If You Aren’t Confused By The Lack Of Mini-recessions, Then You Don’t Understand The Issue

It’s often said that if you think you understand quantum mechanics, then you don’t actually understand it. That may not be true of Eliezer Yudkowsky, Scott Aaronson and Robin Hanson, but it’s true of most average people. (Thankfully, I don’t even think I understand it.)

Whenever I discuss the lack of mini-recessions, commenters will offer explanations. One argument is that the highly diversified nature of the US economy leads to shocks in one sector being balanced out with growth in other sectors.

That might be in some way relevant to the issue (indeed I suspect it is.) But it’s certainly not an explanation. After all, we do have medium size recessions and large recessions. So this “explanation” actually explains far too much.

Think of it this way. Everyone should agree that some factor causes recessions in the US, on average once about every 5 years. Let’s call this factor X, or factors X, Y, and Z, if you think there are three primary causes. If big X shocks cause big recessions, and medium X shocks cause medium recessions, why don’t small X shocks cause small recessions?

Maybe there are no small X shocks. But why not? Everything we know about both the natural world and the human world suggests that small shocks are almost always more common than medium shocks, which are more common than big shocks. This is obviously true of things like earthquakes, but also true of human shocks like murders, traffic accidents, and wars. Single murders are more frequent than mass murders, single and two car accidents are more common than 10 car pile-ups. Small wars are more frequent than world wars.

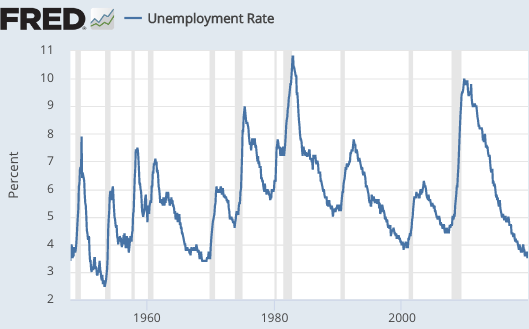

It is true that medium recessions are more frequent than big recessions. So why aren’t small recessions even more frequent? Indeed why don’t we have ANY mini-recessions, defined as unemployment rising by 1.0% to 2.0%, and then falling back.

My hunch is that it has something to do with interest rate targeting, procyclical monetary policy, and policy lags, but I can’t quite figure out exactly how. If the Fed shifts to level targeting and we start having mini-recessions, then that would confirm the role of monetary policy.

PS. The closest we’ve come is the 1959 steel strike when the unemployment rate rose by 0.8%, and immediately fell back again. Otherwise, a 0.6% rise is the largest increase short of a recession:

PPS. Off-topic, you really should be reading Slate Star Codex. Scott Alexander is not an economist, but his posts on economics are often better than 95% of the posts written by economists.