Brace For (Recession) Impact

The strange recession we are now entering is strange for another reason beside those I described last week. The last “normal” recession ended in 2009, almost 13 years ago. As with most unpleasant experiences, we don’t put a lot of energy into remembering what it was like.

The problem is we need to remember it in order to prepare for the next one, which is now upon us. Today we’ll remind ourselves of what happens in a typical recession, both to the economy and the financial markets. We’ll also look at some of the ways this one probably won’t be typical. It certainly has the potential to be worse.

This week saw some volatility (the good kind) as stock prices recovered and oil retreated a bit. The basic facts haven’t changed, though. Recession was already a strong possibility even before the shooting started - and the genie is out of the bottle even if the shooting stops. The Russian sanctions will continue, which means the global realignment will continue, too.

Another factor is China’s growing COVID-19 outbreak, which is already closing some factories and may lead to more supply chain snarls. Some interpret this bullishly, thinking a China slowdown will reduce energy and commodity prices. That may be correct, but not for more than a few weeks. We face recessionary forces that are much harder to suppress.

Really, I can only imagine one scenario that would make all this better. That would be if Vladimir Putin loses power and is replaced by someone of a sharply different philosophy and that person quickly leads Russia in a new, more democratic direction. Then the war and sanctions could end and Russian exports resume. Possible? Yes. But not likely.

That being the case, recession is where we are headed. So let’s review what it will be like.

"A Significant Decline"

According to the National Bureau of Economic Research, the referee of such things, a recession is “a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months.” That’s as good a definition as any, but it still leaves room for interpretation. What is “significant?” How many months are “a few?”

My friends at Investopedia point to four specific markers of recession:

- Loss of jobs.

- Declining real income.

- Production and manufacturing slowdown.

- Lower consumer spending.

All those are bad individually and even worse together. If they persist for months then I, for one, would call it a recession. Remember, though, this will be a strange recession. It doesn’t have the normal causes and may not have the normal effects.

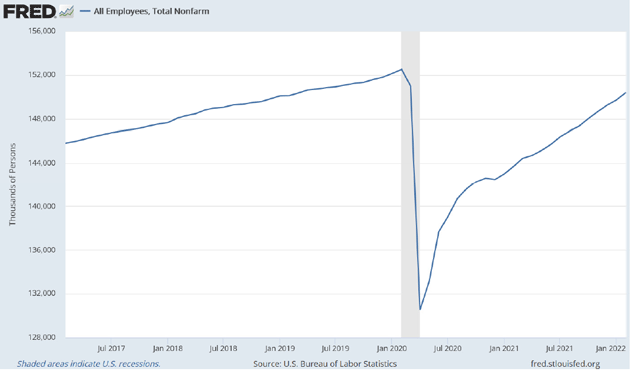

Let’s start with employment. Here is the latest US jobs picture.

Source: FRED

The total number of nonfarm jobs was growing steadily until the brief COVID-19 recession. It then fell hard and it still hasn’t fully recovered. It has been making good progress, though.

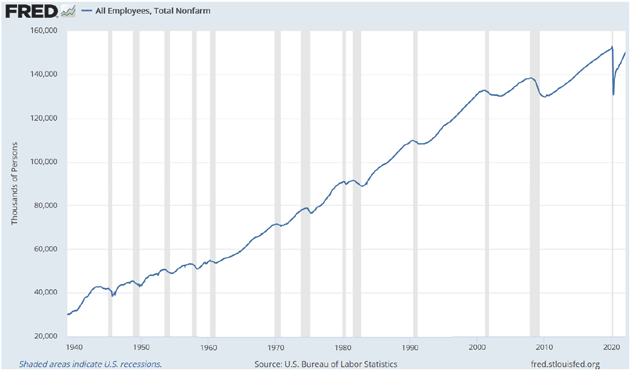

A longer-term look at this same data series shows that employment tends to peak just as recessions (the vertical gray bars) begin. But notice, since 1940 every pre-recession peak was higher than the last pre-recession peak. If the same doesn’t happen this time, we’ll have yet another reason to call this recession strange.

Source: FRED

Unfortunately, I think that scenario is possible. Today’s higher energy prices and war-related disruptions will start to bite soon. Businesses who are desperate to hire right now will see slower sales and stop adding staff. That’s the first step to reducing staff.

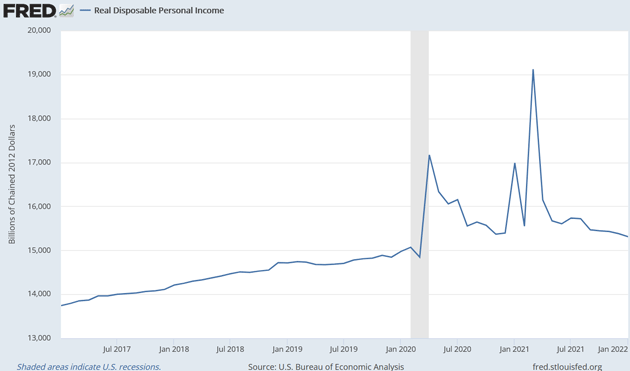

As for the second marker associated with recessions, declining real income, it’s already happening. But here again, it’s a strange picture. (Remember, this is inflation adjusted.)

Source: FRED

The chart shows income popping sharply higher in three peaks, which correspond to the three COVID-19 stimulus bills. If you extrapolate the pre-COVID-19 trend forward, today’s level is about where it should be. But it’s been declining for several months despite higher nominal wages, partly due to rising inflation.

But whatever the cause, people change their behavior when they perceive it is becoming steadily harder to make ends meet. Consumer sentiment surveys have been showing sharp drops, likely due to rising prices caused by supply chain issues and inflation.

Marker three, a manufacturing slowdown, is harder to measure with COVID-19 and supply chain problems in the mix. But it seems almost certain to decline as the war makes components and materials even harder to obtain than they are now.

Note, too, it doesn’t take much to disrupt production. The Financial Times had an interesting story last week about automotive wiring harnesses. Many European manufacturers source these from factories in Ukraine. It’s simply a little device to hold the various cables that snake through your car’s engine. They’re made to very precise specifications.

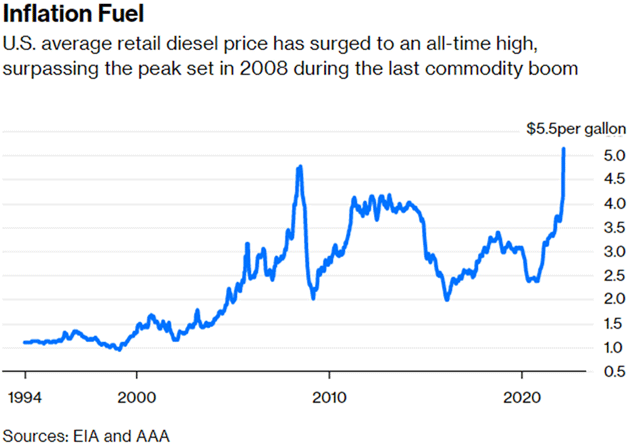

Unable to get them, BMW and Volkswagen have idled entire plants since the war started. That means lost sales, profits, and wages. Another example is increasingly scarce and expensive diesel fuel. In the US, diesel prices have almost doubled from the pre-COVID-19 level, with inventories at multiyear lows.

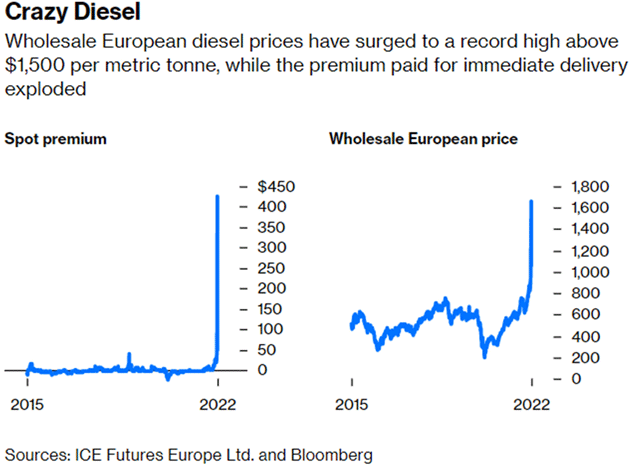

Source: Bloomberg

Europe’s diesel problem is even worse. Quoting from the Bloomberg article which sources the chart above:

“The loss of Russian supplies is particularly acute for northern Germany, which receives seaborne Russian cargos directly via Hamburg and other ports. In a reflection of the crisis, benchmark wholesale European diesel prices hit a new high last week. The premium for diesel for immediate delivery exploded—at one point, it was 100X more than usual—in a sign of extreme tightness.

“The situation is made worse because Europe doesn’t just import finished diesel from Russia, but also semi-processed oil that it further refines to make diesel. The lack of that feedstock, including vacuum gas-oil and straight run fuel-oil, is forcing some refiners to cut supplies. Both Shell Plc and OMV AG have started to restrict their wholesale supplies.

"OilX, a consultant, has told clients it sees ‘a real risk of physical shortages of diesel in Europe.’ Privately, oil traders and oil companies say the same. No one wants to raise the alarm, fearing a run on gas stations, but everyone is quite worried.

“If nothing changes, by early April, some European countries may need to restrict diesel sales to conserve supplies.”

We’ll see more such interruptions as the war’s direct impact, as well as the sanctions, reverberate through the economy. The microchip shortage was on the mend but may now get worse again. All this has snowball effects, one of which will be lower output.

The fourth and last inflation effect is lower consumer spending. This is also murky because the spending mix matters a great deal. When people have to spend more on food, fuel, and utilities, they have less to spend on other things. We saw with COVID-19 how these shifts can devastate certain sectors. A non-COVID-19 recession will look different but may not be much better.

Looking for Value

How does recession affect your investments? Obviously, it depends on how you are invested. But broadly speaking, recessions hurt. Stock and real estate prices fall, interest rates rise, and companies often cut or suspend dividends.

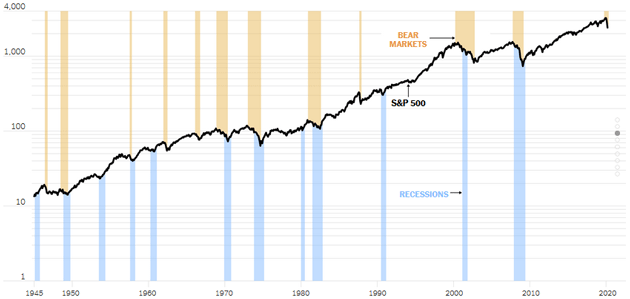

Here’s an interesting long-term look at the connection. The line is the S&P 500 since 1945 on a log scale. The blue bars are recessions and the brown bars are bear markets.

Source: The New York Times

You can see recessions and bear markets usually coincide, but not always. Nor are they always of the same duration. In theory, we could have a recession but stocks continue higher, or at least hold steady. I would not bet on it. And note carefully: What look like small blips on this very long-term chart are 40% to 50% declines, followed by years making up lost ground. This isn’t a case for buy-and-hold index fund investing.

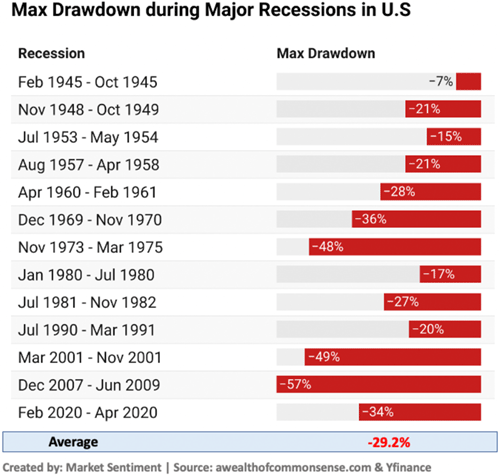

The table below shows the maximum drawdowns during major recessions since World War II. The 2001 and 2007 bears were particularly ugly.

Source: Market Sentiment

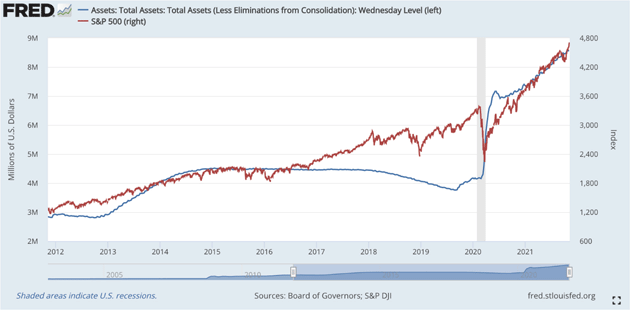

Massive QE helped the stock market recover in 2020‒21. Note below the extraordinarily high correlation between stock prices and quantitative easing, beginning on March 23, 2020.

Source: FRED

We can safely assume everybody on the FOMC is aware of this correlation. It’s why they only gave lip service to reducing the balance sheet. It will be interesting to see how rapidly (or not) the Fed’s assets actually fall. Like an addict coming off a drug-induced high, it could drag on stocks and make the bear market normally associated with recessions even worse.

The best way to “play” a recession, in my opinion, is to view it as a buying opportunity. That means hold cash and look for value. The tricky part is you never know where the bottom is, so today’s value could be an even bigger value next week. That’s frustrating but inevitable. And hopefully, you’re not buying to sell next week anyway.

Better to get a good price and sell in the next bull market when it is absurdly overpriced. And make no mistake, I fully believe there will be another bull market, it may just not have the rocket fuel of quantitative easing for several years as the Fed continues to fight inflation.

Lengthy Transition

Everything I said to this point is the “conventional” recession scenario. But we already know this one isn’t conventional. I don’t expect it to look like 2000 or 2008 at all. A better analogue is the 1970's stagflation era.

That was an entirely different world, and certainly different kinds of markets. There were no ETFs back then. Mutual funds were a new idea and the 401(k) hadn’t been invented yet. Online trading was science fiction. So, it’s hard to visualize how that kind of recession will combine with today’s kind of markets. We haven’t seen anything like it.

I keep saying this, but it bears repeating: Most recessions are deflationary events. Consumer prices decline as growth weakens. That’s one of the qualities that makes them bearable, though not pleasant. Your income falls but so do your living costs. Stagflation isn’t like that. Your income falls while your living costs rise—in this case, due mainly to higher energy costs.

We will see this directly in fuel and utility bills, and indirectly in many other expenses. In some respects it will be like a value-added tax, tacked on to prices at every level of production. But this is hardly tax reform. All the usual taxes will continue, at current rates if not higher. Then we’ll have the new energy “tax” on top of them. It won’t matter what Congress does or how you vote. The tax will be there and you’ll have to pay it.

Larry Summers Weighs In

Larry Summers wrote a particularly somber Washington Post op-ed this week, gruesomely titled: “The Fed is charting a course to stagflation and recession.” Only a few weeks ago he was talking about how difficult the choices facing Jerome Powell would be. Now he feels the choices they’re making will have very ugly consequences. I’m going to quote a few paragraphs, but the entire piece is really worth reading.

“Anything is possible, and wishful thinking can sometimes prove self-fulfilling. But I believe the Fed has not internalized the magnitude of its errors over the past year, is operating with an inappropriate and dangerous framework, and needs to take far stronger action to support price stability than appears likely. The Fed’s current policy trajectory is likely to lead to stagflation, with average unemployment and inflation both averaging over 5 percent over the next few years—and ultimately to a major recession.

“Powell has emphasized his admiration for Paul Volcker recently. Current inflationary conditions are not as bad as those Volcker inherited as Fed chair in 1979, but they are the worst since then. To prevent inflation from metastasizing, Powell and his colleagues need to be absolutely clear on two propositions that Volcker took as axiomatic.

“First, price stability is essential for sustained maximum employment, while overheating the economy leads to stagflation and higher levels of average unemployment through time.

“Second, there can be no reliable progress against inflation without substantial increases in real interest rates, which mean temporary increases in unemployment. Real short-term interest rates are currently lower than at any point in decades. They likely will have to reach levels of at least 2 or 3 percent for inflation to be brought under control. With inflation running above 3 percent, this means rates of 5 percent or more—something markets currently regard as almost unimaginable.”

Think about that for a moment. Summers knows full well what such a policy would mean to the economy. But he (and I agree) feels letting inflation get out of hand is an even worse option.

The current go-slow, 25 basis points per meeting plan may have the desired effect of not spooking the financial markets, but it will also let inflation expectations increase and lead to wage and price spirals. I can’t emphasize enough how dangerous this particular environment is.

In fairness, numerous economists and analysts believe Powell has everything under control, and will taper the balance sheet more than expected. I hope they are right.

My belief is the Federal Reserve made its major monetary mistake well over a year ago. Arguing in August 2020 that letting inflation run hot wouldn’t be that bad, that inflation would be transitory, simply brings up the ghost of Arthur Burns. Combine inflation with supply chain issues, plus war-related energy and food shortages, and we have a very volatile mixture.

Eventually, inflation will be brought under control and we will be back to a disinflationary/deflationary environment under the weight of a heavy debt load. But the current path the Fed is on could mean “eventually” is more than a few years.

The saying in uncertain times is “hope for the best, plan for the worst.” I certainly hope the war ends quickly through some series of events that bring Russia back into the global economy quickly. I don’t anticipate it. I think we are transitioning to a new era and the transition could take some time—not months but years. Here in the US we aren’t feeling much pain yet. We will.

We are entering an extended period of sharply higher energy and food prices, which will raise the cost of everything else. Add to it the shortages we will see in the commodities that enable all our electronic devices and infrastructure, and higher financing costs as the Fed raises rates and may well overshoot.

It’s going to be difficult. But it will also bring opportunities, which I’m excited to explore. I do believe in the American entrepreneur and in the future of marvelous technology.

Disclaimer:The Mauldin Economics website, Yield Shark, Thoughts from the Frontline, Patrick Cox’s Tech Digest, Outside the Box, Over My Shoulder, World Money Analyst, Street Freak, Just One ...

more