Do You Need An Annuity For Retirement?

The even-more-ridiculously-acronymed-than-usual SECURE Act (that's Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement) has made it through the House of Representatives, and could make it through the Senate soon (though a couple of senators are holding it up at the moment). The act proposes a number of things, but one big one is that it will likely allow annuities to be offered in retirement plans--such as 401(k)s--more easily.

Plan administrators have mostly been shy to offer annuities for fear of being held accountable should the annuity's issuing company fail. The new legislation relaxes some of the fiduciary responsibilities, making it potentially more palatable for administrators.

Whether the bill makes it through in any form, we thought its existence would be a good excuse for taking a closer look at annuities, and talking about whether they're needed in a retirement plan or not.

Better Late Than Never, or Better Never Than Late?

Why now, you ask? Others might ask, why not before now? That's because by some measures, defined contribution plans (such as 401(k) plans) have not lived up to expectations.

Some of this is investors' faults, but some is not. If you're not saving enough--and of course we know most people are not--that's largely on you. But there is a big piece of 401(k) plans that is largely out of participants' control. If the investment choices are bad (specifically, if the fees are high), there's normally nothing you can do about it. And if you don't know much about investing, you may feel overwhelmed or bewildered by the choices. Nobody expects you to fix your car engine (unless you're a trained mechanic); why do we expect you should be able to plan your retirement?

Enter annuities. The best of them are easy to understand, even by financial novices: Give us your money, and we'll give you this much money per month until you die. Sounds simple.

But simpler isn't always better (though it usually is in investing). For one, annuities have fees as well, and they can be stupidly high. As with mutual funds, you may not know what constitutes a high fee versus a fair fee for the services you're receiving. Also, if you change your mind and want the money back, you'll be paying a surrender charge.

Another big negative that always comes up with insurance-related products (which this basically is) is the risk that the issuing company, which seemed so healthy when it sold you the annuity, goes out of business 30 (or however many) years out, just when you are scheduled to start taking payments.

That's a real risk, but probably not as big as it seems. For one, such failures don't happen very often. But beyond that, you have an insurance policy for your insurance policy. That is, at the state level, there's something called a Life and Health Guaranty Association that will usually cover up to $250,000 of the present value of your annuity benefits. In some cases, the limit on the high end is $500,000. You can think of it as a sort of state-run Securities Investor Protection Corporation (SIPC), which is the federally mandated non-profit organization that covers you--to a point--if a broker or investment firm goes under. If your state would cover you up to your annuity's value, great: you needn't worry about the going-out-of-business risk. But you should probably know your state's rules and limits before buying.

Your Choices

Annuities aren't all alike, so let's start with some definitions.

Variable annuities are ... you know, let's skip variable annuities. And you should skip them too. They're too complicated, too expensive, and mainly a solution in search of a problem. Don't mess with variable annuities.

Your other two main options are fixed immediate annuities and deferred income annuities.

Fixed immediate annuities are basically what they sound like. You usually make a single premium payment, and then the income starts monthly for the rest of your life. It may also pay out for the rest of your spouse's life too, depending on its terms.

If you want it simple, it doesn't get much simpler. The certainty of knowing what you'll be receiving each month should provide peace of mind.

Deferred income annuities are very similar, but don't start paying out for a while (that's the deferred part). Because the issuer has time to invest your money before starting to pay you, your premium should be relatively small.

If an investor wants a guaranteed payout for a surviving spouse, or even if he or she wants to just invest a portion of their wealth into an annuity, we'd grudgingly say "OK." Not everyone has the same risk tolerance, and it's hard to put a price on sleeping well.

Our view, though, has long been that most people can handle income generation in retirement themselves, with the help of dividend-paying stocks such as Johnson & Johnson (JNJ), Exxon (XOM), and Procter & Gamble (PG).

Know What You're Paying For

Investing costs money. That is, you're putting your hard-earned dollars into something that should make you more of those dollars, but you're also paying for the ability to do so in one form or another. It could be trading commissions, mutual fund expenses, fees for managing a certain quantity of assets--there are lots of ways you pay.

So a big part of a successful investment plan is to know what your investments cost. Fees and expenses can have a surprisingly large effect on total returns over time. That's not just for annuities--that's for everything.

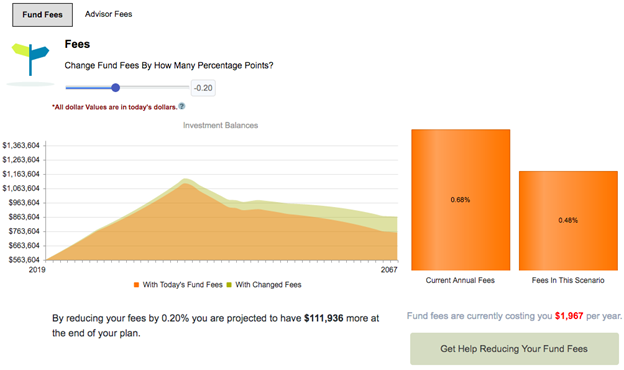

It's easier to understand the effects when they're presented graphically. In this example, which we ran through WealthTrace, dropping fees by just 20 basis points (that's 0.20%) leads to an extra $112,000 at the end of the retirement plan.

The Facts Don't Change

We don't know if the legislation making it easier to purchase an annuity via a retirement account will get through, or what form it will take if it does. Regardless, what's needed to make a retirement plan successful remains the same. Investing is risk taking; people's comfort with taking risks varies. If an annuity ends up in a risk-averse investor's arsenal--using money they might have otherwise just foolishly stashed away in a bank account--that's OK. But if you're relatively early in your investing years, and quite a ways from retirement, it's probably going to be better to take bigger risks--and get higher returns--with the bulk of those assets.