Palladium – All That Glitters Is Not Gold

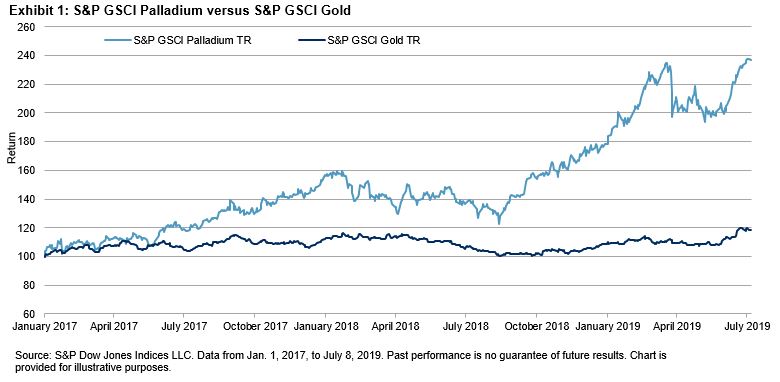

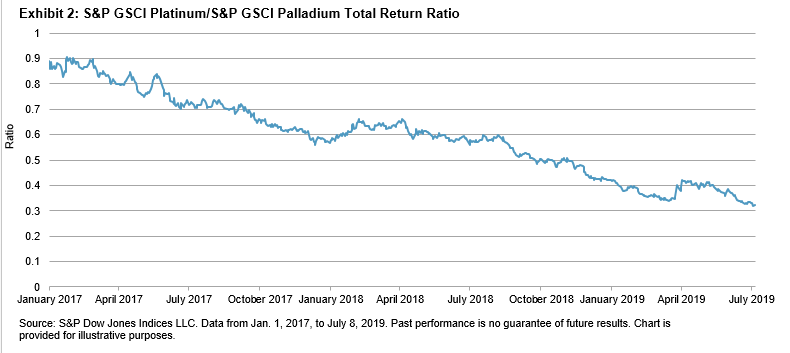

Much has been made during recent months of the renewed interest investors have shown in gold on the back of growing financial market turbulence, a plethora of geopolitical flashpoints, and a string of economic releases that have fallen short of expectations. But gold has not been the shiniest precious metal this year; back in January, palladium became the most expensive precious metal for the first time since 2002, and by July 8, 2019, it had reached USD 1,542 per troy ounce, a premium of almost USD 150 to gold. When compared to its sister metal, platinum, the performance of palladium has also been impressive, with the platinum/palladium ratio more than halving since the beginning of 2017.

Drivers of performance in the palladium market were a mix of broader, macro demand trends and commodity-specific supply constraints.

Approximately 80% of palladium demand comes from the automotive industry. Its other uses include electronics, dentistry, and jewelry. As regulations on emissions have tightened, demand for palladium to be used in the catalytic converters of gasoline-powered vehicles has risen. Gasoline vehicles have also become more popular in the wake of a number well-publicized diesel emissions scandals (diesel-powered cars use platinum in their catalytic converters).

Palladium’s outperformance relative to platinum has rightly raised the question of substitution. While it may be theoretically possible for carmakers to switch from palladium to platinum, further technical advances and a reasonable lead-time are likely required. It is also worth noting that even with a rally in price, the cost contribution of palladium in car manufacturing is low and may not warrant significant research and development resources, especially when the future of passenger travel may not revolve around the combustion engine.

Electric vehicles do not burn fuel and hence do not require catalytic converters; however, it is not clear how quickly the mass adoption of electric vehicle technology will occur and hence how long it will take for palladium’s largest end market to shrink and eventually disappear.

Palladium is a by-product of platinum and nickel mining and is primarily mined in South Africa and Russia, and both countries face a myriad of investment and production challenges. Palladium prices spiked in March 2019 when Russia’s Ministry of Industry and Trade announced it was considering a temporary ban on the export of precious metal scrap and tailings, while in South Africa, the world’s largest platinum miners are about to embark on a series of wage negotiations with unions, which in the past have led to lengthy mine strikes.

As a by-product, it is not just the prospects of the palladium price that are taken into consideration when a miner makes a short-term capital expenditure or longer-term investment decision.

One area where supply is expected to increase over the coming years is the secondary scrap market. As more and more end-of-life vehicles contain a significant amount of palladium in their autocatalysts, the level and sophistication of recycling will likely increase.

The S&P GSCI Palladium is up 32.8% YTD, making it one of the best-performing individual commodities during the first half of 2019. Its performance in the second half of the year and beyond will depend equally on the ongoing push for lower car emissions and the supply challenges of not being the primary product mined.

Copyright © 2018 S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, a division of S&P Global. All rights reserved. This material is reproduced with the prior written consent of S&P DJI. For more information ...

more