Buying On Margin: Should You Borrow Money To Buy Stocks?

The idea of borrowing money to invest in the stock market can be very appealing for risk-tolerant investors.

Indeed, there are a number of strategies that utilize our ability to borrow money to buy stocks:

- When expected returns are lower than they normally are, borrowing money to buy stocks could juice returns to more satisfactory levels

- Buying high yield stocks with debt whose interest rate is below the stock’s dividend yield can result in higher overall portfolio income

- Similar to #2, buying stocks with expected returns above the cost of debt can boost your total return (not just dividend yield)

On the surface, the return-enhancing capabilities of borrowing money to buy stocks are very appealing. With that said, there are significant risks to buying on margin and borrowing money to borrow stock.

In this article, we discuss the characteristics of margin accounts, the benefits and potential downsides to borrowing money to buy stocks, and three actionable techniques that you can use to invest using a margin account if you so choose.

Characteristics of Margin Accounts

Margin accounts have two important characteristics:

- Interest Rate

- Maintenance Margin/Leverage Limits

We discuss each characteristic in detail below.

Margin Interest Rate

The interest rate of a margin account is the most straightforward characteristic. It is the rate of interest that investors must pay on money that is borrowed within the account.

For example, if an investor deposits $100,000 into a margin account with a 10% interest rate and buys $140,000 of stocks, they would pay $4,000 in interest each year. This is calculated as the total securities owned ($140,000) minus the account’s equity ($100,000, which gives $40,000) and multiplied against the margin interest rate (10% x $40,000 = $4,000). In general, margin account interest is withdrawn from the account each month by the brokerage account provider (such as Fidelity, TD Ameritrade, or Interactive Brokers).

Maintenance Margin

The second characteristic of margin accounts is more nuanced and is a measurement of how much leverage is permitted within the margin account. There are two ways to express these permitted levels of leverage.

The first is by using a term called “maintenance margin”. Maintenance margin is calculated by dividing the minimum required equity by the total security value. If an account has a maintenance margin of 30%, then $3,000 of account equity must be deposited for every $10,000 of securities purchased.

Leverage Limit

The second way to express permitted leverage is by stating a “leverage limit” – which, importantly, is the inverse of maintenance margin and show the possible dollar amount of securities that can be purchased for every $1 of deposited equity. If a margin account has a leverage limit of 4x, then $4 of securities may be purchased for every $1 of deposited equity.

You might be wondering – what happens if your account value declines and you no longer satisfy these permitted margin requirements?

Margin Calls

For most investors, the risk of investing on margin is the probability of experiencing a “margin call”. A margin call occurs when your account equity falls below some acceptable limit that is predetermined by the brokerage company – the maintenance margin that was discussed previously. Like most loans, margin loans require collateral, and when that collateral declines in value, the brokerage company will force you to sell securities to reduce your leverage.

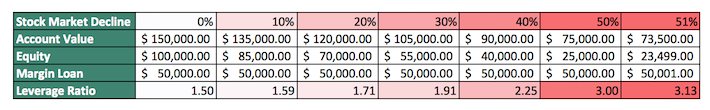

To understand how this is possible, consider the following example:

- Margin account leverage limit of 3x (which means that $1,000 of equity allows for the purchase of $3,000 in securities)

- An investor deposits $100,000 into the account, and purchases $150,000 of securities, giving him a leverage ratio of 1.5x. This is only half of the maximum allowable leverage limit, which ostensibly suggests that the investor has a small probability of experiencing a margin call

- A statistically improbable stock market correction occurs, leaving asset values declining by 50%. Here’s how his equity, debt, and leverage ratio change as the price of his investments fall:

On the surface, it might not be clear why a margin call is a negative occurrence. It has to do with the price of the securities being transacted. Because margin calls are a result of declining securities, they cause you to sell at low prices – which is the opposite of the buy low, sell high mentality that you should be practicing.

Because of the risks of experiencing margin calls, the best way to borrow money to buy stocks is by using debt that is non-callable. Said another way, the best way to avoid margin calls is by making them impossible!

On the surface, it might not be clear how non-callable debt is available to individual investors. Home equity lines of credit are one example, while unsecured amortizing loans are another.

The best example of the use of non-callable debt to buy stocks in the institutional world is Berkshire Hathaway’s (BRK-A) (BRK-B) use of insurance float. The following passage from Berkshire Hathaway’s 2016 Annual Report is helpful to understand the mechanics of leveraged investing using insurance float:

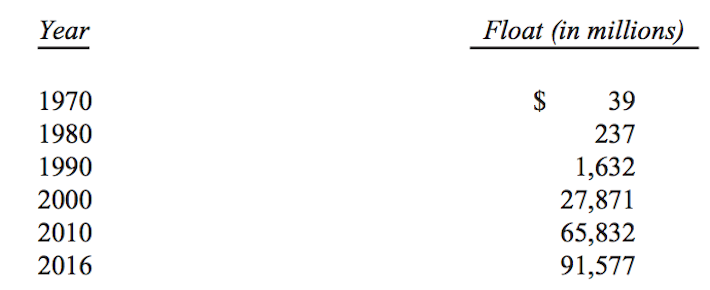

“P/C insurers receive premiums upfront and pay claims later. In extreme cases, such as claims arising from exposure to asbestos, payments can stretch over many decades. This collect-now, pay-later model leaves P/C companies holding large sums – money we call “float” – that will eventually go to others. Meanwhile, insurers get to invest this float for their own benefit. Though individual policies and claims come and go, the amount of float an insurer holds usually remains fairly stable in relation to premium volume. Consequently, as our business grows, so does our float. And how it has grown, as the following table shows:

We recently wrote a huge policy that increased float to more than $100 billion. Beyond that one-time boost, float at GEICO and several of our specialized operations is almost certain to grow at a good clip. National Indemnity’s reinsurance division, however, is party to a number of large run-off contracts whose float is certain to drift downward.

We may in time experience a decline in float. If so, the decline will be very gradual – at the outside no more than 3% in any year. The nature of our insurance contracts is such that we can never be subject to immediate or near-term demands for sums that are of significance to our cash resources. This structure is by design and is a key component in the unequaled financial strength of our insurance companies. It will never be compromised.

If our premiums exceed the total of our expenses and eventual losses, our insurance operation registers an underwriting profit that adds to the investment income the float produces. When such a profit is earned, we enjoy the use of free money – and, better yet, get paid for holding it. Unfortunately, the wish of all insurers to achieve this happy result creates intense competition, so vigorous indeed that it sometimes causes the P/C industry as a whole to operate at a significant underwriting loss. This loss, in effect, is what the industry pays to hold its float. Competitive dynamics almost guarantee that the insurance industry, despite the float income all its companies enjoy, will continue its dismal record of earning subnormal returns on tangible net worth as compared to other American businesses.”

Source: Berkshire Hathaway 2016 Annual Report

While this type of non-callable debt is unavailable to most investors, it is a very powerful way to boost long-run returns in the equity markets. After all, Berkshire Hathaway has grown to a ~$500 billion company employing this strategy! If debt with this characteristic is available to you, then it is most likely to be far superior to buying on margin in the traditional sense.

You now have a solid understanding of the characteristics of a margin account, and the risks associated with experiencing a margin call.

For the remainder of this article, we will discuss three actionable strategies that you can implement inside of a margin account today.

Margin Buying Strategy #1: Boost Equity Returns

Today’s stock market has lower expected returns than most of its history. This is primarily due to low-interest rates, which have pushed valuations higher than their normal levels – and reduced the possibility of future valuation expansion. We have seen the potential outcomes of high valuations in the equity markets recently, as valuations have significant contracted in the second half of 2018.

Indeed, the potential for continued broad-based valuation contraction in the years to come means that forward-looking returns for the stock market are poor. Buying on margin can boost returns, assuming that the cost of debt is lower than the returns that you expect to receive on your investment portfolio.

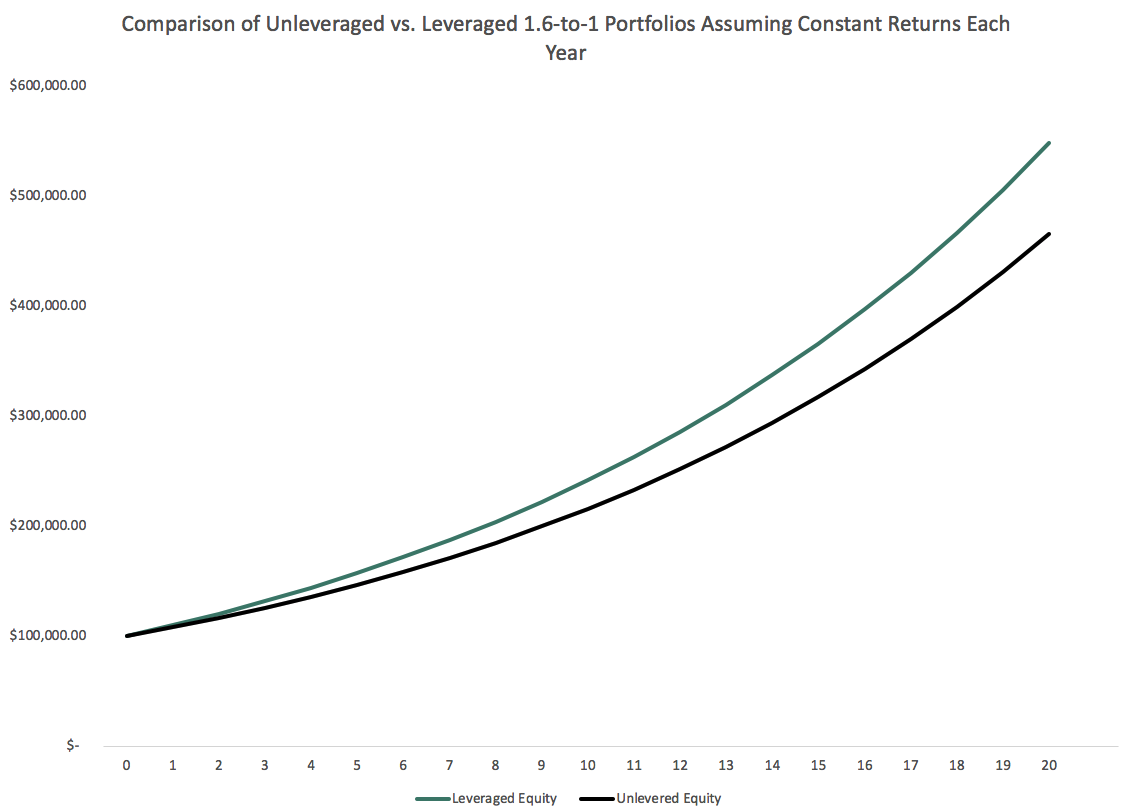

For example, imagine that you invest in a portfolio of stocks that returns 8% per year over a 20-year holding period. While you only have $100,000 to invest, you open a margin account and actually purchase $160,000 of securities. The margin account has an interest rate of 5%.

Here’s a chart of the hypothetical returns of an unlevered portfolio in a ‘normal’ investing account versus the 1.6-to-1.0 leverage that you employed in your margin account.

Source: Sure Dividend Calculations

Note: The returns in this example are unrealistic in practice because the same amount of return is generated each year. In reality, returns are certain to vary from year-to-year, and employing too much leverage could result in a margin call due this variability in returns.

After 20 years, the leveraged portfolio grows to approximately $548,000 while the unleveraged portfolio grows to $466,000 – a difference of approximately $82,000. Clearly, using margin here improved the long-term return available to the investor.

The example above showed a general example of how buying on margin can improve returns. While the example above is generalized, there are generally two specific strategies that investors can use to use borrowed money to boost their equity returns. We discuss each strategy in detail later in this article, beginning with a description of high yield arbitrage in the following section.

Margin Buying Strategy #2: High Yield Arbitrage

For dividend investors, perhaps the most common strategy related to buying on margin is investing in high dividend stocks whose dividend yields are higher than the interest rate of the margin account you’re investing in. Assuming that the company’s dividends stay steady or keep growing, this is an actionable way to increase the income available from your investment portfolio.

An example helps illustrate why this is the case. Let’s use AT&T (T), which is a Dividend Aristocrat with a current dividend yield of 6.9% and is also one of our favorite high yield investment opportunities today. Now, let’s assume that you have $100,000 to invest and you have access to a margin account whose interest rate is 4%. Here are three potential strategies that you could use to increase the yield

- Baseline case: invest $100,000 in AT&T stock and generate $6900 in forward dividend income

- Strategy 1: Invest $110,000 in AT&T stock, which would generate $7590 of forward dividend income and $400 of margin interest expense for net passive income of $7190

- Strategy 2: Invest $150,000 in AT&T stock, which would generate $10,350 in forward dividend income and $2,000 of margin interest expense for net passive income of $8,350

- Strategy 3: Invest $200,000 in AT&T stock, which would generate $13,800 in forward dividend income and $4,000 in margin interest expense for net passive income of $9,800

With each strategy, the investor generates more and more passive income from their $100,000 investment portfolio. However, these strategies are not without their risks. Note that each strategy employs more and more leverage, which means that the investor is exposing themselves to higher probabilities of a margin call. Indeed, the last example, in particular, is unwise for all but the most advanced/professional investors.

Margin Buying Strategy #3: Expected Total Return Arbitrage

Expected total return arbitrage is the strategy of borrowing money to buy stocks whose expected returns are higher than the cost of debt. This is similar to the high yield arbitrage that we discussed previously, except we are betting on the difference between total returns and margin interest, not between the difference between dividend yield and margin interest.

As an example, imagine that you’d like to invest in Johnson & Johnson (JNJ) stock right now, which you believe reasonable expected returns of at least 12% per year over the next 5 years. You believe this to be a reasonably low-risk investment, as Johnson & Johnson is a stable healthcare company and is also a Dividend King with more than 5 decades of consecutive dividend increases. Your margin account has a margin interest rate of 5% and you have $100,000 to invest.

As before, here are several strategies that you could use to take advantage of this expected total return arbitrage:

- Baseline case: invest $100,000 in Johnson & Johnson, which grows to $176,234 in 5 years’ time

- Strategy 1: invest $110,000 in Johnson & Johnson, which grows to $193,858 while incurring $2500 of interest expense for net returns of 12.6% per year

- Strategy 2: invest $150,000 in Johnson & Johnson, which grows to $264,351 while incurring $12,500 of interst expense for net returns of 15.1% per year

- Strategy 3: invest $200,000 in Johnson & Johnson, which grows to $352,468 while incurring $25,000 of margin interest expense for net returns of 17.9% per year.

As before, the more leverage that is employed, the more attractive the strategy appears. Again, though, higher leverage increases the probability of a margin call – which could wipe out many years of stock market gains in severe cases.

Note that expected return arbitrage (or even high yield arbitrage, for that matter) does not necessarily need to be applied to individual stocks. Indeed, buying during recessions is a special form of expected total return arbitrage because during recessions, prices across the entire stock market fall – which leads the whole market to have higher total returns. An investor could potentially take advantage of this by using a margin account to buy broad-based passive ETFs such as the S&P 500 Index ETF (SPY) or the Russell 2000 ETF (IWM).

The Risk of Investing On Margin

As we have discussed ad nauseum in this article, buying on margin has risks. What are those risks?

The largest risk of buying on margin and borrowing money to buy stocks is the potential that you experience a margin call. This will force you to sell at precisely the wrong time, and dramatically impair the returns that are available from your investment portfolio.

Importantly, investors who use margin do not have to be correct about the movement of security prices alone. Instead, they must be correct on both movement and timing. If a stock goes up 100% and you buy it on margin, you are still likely to experience a margin call if it goes down by 50% first.

John Maynard Keynes has an excellent quote on this topic:

“The market can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent.”

– John Maynard Keynes

Because of the risks of experiencing a margin call while investing on margin, we recommend that investors avoid it unless three criteria can be satisfied:

- The interest rate available on margin debt is sufficiently low

- The debt is either non-callable or used in prudent amounts so that margin calls are avoided

- The investor is knowledgeable about investing and has high conviction with respect to the investment idea they’re leveraging

Final Thoughts

In this article, we explained three actionable strategies that investors can use to potentially increase their investment performance by buying on margin. These strategies are:

- Boost equity returns

- High yield arbitrage

- Expected total return arbitrage

In the end, the main conclusion of this article is that margin should only be used in moderate magnitudes by very sophisticated investors that have a high degree of certainty in the investment decisions that they are making.

In addition, when buying on margin is employed as a strategy, it should only be done when the debt it available on attractive terms and only in modest amounts to minimize the probability of a margin call.

Otherwise, the risks associated with buying on margin are simply too great, and we would recommend against borrowing money to buy stocks.

Disclaimer: Sure Dividend is published as an information service. It includes opinions as to buying, selling and holding various stocks and other securities. However, the publishers of Sure ...

more