Price For Clarity

The market hates ambiguity. That’s what we’re told, and on any short-term basis, we can see the market vote accordingly. In a world where investing has morphed towards algorithmic trading systems influencing daily volatility, many have come to accept this as a reasonable truth and participate by selling when things lose clarity or piling in when visibility is perceived.

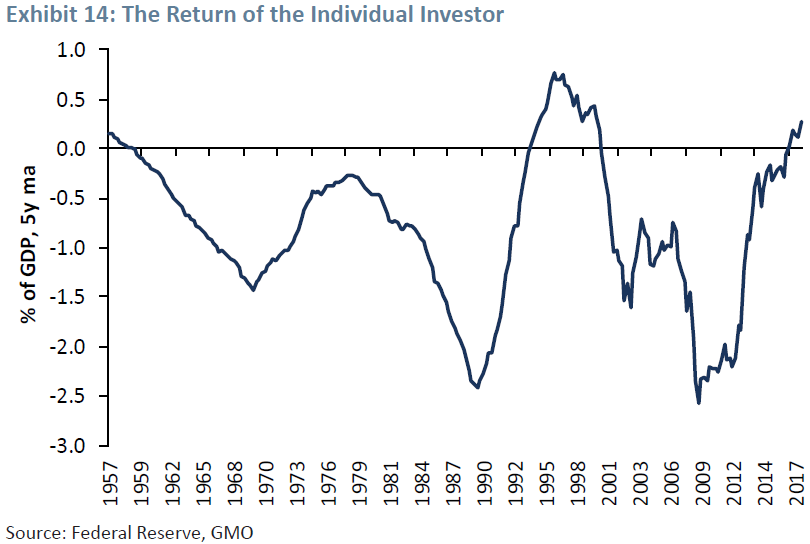

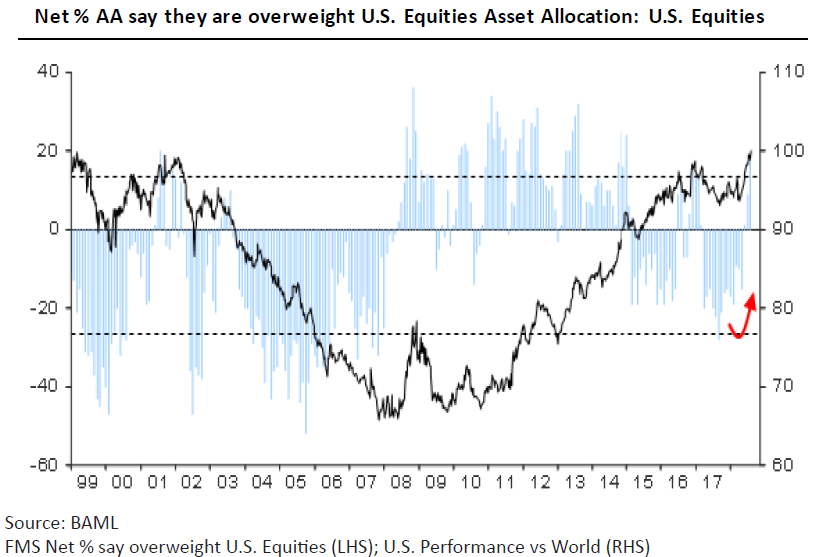

This is a very easy way to invest. It is most comfortable on your nerves, by a longshot. Not only that, but in recent years it has worked well. After all, pretty much anytime that you may have bought Amazon (AMZN) or Netflix (NFLX) over the past decade (up until late summer 2018), you’ve paid a lot more for increased perceived visibility, but were awarded with even higher stock prices later. The price paid for supposed clarity stopped mattering long ago, exacerbated by a prolonged period of low interest rates. This seemingly safe and complacent market has also wooed individual investors and asset allocators (“AA” in the below right chart) back to the party successfully.

Such one-direction markets don’t require a lot of courage. Even the word may feel a little new in today’s investing conversation. A recent interview of well-known hedge fund manager Stanley Druckenmiller by Bloomberg’s Erik Schatzker asked what necessary qualities and characteristics might be required for success of a money manager coming into the business today. We love Mr. Druckenmiller’s response, and think it is timeless:

“I think the number one thing you need is […] courage, and when I say courage, you need courage to bet big and bet concentrated, but also the courage to fight your own emotions. I’ve never made a buy at a low that I didn’t feel just terrible and scared to death making it. It’s easy to sell at the bottom. […] When things are going up it’s easy to buy them, when they’re going down it’s hard to buy them.”

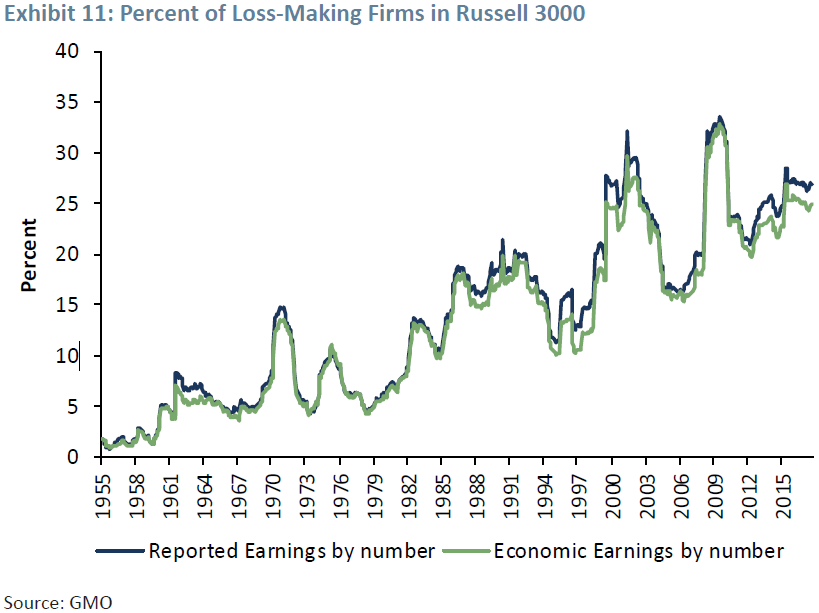

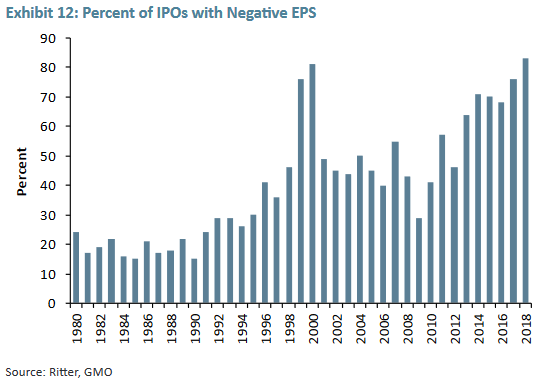

Of course, courage – like beauty – may lie in the perception of the world around you. In our view, it is far riskier owning companies that lose money, than those that gush profits or cash flow (part of our criteria for stock selection). This may sound incredibly simplistic, if not obvious, but when money has become so cheap for so long (interest rates), investors have been quite willing to sponsor companies who bleed red:

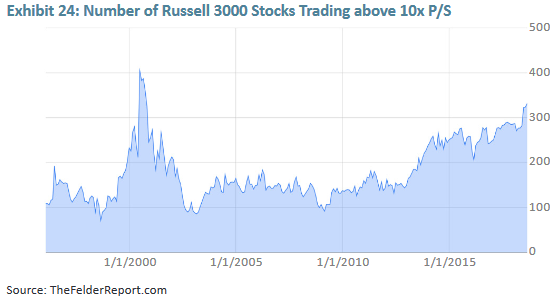

Investors have also been paying nosebleed prices for perceived clarity. Most readers are likely well informed of our chart showing the substantial bifurcation between the richest vs. the cheapest quintile of stocks within the S&P 500. You have to look back to the late 1990’s to find as wide a differential as you will find today between the 100 richest and 100 cheapest security buckets. We came across the below chart showing the number of stocks within the Russell 3000 Index that trade at levels above 10x price-to-sales, which shows a similar picture of unabated enthusiasm for “growth” stocks:

I remember in 1999 when the popularization of using price-to-sales became a preferred valuation concept. It was either that, or “price-to-eyeballs,” referring to how many impressions an internet company would capture over a certain period. Fast forward a couple decades, and it seems top-line revenue growth is again commanding investor attention. These are ideas that come to the front of the line when profits or cash flow are scarce. Back in the ‘90s we talked about it as the “new economy” and today we justify it because we imagine the future profits that may take place if or when the capital-expenditure spigots are turned off by these high-growth companies. We won’t hold our breath on that one.

This kind of imagining is not courage. It is the kind of stuff that happens when money has been persistently cheap for a prolonged period. It is the kind of thing that takes place when the venture capital deal-size has mushroomed ten-fold over the past decade. These pockets where valuation levels are ignored for “clarity” defined by revenue growth makes the grading of De Beers’ diamond stones look like kids play. Malinvestment due to ignoring valuation and throwing caution to the wind on price never ends well. It is also perfectly avoidable. To do so, you must have courage. You must avoid groupthink. You must be contrarian!

Those who have forgotten the adage “don’t confuse brains with a bull market” were reminded of it in late 2018. The market is sorting this out and we believe it will ultimately lean away from companies trading at price levels that offer investors no margin of safety. This is likely to result in an investing landscape that awards high-quality companies that generate the things you would look for if you owned a company privately: profits and cash flow for its owners. We think these kinds of opportunities exist among homebuilders, select consumer-oriented companies, financials, health-care and media companies.

Source for all charts shown: GMO White Paper, The Late Cycle Lament: The Dual Economy, Minsky Moments, and Other Concerns, December 2018.

Disclosure: This article contains information and opinions based on data obtained from reliable sources, which is current as of the publication date, and does not constitute a recommendation ...

more