Is It Monetary Or Credit Policy?

On September 13, at the FOMC meeting, the Fed announced another round of quantitative easing. Quantitative easing is the process where the FOMC purchases bonds on the open market in an attempt to stimulate the economy. Below are excerpts from the announcement:

On September 13, 2012, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) directed the Open Market Trading Desk (the Desk) at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York to begin purchasing additional agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS) at a pace of $40 billion per month. The FOMC also directed the Desk to continue through the end of the year its program to extend the average maturity of its holdings of Treasury securities as announced in June and to maintain its existing policy of reinvesting principal payments from the Federal Reserve's holdings of agency debt and agency MBS in agency MBS.

The FOMC noted that these actions, which together will increase the Committee's holdings of longer-term securities by about $85 billion each month through the end of the year, should put downward pressure on longer-term interest rates, support mortgage markets, and help to make broader financial conditions more accommodative.

To support continued progress toward maximum employment and price stability, the Committee expects that a highly accommodative stance of monetary policy will remain appropriate for a considerable time after the economic recovery strengthens. In particular, the Committee also decided today to keep the target range for the federal funds rate at 0 to 1/4 percent and currently anticipates that exceptionally low levels for the federal funds rate are likely to be warranted at least through mid-2015.

The big announcement was the upcoming purchases of MBS at a rate of $40 billion per month in addition to operation twist, where they will continue to sell the short end of the yield curve for longer maturity Treasury bonds. In total, they expect to increase exposure to long-term securities by $85 billion per month. Also, they anticipate keeping the fed funds near zero through at least 2015.

So, is it monetary policy or credit policy?

An interesting discussion was started by the St. Louis Fed's Daniel Thorton in this paper. Considering the extent of credit's role in the American economy, it could make sense to cater policies to interest rates and not necessarily money itself - there is a distinction. Credit, although readily substituted in this day and age, is not in itself money, even if the credit is almost exclusively based against money. The money underlying credit is still final medium of settlement; credit transactions add a time component to the exchange. So we need to ask ourselves two questions: (1) What are the policy needs for the money itself? And (2) What are the policy needs of the credit priced in the currency?

To me, the announcement seems more aimed toward the credit side of things, so let's start there.

The promise to purchase $40 billion of agency MBS monthly will undoubtedly lower rates on mortgage backed securities. The originators of the mortgages, the banks, are helped as the yield spreads between the mortgages they underwrite and the securities they sell should be improved. So they can either offer lower rates on the mortgage, which is good for consumers and could stimulate lending demand, or they can improve their own balances sheets with bigger spreads, or a combination of both.

Despite the continued pledge for FOMC participation in long bonds, these securities were hit hard on the tail of this announcement. In the two trading days following the move, money exited low-yielding treasuries. Even with the Fed still willing to buy into the market, the yields offered on these securities need to compensate other potential investors for inflation expectations over the duration of the bond. When the Fed promises to be as accommodative/dilutive as possible, investors fear a negative real return on long bonds because of inflation. So conceivably, yields could rise despite the buying pressure from the Fed.

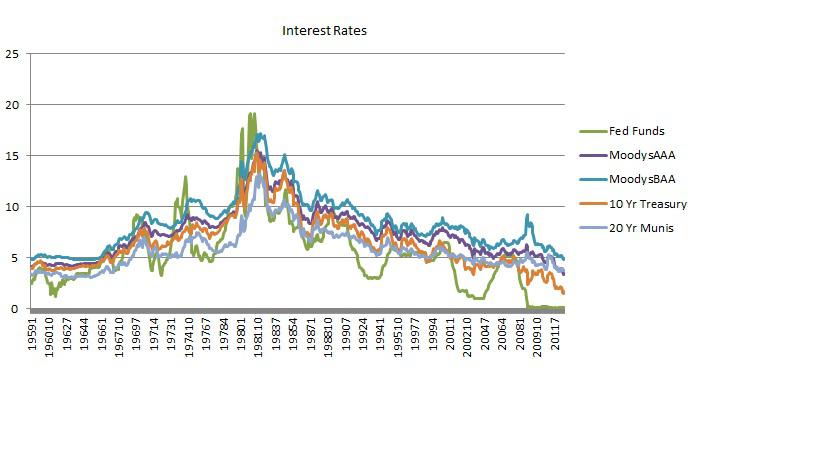

If treasury yields do continue to rise, corporate borrowers could be affected negatively with rising yields because their credit is still denominated in USD. As the issuer of currency, the Treasury bonds of the same duration will need to be lower yield than an entity with additional stand-alone insolvency risk. So for corporations with a lot of debt, borrowing costs may become more of a burden. So despite the move being generally liquidity-promoting, I think the impacts on the credit markets are far more positive for banks, and much less so for other corporate borrowers. Especially if and when yields rise across the board. Shown below are time series of select bond yields.

On the monetary side of things, the move seems pretty unnecessary. The most commonly used metric for money supply base is M2. M2 by definition is:

M2 includes a broader set of financial assets held principally by households. M2 consists of M1 plus: (1) savings deposits (which include money market deposit accounts, or MMDAs); (2) small-denomination time deposits (time deposits in amounts of less than $100,000); and (3) balances in retail money market mutual funds (MMMFs). Seasonally adjusted M2 is computed by summing savings deposits, small-denomination time deposits, and retail MMMFs, each seasonally adjusted separately, and adding this result to seasonally adjusted M1.

And as follows, the definition for M1 is:

M1 includes funds that are readily accessible for spending. M1 consists of: (1) currency outside the U.S. Treasury, Federal Reserve Banks, and the vaults of depository institutions; (2) traveler's checks of nonbank issuers; (3) demand deposits; and (4) other checkable deposits (OCDs), which consist primarily of negotiable order of withdrawal (NYSE:NOW) accounts at depository institutions and credit union share draft accounts. Seasonally adjusted M1 is calculated by summing currency, traveler's checks, demand deposits, and OCDs, each seasonally adjusted separately.

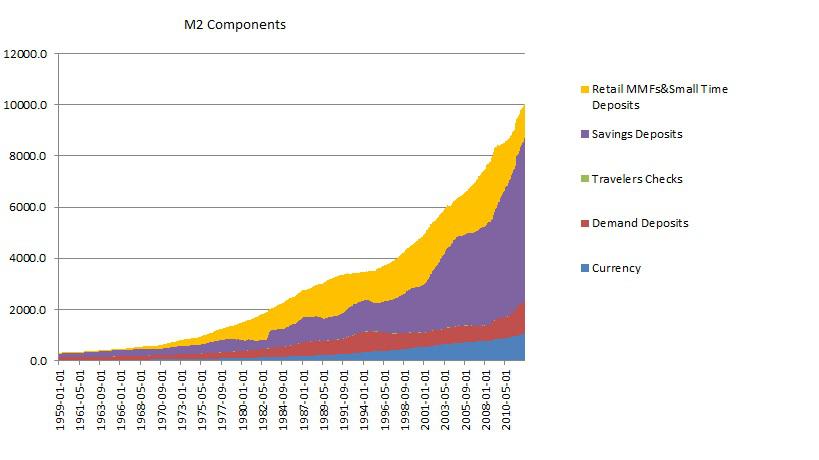

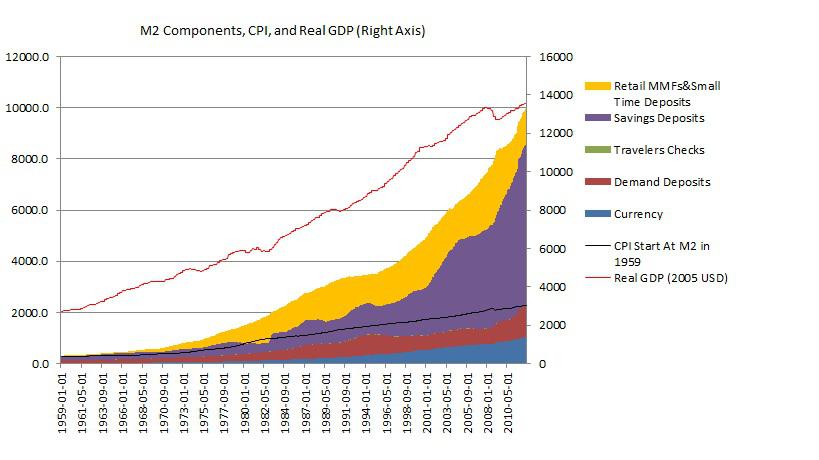

With these components, including currency and savings-type deposits, we have our most referenced statistic for money supply. Show below is a time series of M2 since 1959, broken down by component.

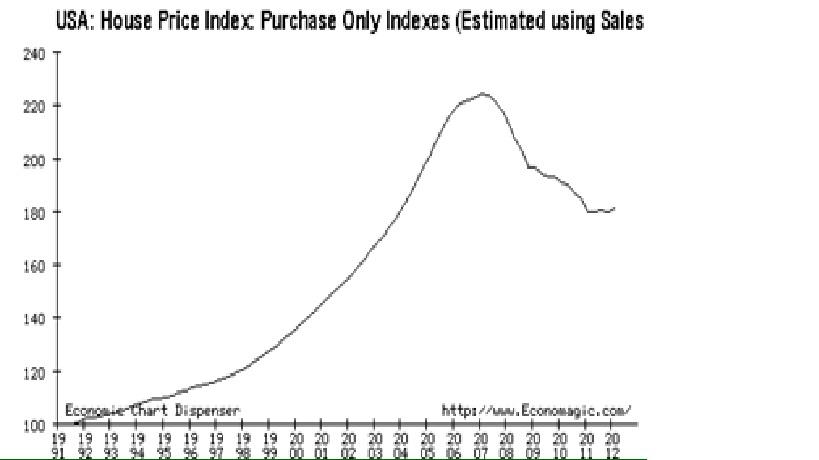

As you can see, M2 has steadily grown throughout the decades with fast growth periods in the early 2000s and currently. M2 and components will generally be most sensitive to bank behavior, not necessarily the Fed. The Fed influences bank behavior and market equilibrium to an extent with its participation in credit markets, but at the end of the day, M2 is more of a bank/consumer relationship than a reserve banking direct cause. With a combination of (1) higher lending, (2) higher savings, (3) higher international conversion to dollar accounts, or (4) liquidating illiquid assets, M2 and its components grow. If the Fed wants to influence or target M2 it can make policy decisions much like this recent announcement to encourage lending, equilibrium, and behavior. With the move targeted at the mortgage market, I expect this move, although liquidity-promoting, to potentially impact M2 less than some may expect because some savings funds could transition as down payments into the housing market. Looks like a fine buying opportunity in housing in many regional markets. FHFA National House Price Index shown below.

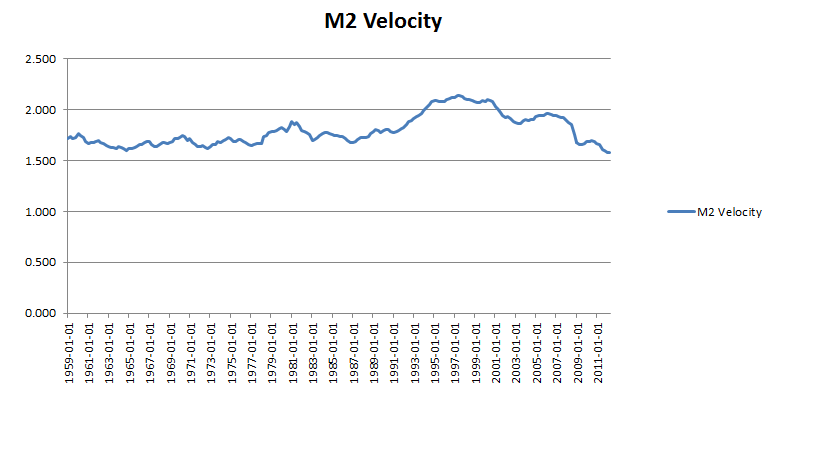

But the fact is, even pre-dating the announcement, July and August's M2 observations show that money supply is growing at a rather impressive rate. The relationship between monetary base growth and GDP is an interesting one, known as velocity. By definition MV2 is:

Velocity is a ratio of nominal GDP to a measure of the money supply. It can be thought of as the rate of turnover in the money supply--that is, the number of times one dollar is used to purchase final goods and services included in GDP.

Calculated velocity is measured directly through GDP and M2, and is increasing when the GDP per money base is increasing. As displayed in the chart below, M2 velocity has been dropping over the recent quarters and is at multi-decade lows.

The question remains: how do components of M2 impact this velocity measure? Is there some stealth "churn" in the banking system that allows different classes of deposits to impact velocity disproportionately?

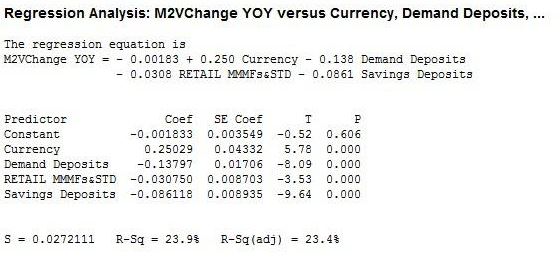

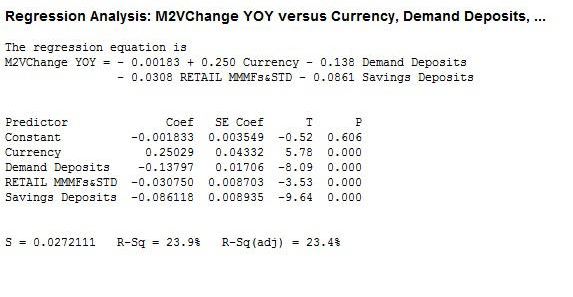

What the below regressions show, is that there is ONE relationship that has a positive impact on velocity. It is the amount of currency growth in the economy. This makes sense as this is the most readily accessible spending money for people. When we see currency's share of M2 increase year-over-year, we get a very solid predictor for MV2 change rates.

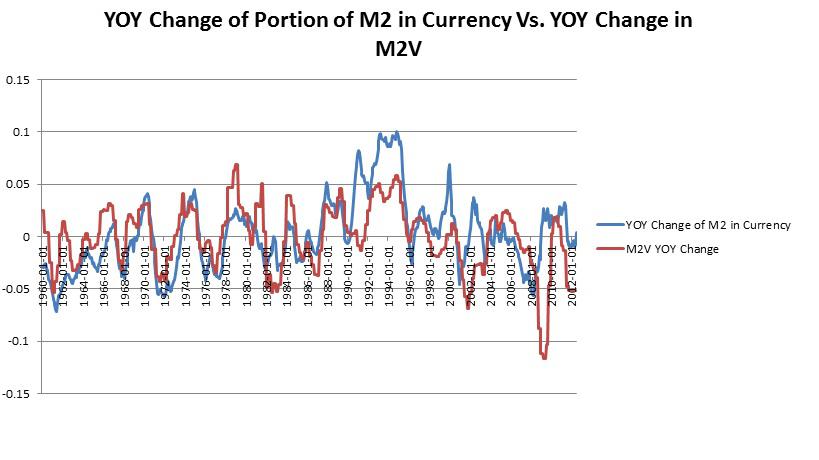

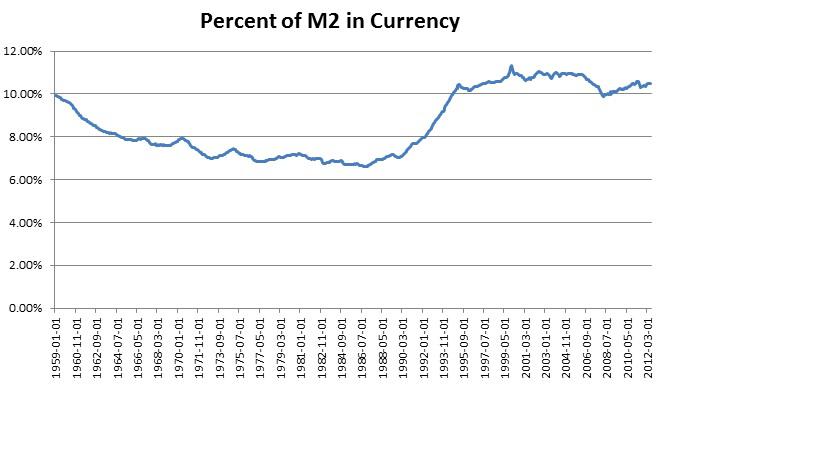

The statistician in me is compelled to explain how we get a better R^2 fit with the one-factor "Percent of M2 in Currency" model than the four-factor "Component by Component Model" (this is very unusual statistically, as more predictors should always give a tighter fit). Two answers: First, it shows that currency's impact on velocity is much more pronounced than any other M2 class. Second, there is no accounting for volume and relative volume of classes in the "component by component" model. Therefore the simplified statistic of "Percent of M2 in Currency" is actually a more dynamic data series, and expresses the only significant causal relationship for velocity more accurately throughout time. Visualizing the relationship:

Incidentally, as shown in the charts above, currency's share of M2 finally turned to positive YOY change in July, and is relatively high on an absolute level. This all on top of 8% year-over-year M2 growth. If these aren't signals to front-run a higher than expected 2012 Q3 nominal GDP, I am not sure what would be.

To be clear, I am not sure how much these monetary impacts are already priced into the market, but having bets on the side of nominal GDP would generally seem wise. There is also a matter of inflation that (if it ever shows up) would erode purchasing power and have an impact on balance sheets.

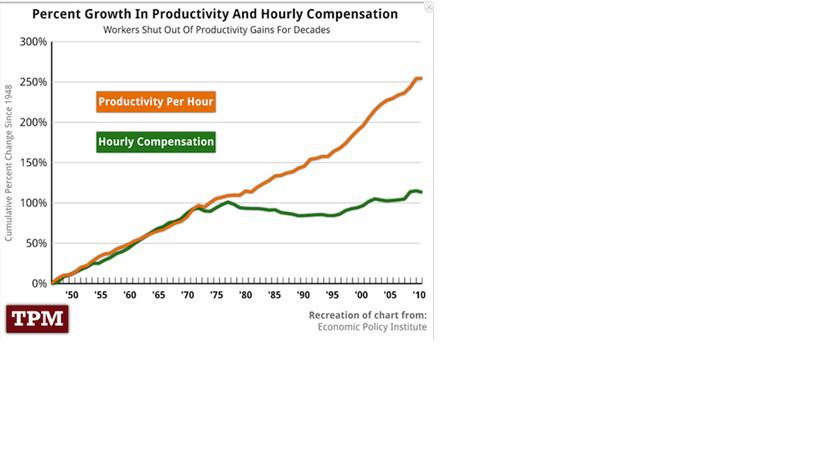

Which leads us to a question for monetarists: With money supply growing, why has not inflation responded? At risk of butchering the issue, I think price points may have something to do with it. Borrowing this chart from SA contributor ShareHolders Unite, we see the broken down relationship between productivity and compensation. While it does not directly show the distribution of wealth, you can infer the consequences looking at it together with corporate savings growth.

With purchasing power created, in either the form of M2 or credit, and not necessarily distributed to the vast majority of people, a business still needs to access

this

population as customers. So the business sets its price points to optimize profits, which can mean beneficially-low price increases for those who can afford to pay more, as the business wants to reach a full breadth of customers. It seems like, at least for now, inflation is dormant in part because of this wealth disparity. Even though I find it hard to believe that there will not be some sort of trickle down eventually, and despite distributions, consumer prices move higher.

When we plot money supply growth against inflation and real GDP, the chart is a bit troubling. M2 growth consistently outpacing inflation must highlight the wealth distribution effect. I don't have any other good answers for Milton Freidman on why M2 wouldn't impact it more directly (or as some may argue, at all).

Conclusion and Investment Implications

My approach to buying into this market is to be selective and to look for price paths that haven't reflected the big picture. With confidence that real and nominal GDP will be supportive to risk assets, at least in the short term, a variety of assets purchased in dollars would seem appealing. In terms of stocks, I favor metals [Stillwater Mining (SWC), North American Palladium (PAL), Allegheny Technologies Incorporated (ATI), Aluminum Corporation of China Ltd (ACH)], energy commodities [Arch Coal (NYSE:ACI), Peabody Energy (NYSE:BTU), Alpha Natural Resources (ANR) BP, Exxon Mobil (NYSE:XOM)] and real estate. It remains tough for me to fathom how some commodities priced in dollars being actively debased, haven't moved much to the upside. Bank stocks [Bank of America (NYSE:BAC), JP Morgan (NYSE:JPM) Wells Fargo (NYSE:WFC) Citi (NYSE:C)] that have a ton of collateral and lending exposure in real estate should also be a winner if and when housing prices increase, like I expect them to.

I would be underweight indebted consumer cyclical stocks which have borrowing cost vulnerable to movements in underlying interest rates and producer price inflation. The USD also would seem like a bad currency to hold for the low carry and the inflation risks. So long as the country's current account deficit remains negative, there is simply no convincing me that the dollar can move higher for a protracted period. Ideally, markets respond to the policy actions and the dollar can gradually move lower without any shocks, which will in turn, lower the cost of employment against international competition, and therefore the unemployment rate.

Disclosure: I am long ACI. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it. I have no business relationship with any company ...

more