Don’t Fear Headlines, Fear Rates

HARVEY IRMA AND KIM DOMINATE HEADLINES

The third quarter was ripe with catastrophe. Hurricane Harvey and Irma made landfall causing significant destruction to Texas and Florida, the second and fourth largest contributors to U.S. GDP. Meanwhile, Kim Jung Un’s continued provocations, including underground nuclear tests and an array of ballistic missile launches over Japan, temporarily roiled international markets. Equity markets remained buoyant, and treasuries garnered their typical flight-to-quality bid as rates fell to their lows for the year. Humanitarian aspects aside (as our hearts go out to those struggling with the aftermath of Harvey and Irma), these events will amount to little more than noise for financial markets. Infrastructure rebuilding generally cancels out the short-term adverse impact of natural disasters, as insurers and governments subsidize the rebuilding process.

VALUATIONS ARE IN THE EYE OF THE BEHOLDER

The number of traders and investors expressing disbelief in the resilience of the equity market is astounding. But why should this surprise anyone? Equity valuations have been overly-extended for years on almost every metric (CAPE ratio, trailing GAAP, forward PE etc.), save one, earnings yields relative to treasury yields. Those managers focused on relative earnings yields have remained tactically overweight to equities much to the liking of their clients. It makes sense that any geo-political event that pushes treasury yields lower would be welcomed by the equity markets.

We have long been proponents of the theory that the principal risk to equity markets is an uptick in yields--one that would nullify the last supportive valuation metric. The implication of this prognosis is paramount to client allocations because it implies that a bond sell-off not only accompanies an equity sell-off, but that it causes it. The everimportant negative correlation between bonds and equities in times of heightened volatility—that managers depend upon--will cease to exist.

There are two necessary preconditions for such a sell-off to occur. One, the Federal Reserve needs to continue to tighten. And two, the market needs to agree with the Fed. The first precondition has been met. The Federal Reserve will likely start tapering its reinvestment program this Fall. And despite market expectations, they will raise in December. The second precondition will not be met until the market stops focusing on the lagging CPI data, and instead focuses on wage growth, the labor shortage, and the deterioration of the global trade paradigm. These are all causal, and will likely drive future inflation higher.

WHY THE FED WILL RAISE IN DECEMBER

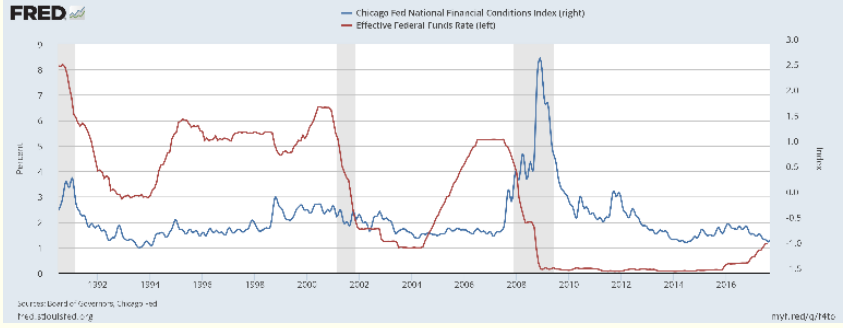

The Fed has already expressed its intention to normalize rates. And despite having raised the Fed Funds target four times since 2015(red line), financial conditions (blue line) are probing the easiest levels since 1994. The Federal Reserve will continue to normalize if the economy and markets allow them. And right now, they are both flashing green lights.

RISK-REWARD FOR LONG-DATED BONDS IS GRIM

I pulled up to an intersection yesterday, and at the corner was a vagrant with a posted sign that read “will take verbal abuse for two dollars.” My initial response was admiration for his creative endeavor to make a buck. While contemplating why anyone would want to endure abuse for a measly two dollars, my thoughts naturally turned, like they often do, to the markets. Why would anyone want to be paid 2% a year for ten years, when the principal value of that capital is likely to be extremely volatile and the purchasing power of that 2% return could very well be less, perhaps much less, in ten years? The absurdity is not limited to the fixed income market. After all, equities are perpetual in nature and based on CAPE valuations (which have very little predictive power in the short-term, but much more accurate in predicting returns over the long-run) investors can expect low-single digit returns over the next ten years. Of course, there is the chance that real interest rates remain negative, and that relative earnings yields on equities remain constructive, and both these asset classes perform as expected. But the risk to this paradigm is high, and growing.

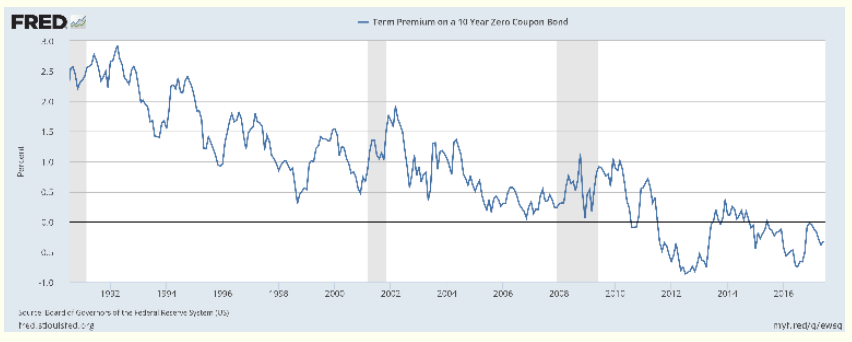

Consider the chart below. The ten-year term premium is a measure of the additional return an investor requires to invest in a ten-year bond rather than continually reinvesting a short-maturity T-Bill for ten years. Term-premiums have been negative for most of the last 5 years meaning investors are paying for the added volatility inherent with a long duration bond. I doubt even the vagrant on the corner would pay me to yell at him. Before 2012, the last time they were negative was the early 1960’s just prior to a multi-decade run-up in rates--food for thought.

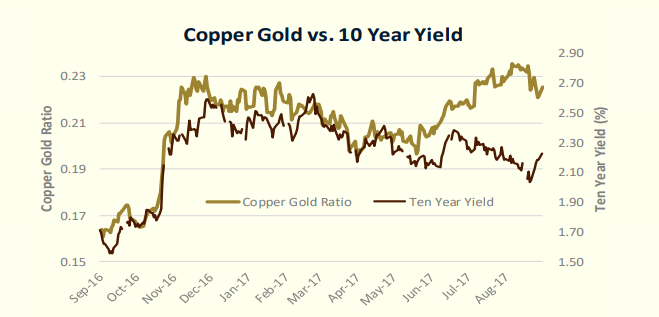

While a reversal of the term-premium trend could likely be a secular story, there are also shorter-term warning signs for treasury investors. The Copper-Gold ratio, which has historically been an accurate barometer for rates has diverged from the ten-year yield.

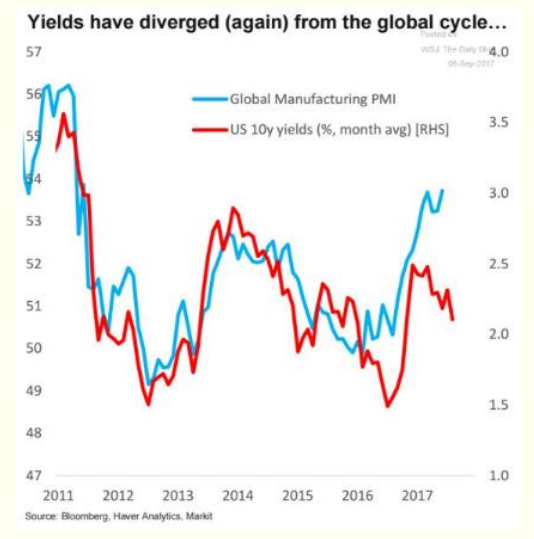

Rates have also diverged from global PMI’s.

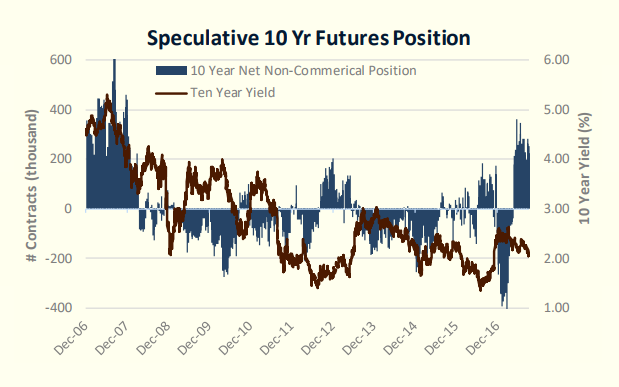

Given these divergences, it seems the recent fall in treasury rates should be attributed to the risk-off reaction to headlines, and will likely reverse absent further geo-political deterioration. Net non-commercial (speculative) long positions in the tenyear futures contract are now the highest since 2007, after an unprecedented swing from a net-short position. These holders are potential sellers if geo-political discord wanes.

THE IMPORTANCE OF DEMOGRAPHICS ON SECULAR TRENDS

Earlier I wrote that yields will not spike until the market focuses on “wage growth, the labor shortage, and the deterioration of the global trade paradigm. These are all causal, and will likely drive future inflation higher.” This statement presupposes that the multi-generational trend of disinflation in advanced economies will reverse. Currently, the popular belief among economists is that the debt overhang in advanced economies, coupled with technological advances will continue to exert downward pressure on wages, inflation, and rates. This is the so-called “newnormal” hypothesis. I have written before, and it is my belief, that this notion is wrong.

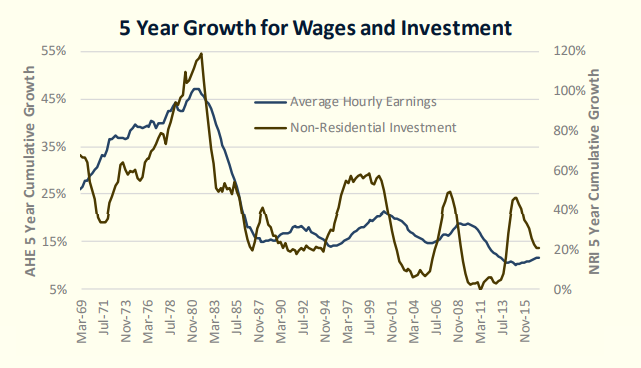

The disinflation experienced in advanced economies is the result of unprecedented growth in labor supply. The influx of the baby-boomers, the integration of women in the workforce, and finally globalization, resulted in a glut in labor, driving wages, inflation, and rates lower. These trends cannot continue, and in many instances, are reversing. The female participation rate is falling. The baby-boomers are retiring, and globalization is facing protectionist political regimes just as the benefits are waning (increased labor supply costs in Emerging Markets). The disinflationary impulse has largely run its course, and economists, Central Banks, and investors are ill-prepared.

The good news is that a reversal of these trends will also improve many of the problems that plague advanced economies. It is no coincidence that as the cost of labor went down relative to the cost of capital, businesses invested less—another multi-decade trend that seems to bewilder economists.

As wages increase, companies will increase capital expenditures and pursue technological innovation. And while this will exert downward pressure on wages in the short-run, history has shown that ultimately, the work force adapts. Productivity will increase, and with it, GDP per capita and the standard of living for many Americans. Inequality, which is at post-war highs, will naturally come down as wages usurp a higher percentage of corporate profits.

Rising dependency ratios come with their own set of challenges--many political in nature. Older cohorts are net consumers while working cohorts are net savers. There will be much political discord over the next few decades as a generational battle ensues between the entrenched political regime—seeking additional transfers, and the up-and-coming producers—seeking to hold onto their rising earnings. The outcome of this political melee will determine much: fiscal deficits, national debt, economic growth, and inflation.

Assuming some semblance of the status-quo persists, we can expect savings rates to continue to fall as the working-age population subsidizes the growing older cohort. This is highly inflationary because transfer payments are non-productive capital. The working-age population can only produce a limited amount of goods, and as their paychecks are transferred to the older generations, by definition, it results in more money chasing fewer goods. Moreover, while the savings glut over the last thirty years has driven real interest rates to historical lows, a reversal of this trend will send real rates higher. For those investors holding thirty-year bonds yielding 2.8%, an increase in real rates and inflation will not bode well.

THE BOTTOM LINE

Dovish Central Bank policy for the last thirty years has been a response to the demographic and globalization impulses that have driven persistent low wage growth, disinflation, low investment spending, and a savings glut. Zero interest rate policy has pushed asset prices higher, including sovereign debt, and global equities. Investors have reaped the benefits, but should recognize that the demographic set-up for the next thirty years may very well support wage growth, higher investment, inflation, and rising rates. Equity and bond markets are much more correlated in the long term than pundits would have you believe. Keep a close eye on rates. And carefully consider what you may have to endure to make your two dollars.

Disclosure: This article is distributed for informational purposes only and should not be considered investment advice or a recommendation of any particular security, strategy or investment product. ...

more