Expecting Inflation

Today we’ll consider the arguments for higher inflation in the near future. As you will see, they are serious and convincing. But there are equally serious and convincing points on the deflationary side as well. We’ll get to those next week.

Inflationary Heartbeat

We’ll start with Peter Boockvar. Peter is the CIO at Bleakley Advisory Group and somehow also produces the Boock Report, in which he flash-analyzes the latest economic data in handy bite-size multiple emails per day. In other words, he has as good a finger on the economy’s pulse as anyone I know. And for the last year or so, he’s felt an inflationary heartbeat.

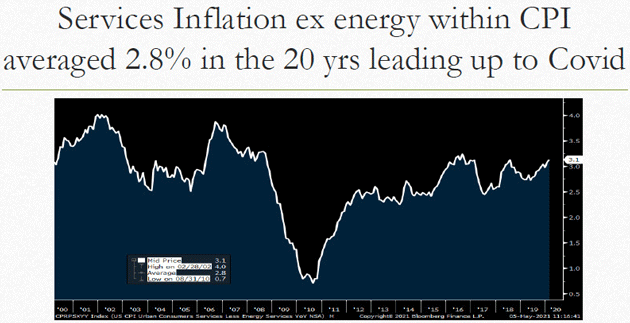

Peter makes an important distinction between goods inflation and services inflation. They have been behaving differently. Looking at services inflation (ex energy) with the Consumer Price Index, he shows it averaged around 2.8% in the 20-year period leading up to the pandemic.

Source: Peter Boockvar

These services are the non-tangible things you can’t put in your pocket but are nonetheless valuable: rent, healthcare, college tuition, insurance, entertainment, etc. Usually we expect their price to rise every year, our only question being how much. Peter’s data says the answer has been around 2.8% a year. Sometimes a bit more or less, but rarely flat and never negative. Take away the Great Recession and the average is much higher. (Of course, your mileage may vary depending where you live.)

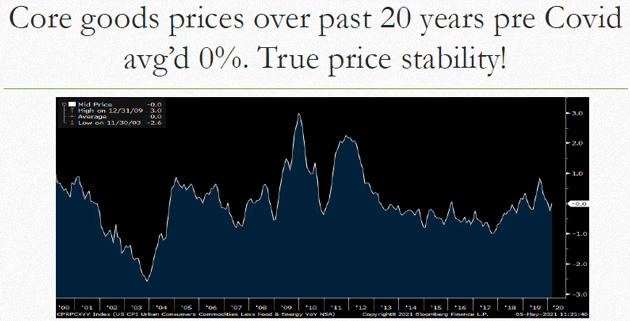

“Goods,” on the other hand, are the material objects and substances we buy in stores, or have shipped to us: food, energy, cars, furniture, toys, lawn mowers, and so on. These prices have more variation than we usually see in services, and often even go down. The 20-year, pre-COVID net, looking at the CPI Core Goods component, was no change at all.

Source: Peter Boockvar

If you never expected to see 0% inflation, now you have. But that’s only in goods; inflation in services pulled the full CPI higher.

How do we explain this discrepancy? We discussed two key factors last week: China and globalization. Goods inflation turned into stability, and often deflation, right about the time China joined the World Trade Organization (2001) and began exporting low-priced goods. But it wasn’t just China; globalized goods production really took off at that point.

Reversal of this strong disinflationary influence is one reason Peter expects inflation. It’s not entirely virus-driven; globalization has been slowing for other reasons. But the pandemic stepped on the brakes even harder. In early 2020 when China basically shut down, we saw how vulnerable these ocean-spanning supply chains can be to events on the other side. Meanwhile, staying home renewed our demand for various physical stuff. If you can’t go to concerts anymore, maybe you buy better home electronics—or a bigger home, which means you (or your contractor) buy more construction material, tools, etc.

Now we see shipping rates and container traffic rising sharply. This isn’t coincidence. The global economy was optimized to deliver something else, and now has to suddenly satisfy new consumer preferences. That drives prices up. Throw in the fact that many transportation companies went bankrupt over the past few years, and the supply of transportation companies all along the supply chain was reduced and thus the prices paid to the survivors have increased.

If services inflation simply continues as it has, and goods inflation rises above the 0% level where it’s been for years, we should expect higher total inflation. But there’s reason to think services inflation will accelerate even more. Buying services really means you’re buying some kind of labor. In a restaurant the food itself costs something, as does the building. But a large part of the bill, maybe most of it, is wages/tips for the cooks, bartenders, and waitstaff. In a hair salon or physician’s office you pay mostly for professional time and skill. There is a close connection between services inflation and wage inflation.

Now look at what happened since last year. The pandemic and its associated restrictions hit the service sector like a neutron bomb. The US government acted, appropriately, to help the millions rendered suddenly jobless. But as often happens, their methods weren’t targeted well. This, combined with the new hazards and hassles of in-person work during a pandemic, reduced the labor supply.

With recovery now underway, employers need workers again and are often having to pay higher wages to get them. That means even more service inflation, on top of the prior 2.8%+ annual growth. Add in new goods inflation and Peter doesn’t see how we avoid a new inflationary cycle. The question is how long will it last?

What Peter and others talk about is what economists call “sticky prices.” Wages are sticky. It is hard to pull back a wage increase. It is not unreasonable to assume that the inflationary forces of rising wages caused by the pandemic and labor shortages will persist.

Demand-Driven Price Hikes

Jim Bianco thinks inflation is already here, and as usual illustrates his point with a series of fascinating charts, some of which I’ll share below. I think Jim mostly agrees with Peter Boockvar but the inflation he foresees is more demand-driven. A lot of people have a lot of spending money and he thinks it will push prices even higher.

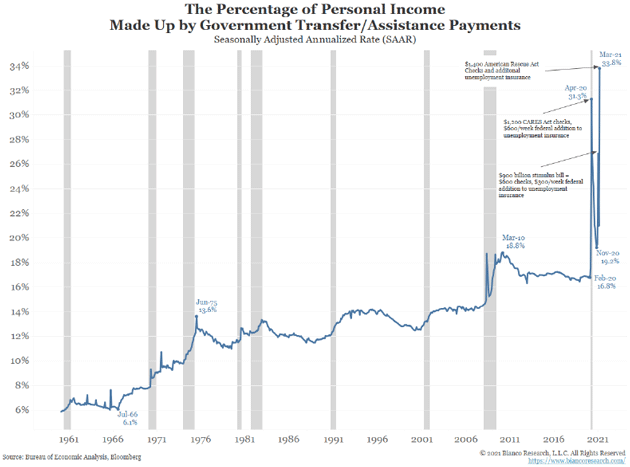

Where did this cash come from? Check out this chart:

Source: Bianco Research

The blue line shows the percentage of personal income that comes from government transfer payments. This includes Social Security, disability benefits, unemployment insurance, and various other programs. It also includes the three pandemic “stimulus” payments send to most American adults. The months those were made pushed this percentage to the peaks you see on the right side. Notice the steep drop after the first stimulus package prior to the even higher peak of the start of the second stimulus wave. Ditto for the third.

These percentages rose not only because the stimulus payments were so huge, but also because wage income had dropped. But the cash stimuli made no such distinction. Everyone got their check, needed or not. So a lot of it went into savings.

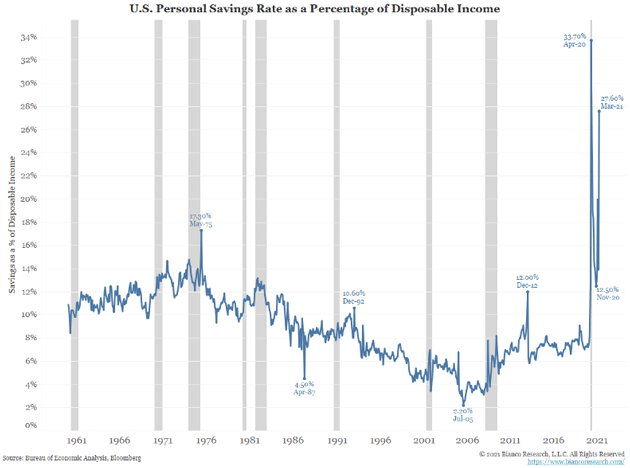

Source: Bianco Research

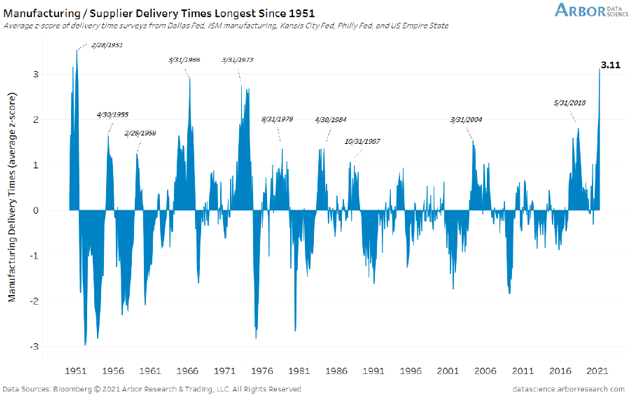

Again, notice the steep drop-off and increase between the first, second, and third stimulus waves. Some of this excess found its way into financial assets, helping stock prices, Bitcoin (BITCOMP), etc. But a lot of it was spent on other goods and services. Jim points to rising demand in a variety of sectors. It is outstripping producers’ ability to deliver, as he shows in this index of delivery times.

Source: Bianco Research

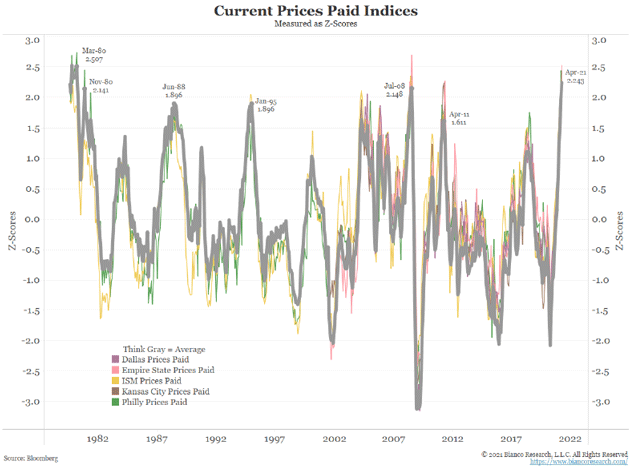

Having to wait for an item you would once have easily found in the store is itself a kind of inflation, even if the price is the same. You get less value than you would by taking it straight home. That’s happening right now and it doesn’t show up in CPI or PCE. But actual prices are rising too. Jim noted it in raw materials, and said finished goods prices should follow. He showed this chart of several price indexes tracked by regional Fed banks. The average (gray line) was last at this level in 1980. Those old enough may recall a little inflation was evident at the time (1980 saw 13.9% inflation).

Source: Bianco Research

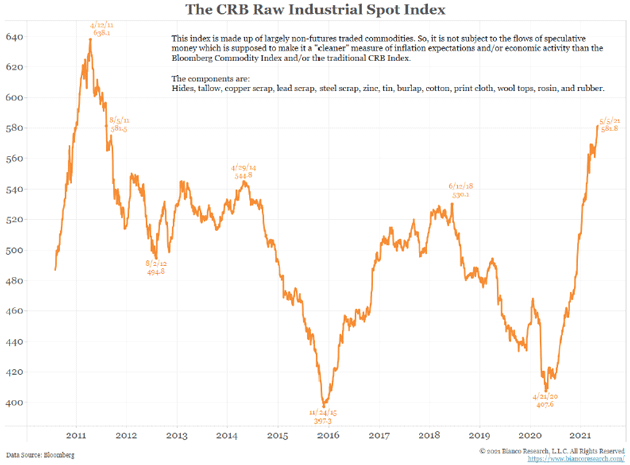

Next, Jim shows this chart of the CRB Raw Industrial Spot Index, which includes copper (JJC) but also several commodities which don’t have associated futures markets: steel scrap, tallow, burlap, print cloth, etc. These are quite important to some key industries and their prices are rising right now.

Source: Bianco Research

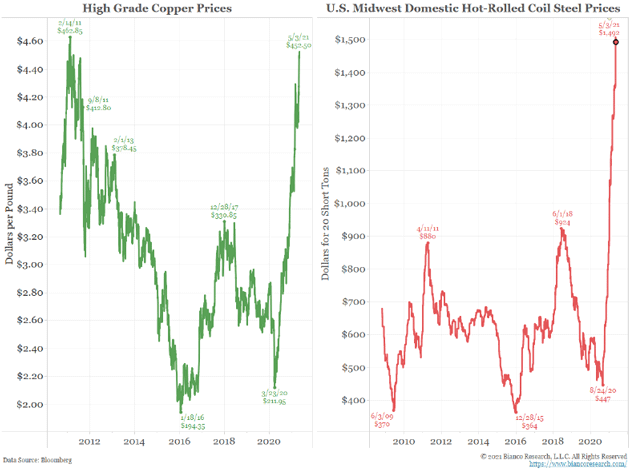

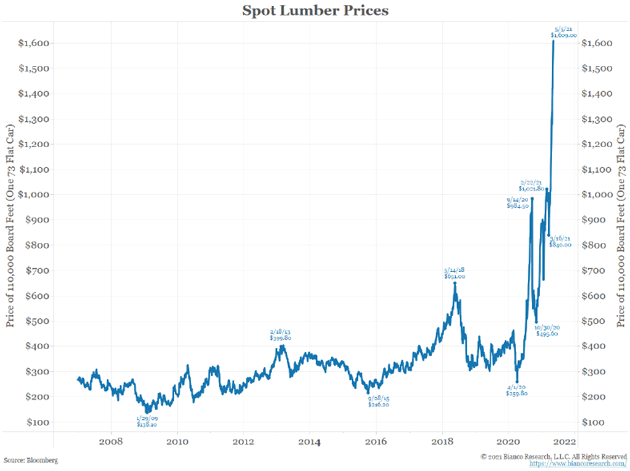

High-grade copper, hot-rolled coil steel, and lumber are all soaring.

Source: Bianco Research

Source: Bianco Research

To be fair, much of this price inflation is due to production closures during the pandemic. Lumber has backed off recently as more supply comes online and high prices deter some buyers. This is why the Fed thinks inflation will be “transitory.” And to some extent, they are correct. But not completely and certainly not in the other elements of inflation.

Source: Business Insider

Jim sums up his view this way. Note: When Jim says “un-anchoring” that is an economic term. Prices over time tend to be “anchored” to prior prices. When prices become generally unanchored, you get inflation.

One-third of everybody's income is now mailed to them from the government. Everybody is stuffed full of money. They're buying stuff like crazy. The supply chain cannot keep up. It is not a problem of COVID, semiconductors. Look, the head of Intel said that the semiconductor supply chain is going to be a problem for two years. There is a simple fix for the supply chain. Charge more money, that's called inflation. What they've done now isn't status, they've rationed the product, delivery times are at a 70-year high, but I think the next step is they're going to charge more money and we're going to get inflation…

But I have a feeling that we're going to find that once the base effect passes, those price increases are going to stick around, people are going to become comfortable raising prices, un-anchoring, and then we're going to have something we haven't seen in a long time and that's inflation. You pretty much have to be over the age of 50, probably over the age of 60 to remember inflation first-hand, it's been such a long period of time. But what I try to show with this is almost every measure says that inflation is coming back and it's coming back with a vengeance.

That’s pretty convincing, but there’s more.

From Energy to Wages

Louis Gave expects inflation for some of the same reasons Peter and Jim mention, he makes an interesting connection with energy, housing, and wages. Briefly, it goes like this.

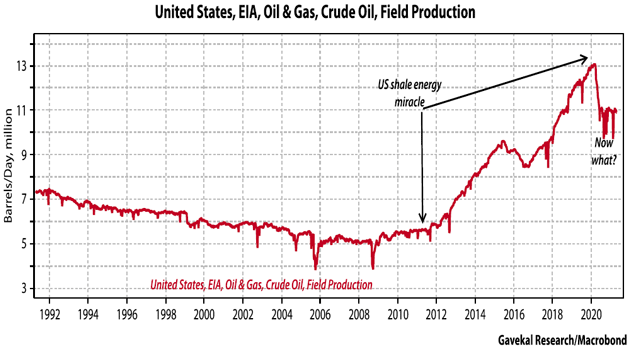

Most economic activity is simply transformed energy of one sort or another. Modern economies developed as we found more efficient energy sources, going from coal to oil to natural gas and nuclear. Now we want to transition from carbon to renewables like solar and wind. This may ultimately bring great benefits, but for now it has produced under-investment in fossil fuel production capacity. US shale production plunged last year and hasn’t yet recovered.

Source: Gavekal

This may be a problem because inventories are low and fuel demand is rising as more people begin moving around again. We can import to make up lost domestic production, but that will add to the trade deficit and weaken the dollar (which is also inflationary). Meanwhile other countries will also be reopening, further increasing global oil demand. This will likely push energy prices significantly higher.

That alone is inflationary, but the follow-on effects may be more so. Rising energy prices will sustain higher housing prices, since construction requires fuel to manufacture and transport large quantities of heavy, bulky building materials.

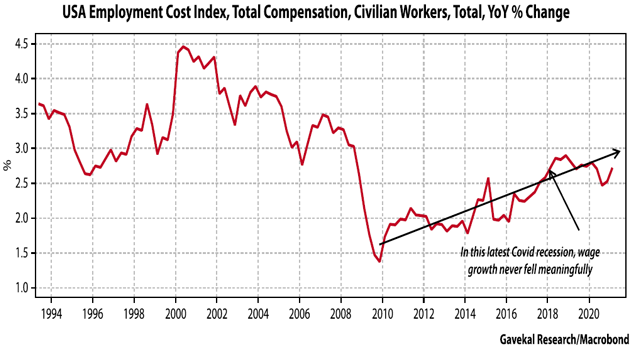

As housing becomes less affordable, wages will have to rise. Prior recessions always saw wage growth slow, if not reverse. We are trying to emerge from a recession in which wage growth never fell, which is historically unprecedented.

Source: Gavekal

You can see in the chart how wages dropped in the 2000 recession and even more obviously in the 2008─2010 period. Note, this doesn’t include the millions who lost jobs and whose wage income fell to zero. In a typical recession, even those who keep their jobs see wages cut or at least don’t get raises. Not so this time. If you weren’t a laid-off service worker, you saw little effect on your pay.

So wages, generally speaking, haven’t dropped and are rising in some segments. You might expect employers to respond with more automation… but we also have a serious microchip shortage. It is reducing automotive production (which raises vehicle prices, further aggravating inflation). Replacing human workers with robots may not be a short-term solution.

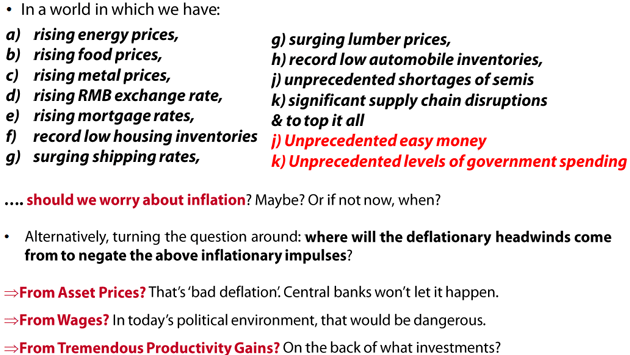

Louis thinks this adds up to a 180-degree change in the economic winds, from deflation to inflation. As he puts it in this chart (read slide two or three times)…

Source: Gavekal

That’s a compelling list… but this story has another side. Deflation may not be as dead as it looks. We’ll consider those arguments next week.

Longtime readers know I have been in the disinflation/deflation camp for decades. Any brief perusal of long-term interest rates and inflation since 1980 demonstrates that was the right position. It was truly self-evident.

But looking at the current inflation data, as we have today, you have to be willing to recognize that all trends, no matter how seemingly inexorable, come to an end. Even the Federal Reserve this week, which has been adamantly protesting that any inflation was transitory and should be ignored, acknowledged in the just-released minutes of their April policy meeting:

"A number of participants suggested that if the economy continued to make rapid progress toward the Committee's goals, it might be appropriate at some point in upcoming meetings to begin discussing a plan for adjusting the pace of asset purchases." (H/T Peter Boockvar)

If I read that correctly, they are going to think about thinking about inflation at some point in the future. Well, I damn well hope so. Announcing a policy of zero interest rates for 30+ months no matter what is the height of insanity. They have no way of knowing the future. What if things change? Remember the days under Bernanke when they said they were “data dependent?”

The Fed’s current policy has painted policymakers in a corner which is fraught with financial repression, destroys the value of savings, hurts retirees, and exacerbates income and wealth disparity, not to mention it helps maintain froth in the mortgage and housing markets which need no help.

Far be it from me to criticize my economic betters, but they risk “losing the narrative” (read: confidence of the markets) and dramatically increasing volatility in all sorts of markets from the unintended consequences of not admitting they don’t know what the future will bring. Why not just stay “data-dependent” (itself a vague, ephemeral notion)? Allowing for the possibility of change if the data changes? (Read me on Twitter for more thoughts on this.)

Disclaimer: The Mauldin Economics website, Yield Shark, Thoughts from the Frontline, Patrick Cox’s Tech Digest, Outside the Box, Over My Shoulder, World Money Analyst, Street Freak, Just One ...

more