Globalization And Inflation Risks

In a globalized American economy, are domestic determinants (e.g., US output gap) the only important factors?

There’s been a lot of talk about how inflation or interest rates will spike due to a collision of fiscal and consumption-driven aggregate demand and diminished potential GDP (perhaps due to scarring, supply chain constraints). I wonder if we are missing part of the issue by using a primarily closed economy model.

I remember 40 years ago, my macro teacher (James Duesenberry) remarking on the imminent collision of fiscal and monetary policy leading to crowding out of domestic investment. Because of the (largely unnoted) internationalization of both goods markets and the liberalization of cross-border financial flows, we got instead (massive) crowding out of net exports.

With that in mind, I consider this 2019 BIS paper by Kristin Forbes:

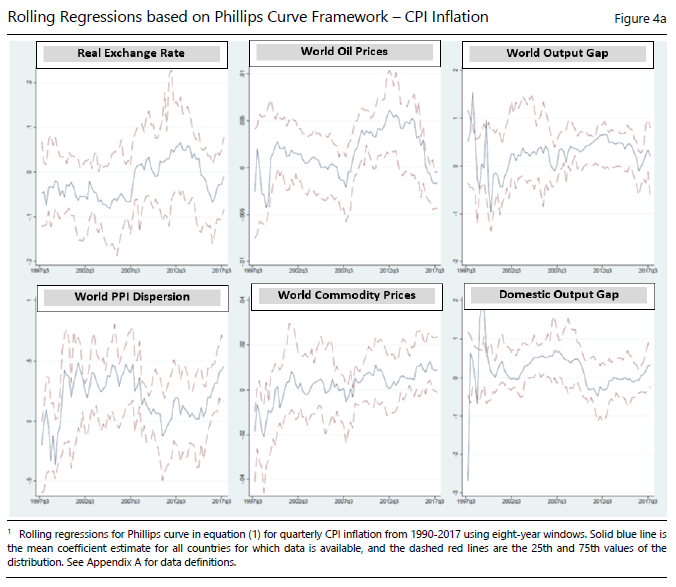

The relationship central to most inflation models, between slack and inflation, seems to have weakened. Do we need a new framework? This paper uses three very different approaches – principal components, a Phillips curve model, and trend-cycle decomposition – to show that inflation models should more explicitly and comprehensively control for changes in the global economy and allow for key parameters to adjust over time. Global factors, such as global commodity prices, global slack, exchange rates, and producer price competition can all significantly affect inflation, even after controlling for the standard domestic variables. The role of these global factors has changed over the last decade, especially the relationship between global slack, commodity prices, and producer price dispersion with CPI inflation and the cyclical component of inflation. The role of different global and domestic factors varies across countries, but as the world has become more integrated through trade and supply chains, global factors should no longer play an ancillary role in models of inflation dynamics.

Using rolling regressions on a panel time-series sample of OECD countries, Forbes finds in the latter half of the period an increased role in the world output gap and a smaller role for the domestic gap (for CPI headline inflation).

Source: Forbes (2019).

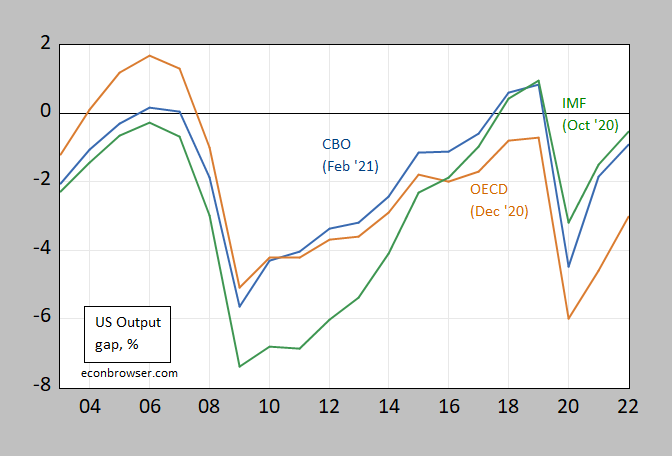

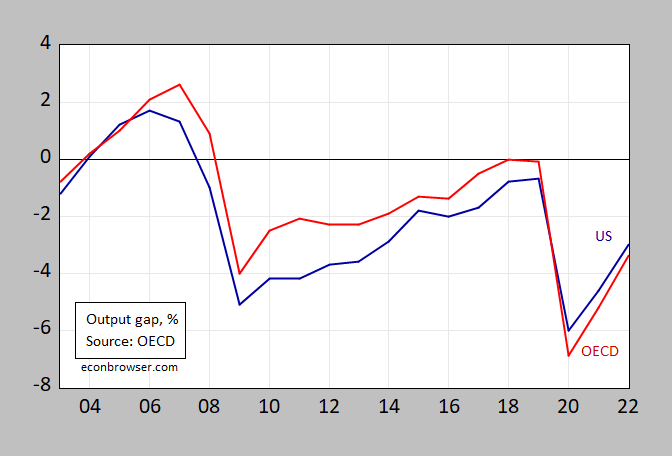

With these results in mind, consider two items: (1) uncertainty regarding the size of the output gap (CBO says it’ll approach zero pretty rapidly, OECD says it’ll be large in absolute value, and persistent), and (2) the sizable OECD-wide output gap.

Figure 1: Output gap, % from CBO (February), IMF (October), and OECD (December). Source: CBO (February 2021), IMF World Economic Outlook database (October 2020), OECD Economic Outlook (December 2020).

Figure 2: US output gap, (blue), OECD (red), in % from OECD. Source: OECD Economic Outlook (December 2020).

Earlier discussion of globalization and inflation, in June 2007, March 2007, May 2006.

Disclosure: None.