China's Employed Population Shrinks For The First Time Ever

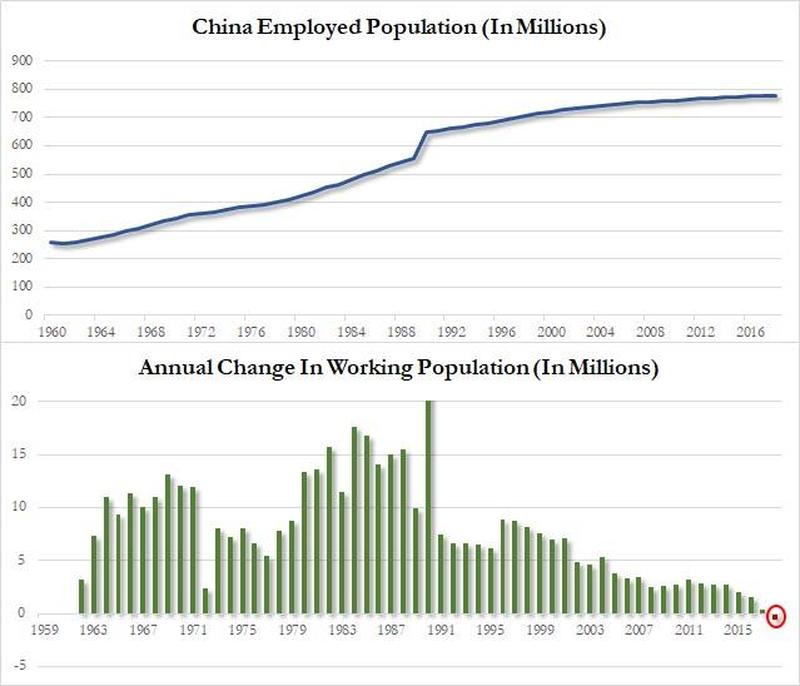

China's imminent, and historic conversion from a current account surplus to deficit nation is not the only "tectonic shift" taking place in the world's most populous nation. According to the latest census data from its National Bureau of Services, China's employed population has shrunk for the first time ever on record, and at the end of 2018, the number of people employed fell to 776 million, a drop of 540,000 from 2017.

Meanwhile, in yet another sign that China’s population is aging rapidly, the broader working-age population, or people between the ages of 16 and 59, also shrank for the seventh consecutive year, down a total of 2.8% from 2011 to 2018 according to Caixing. Last year’s China's total working-age population stood at 897 million, down 5 million from 902 million in 2017, according to the NBS.

Li Xiru, director of the Population and Employment Department at NBS, warned last month that the employed population would further drop in the coming years.

While China is already beset with a myriad of economic and asset price bubbles, most notably a massive corporate debt load and a still gargantuan shadow banking system both of which it has to balance against an unprecedented housing bubble to avoid a collapse in the financial system sparking a "working class insurrection", the country’s shrinking work force creates even more headaches for officials as it pushes up labor costs, sparking inflationary pressures and placing more strains on an economy already struggling against external headwinds.

As China Daily reported recently, the shortage of workforce means labor cost will continue to increase and industrial transfer and technology will substitute workers. And since university graduates - who expect far higher wages - account for nearly half of the labor force entering the market, the market is unable to provide traditional industries with the required number of workforce and the past high-input economic development mode is unsustainable.

The futures is even bleaker: the working-age population is expected to see a sharp drop from 830 million in 2030 to 700 million in 2050 at a declining speed of 7.6 million every year, said Li Zhong, a spokesman for the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, in July. Meanwhile, with decreasing supply of labor force, the salary of all industries grew at a rate of 11.3 percent in 2011, 10.5 percent in 2012, and 9.7 percent in 2013, said Zeng, adding that as a result many foreign enterprises left China and shifted to Southeast China due to rising labor cost.

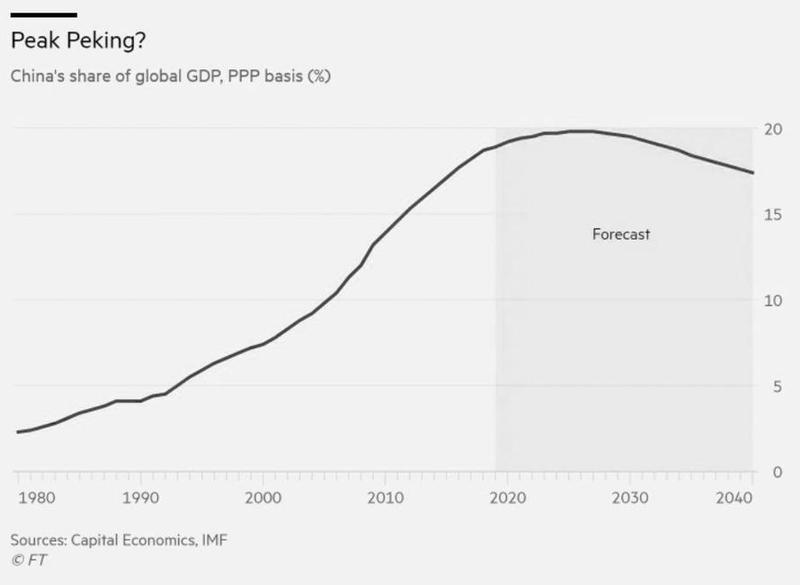

Adding to the warnings, back in 2015, the World bank cautioned that China’s working age population will fall more than 10% by 2040 in spite of a recent relaxation of its one child policy, heightening the risk of the world’s most populous country “getting old before getting rich”.

A further decline of 10% would equate to a net loss of 90 million Chinese workers, a number greater than the population of Germany, and is consistent with demographic pressures across East Asia. The working populations of South Korea, Thailand and Japan are also expected to fall by 10 per cent or more over the next 25 years.

“East Asia has undergone the most dramatic demographic transition we have ever seen,” said Axel van Trotsenburg, World Bank regional vice-president. “All developing countries in the region risk getting old before getting rich.”

As of 2010, almost 40% of all people on the planet aged 65 or older — some 211 million individuals — lived in East Asia, and the World Bank estimates that a least a dozen East Asian countries will see the percentage of their populations aged 65 or higher double to 14 per cent in a quarter century or less. In France and the US, the same transformation took 115 and 69 years respectively

“As [countries] get richer, fertility falls,” said Philip O’Keefe, lead author of the World Bank report. “Given China’s current fertility [rates], you may get a temporary uptick in people who wanted to have a second child having one, but we don’t see a big long-term impact there.”

O’Keefe cited surveys showing that only a quarter of Chinese people eligible to have a second child would in fact do so, however according to recent data, despite China's relaxation of the infamous "one-child policy", local birth rates have remained stagnant and in fact, in 2018 China's birth rate dropped to a new record low.

Commenting on China's demographic collapse, Wang Feng, a sociology professor at the University of California, Irving, said: "Decades of social and economic transformations have prepared an entirely new generation in China, for whom marriage and childbearing no longer have the importance they once did for their parents' generation."

The World Bank urged East Asian governments to embrace immigration as one tactic to counter falling population pressures, noting that more than 20% of Australians and New Zealanders — and 40% of Singaporeans — were immigrants, although Europeans may offer some counterpoints against opening up one territory to a flood of foreigners...

“Demography is a powerful force in development but it is not destiny,” Mr O’Keefe said. “Through their policy choices, governments can help societies adapt to rapid ageing.”

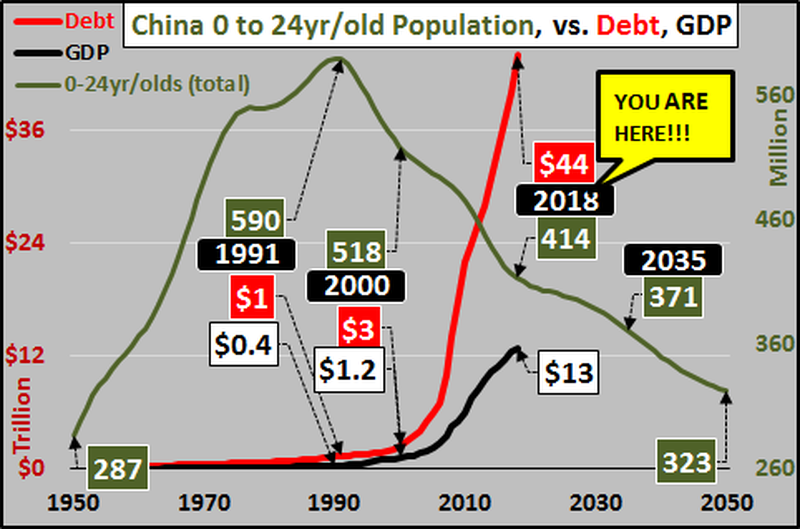

Of course, besides demographics, China's transformation into the next Japan has major, and potentially dire, consequences for the local economy. As we reported back in October via Econimica, the 0-to-24 year old Chinese population swelled by over 300 million from 1950 to it's ultimate peak in 1991. Since that peak, the total population of young in China has fallen by 176 million, or a 30% decline in the number of children across China.Moving forward, the UN has expressed hopes the formal elimination of the one child policy would simply slow the rate of decline in the population...but by no means will China's fast declining childbearing population (those aged 15-44) nor disproportionately young male population potentially be offset by a slightly less negative birth rate. Contrast that with the quantity of debt being forcibly injected into a nation that faces a massive imminent population decline.

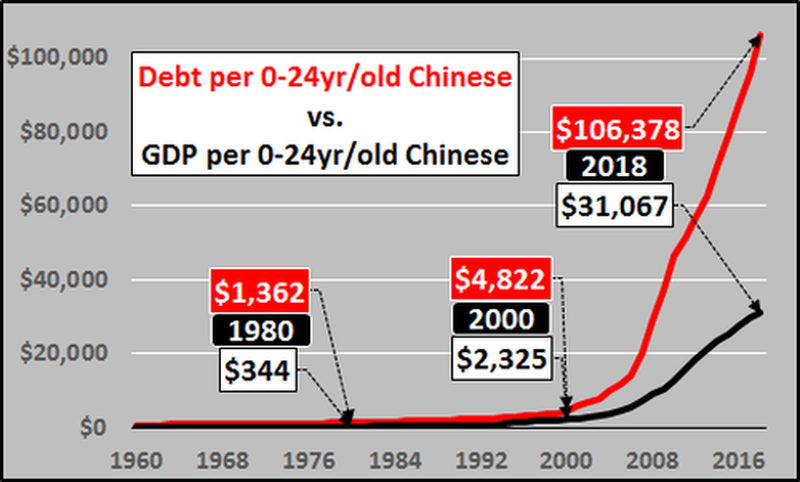

To put that debt into perspective, the chart below shows that total debt and annual GDP each divided by the 0 to 24 year old Chinese population.As of 2018, every child and young adult in China under the age of 25 is presently responsible for over $100 thousand dollars in debt while the annual economic activity (GDP) created by all this debt continues to lag ever faster.

And the coming decade only worsens as the young population continues its unabated fall and debt creation (absent concomitant economic growth) continues soaring... building more capacity all for a population that is set to collapse.

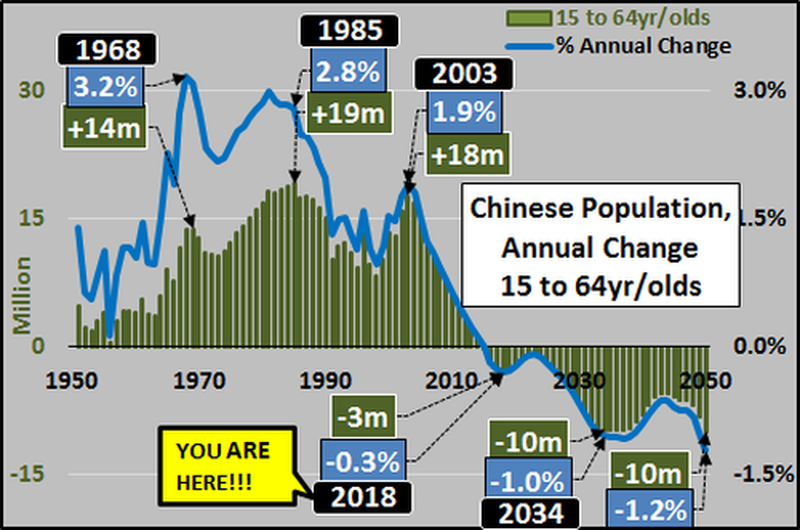

China's predicament and reaction to it are not particularly unique...but given China's size, the ultimate global impact of China's slow motion train wreck will be unprecedented... particularly as their 15 to 64 year old population is now in indefinite decline.Chart below shows annual change in Chinese 15 to 64 year old population, in both millions (green columns) and percentage (blue line).

Simply said, without a dramatic rebound in China's birth rate, massive overcapacity (thanks to over a decade of government mandated malinvestment) versus an ever swifter declining base of consumption does not add up to a burgeoning middle class or a happy ending.

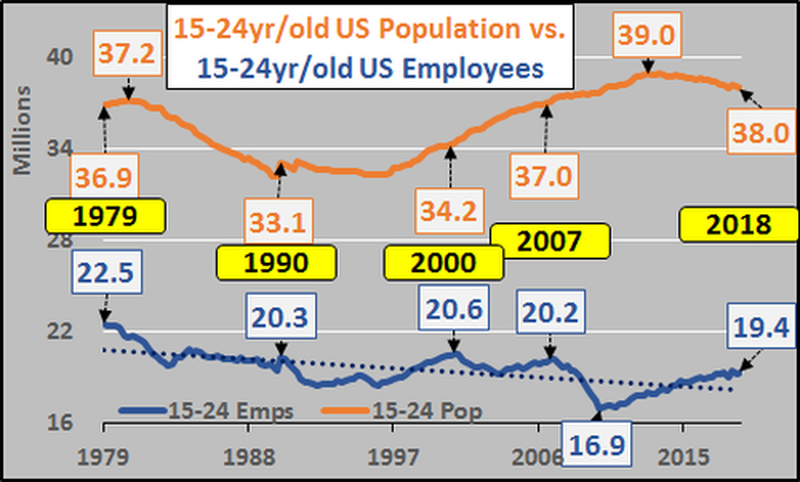

Of course, it's not just China: for context, here is a chart showing US federal debt per capita of the 0 to 24 year old US population...

... confirming that the next generation, whether in China or the US, is set for a painful collision course with debt bubble dynamics