But it did not meaningfully lower marginal rates, and it made the tax code even more progressive.

Biden's tax patches won't meaningfully address inequality. The tax hike will hurt working professionals, small business owners, doctors, and dentists while leaving the billionaires relatively unscathed.

Let's go back to 1988. Actually, we just did, with the remake of Coming to America. Although in that case, we should have just left it alone.

We may end up saying the same about the next round of tax reforms.

Disclaimer: The Mauldin Economics website, Yield Shark, Thoughts from the Frontline, Patrick Cox’s Tech Digest, Outside the Box, Over My Shoulder, World Money Analyst, Street Freak, Just One ...

more