Perpetual Boom

Let’s talk about the business cycle for a second.

Like the fact that we don't have one anymore.

In the old days, we used to get expansions and recessions. The authorities generally didn’t mess around too much with the business cycle.

If they did, they did it in a countercyclical way—hiking interest rates when the economy got hot, and taking the punchbowl away.

Nowadays, the authorities act in a procyclical way, easing monetary policy even more in the middle of a roaring expansion. This has left us without a business cycle.

- We are now constantly in a state of a perpetual boom, punctuated by the occasional sharp crisis where we all have a near-death experience.

That is a function of monetary policy, yes. But it is also a function of going off the gold standard in 1971. Most of the economic distortions that we experience today can be traced to that cataclysmic event.

One could make the argument that if we hadn’t experienced a global pandemic, then the economy would have never gone into recession. Twelve consecutive years of economic expansion, and possibly more.

That falls under the definition of perpetual boom, punctuated by the occasional crisis, which we had about a year ago.

- The perpetual boom model is perhaps the most important thing to understand about today’s markets.

That's because it has implications for the underlying distribution of asset prices. It also has implications for volatility and options trading. It even has implications for how you conduct your daily life.

Let’s talk about this.

Stocks

Stocks basically go up all the time, and when they don’t, they crash. What kind of distribution is this?

It’s not a normal distribution, that’s for sure. It’s a bit skewed to the right, with a massive left tail.

Now, if I had the mathematical tools, I could graph this distribution, and then look at option prices, and graph an implied distribution based on that, and compare them.

I think what you’d find is that the tails are massively underpriced. And we know this to be true because performance of tail-risk funds has been pretty good.

From a risk-management standpoint, it puts you in a little bit of a pickle, because you’re supposed to stay fully invested—and then experience a breathtaking drawdown every so often.

- This puts people in a position where they have to hedge—and very few individual investors are sophisticated enough to hedge.

Plus, hedges are expensive, and few investors have the fortitude to buy money-losing puts every month.

Diversification across asset classes becomes even more important. Under the perpetual boom/crisis model, a portfolio of 100% equities becomes almost impossible to hold as a long-term investor.

In a perpetual boom world, where we have frequent crises, there is a good chance that you are going to lose your job.

In a normal economic cycle, there are always layoffs. But the downturns are a bit more gentle, and businesses can often cut costs in other ways so as to minimize layoffs.

But when it looks like the world is ending, like what happened last year, businesses simply disappear, and millions of jobs are lost.

You might say that the pandemic is a bad example—it was a big, exogenous event, after all.

- In a normal economy without as much leverage in the system, that wouldn’t turn into an end-of-the-world event, where people are actually contemplating shutting down the stock market.

That’s how bad things got last year because we went into the crisis with an insane amount of leverage. There’s even more leverage today.

The tail-risk guys tend to be libertarian macro doom guys. They often go around predicting financial collapse and a return to the gold standard. They’ve been singing this tune for 20 years or more, but we’re getting closer to that day (though it still might be years away).

I am not too much into financial philosophy, but keep in mind that a flexible monetary standard is a pretty short experiment—only about 50 years. And except for a few hiccups, we’ve managed to keep the global economy in perpetual boom mode.

- But what if we’ve merely lengthened the business cycle, not eliminated it?

What if, following a 50-year boom, we have a 50-year bust? What would that look like?

If that happens, there will obviously be bigger things to worry about, but an 80% stocks/20% bonds portfolio is not going to work in that scenario.

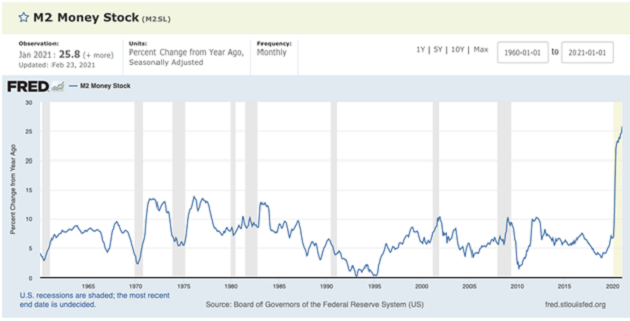

We have a lot of debt and money printing. More than 25% of all money in existence was printed in the last year.

Source: St. Louis Fed

When I tell people that sorry statistic, they typically look at me and ask, is that sustainable? And I just shrug. Party on.

But we’re setting ourselves up for a much, much bigger crisis down the road. The real problem with big crises is that they change politics in fundamentally malignant ways.

There’s an old article from me on ZeroHedge from five or six years ago where I said that the next recession would be the end of capitalism as we know it. That wasn’t that far off.

Can’t wait to see what the next one will bring.

Disclaimer: The Mauldin Economics website, Yield Shark, Thoughts from the Frontline, Patrick Cox’s Tech Digest, Outside the Box, Over My Shoulder, World Money Analyst, Street Freak, Just One ...

more