Why You Shouldn’t Borrow Too Much Money, China Edition

When the US housing bubble burst in 2007, most observers were focused on the threat to Wall Street banks and their massive derivatives books. This was a legitimate fear, since the worst-case scenarios involved the death of Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan Chase, with all the stock market carnage that that implied.

But for China the stakes were a lot higher — picture half a billion people taking to the streets and demanding an end to a government whose only claim to legitimacy was its ability to provide millions of ever-more-lucrative jobs.

So while the US was bailing out every bank in sight with lower interest rates and loan guarantees, China upped the ante by ordering pretty much every sector if its economy to start building things with borrowed money. The result was the biggest infrastructure binge in history, in which roads, bridges, airports, and — hey, why not — entire new cities sprang up in just a few years, providing jobs for millions of would-be rioters and a torrent of cash flow for foreign suppliers of iron ore, copper, cement, steel, lumber, and every other industrial commodity you can name.

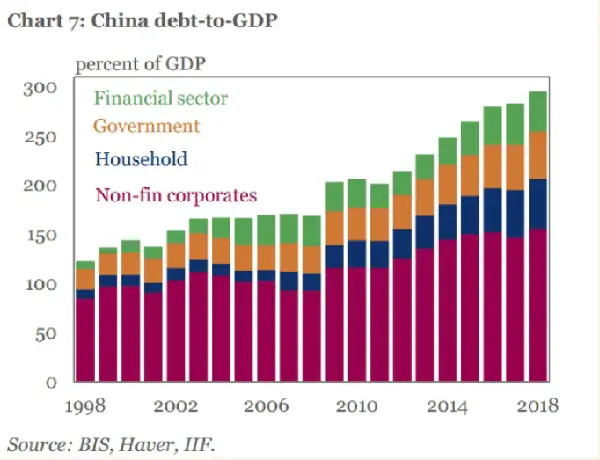

China boomed, the rest of the world recovered, and today’s longest-ever economic expansion was born. And Chinese debt-to-GDP soared to record-high levels.

Now dial back the perspective to that of a single hypothetical family. Say one of the breadwinners loses their job and the family’s income is cut in half. They can choose to scale back their spending to match their newly-diminished circumstances and accept the resulting turmoil of fewer cars, smaller house, public rather than private schools, etc. Or they can max out a series of credit cards and just go on as before, avoiding stress in the moment at the cost of bigger bills — and greater fragility — in the future.

The second strategy will work if the unemployed breadwinner gets a new job reasonably soon and — crucially — if no other crisis pops up that requires (now nonexistent) resources. No illness, no new job loss, no leaky roof, no wrecked car … and things might work out.

Now zoom back out to China, which chose strategy number two and is currently “rich” but also way too leveraged to handle another shock to the system. Just in time for a pandemic that shuts down half the country. From today’s South China Morning Post:

Forget Sars, the new coronavirus threatens a meltdown in China’s economy

Never before has China paid such an economic price for an epidemic as it has done already with the coronavirus, which originated in the Chinese city of Wuhan and causes the disease now officially known as Covid-19. And the damage is spreading.

It is obvious that the economic impact of Covid-19 will be far more severe than that of Sars, or any other previous epidemic.

Whole cities have been locked down, effectively grinding some local economies to a halt since Beijing declared all-out war on January 23. Currently, 30 of China’s 31 provinces have declared a top-level public health emergency, with all major cities and economic hubs effectively shut for weeks. The government has locked down 56 million people in quarantine in Hubei, banned tens of millions more from travelling across the nation, and imposed restrictions on activities in most urban areas. The Lunar New Year holiday has been extended for one or two weeks for most of the country. At the peak, provinces accounting for almost 69 per cent of China’s GDP were closed for business, according to Bloomberg Economics.

For the millions of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in China, the nightmare may be just beginning. Many small manufacturers fear foreign customers will shift orders to other countries due to disruptions in production and delivery. In a survey of 995 SMEs by academics from Tsinghua and Peking universities, 85 per cent said they would be unable to survive for more than three months under the current conditions. If the disruption goes on long enough, it could trigger a wave of bankruptcy among SMEs, which contribute more than 60 per cent of China’s GDP, 70 per cent of its patents and account for 80 per cent of jobs nationwide.

A financially solid country might be able to weather this kind of crisis by drawing down reserves and using its stellar credit to take on new, temporary debt. But an already over-leveraged system may not have those options.

As for what part of China’s economy blows up first, check out the repayment schedule of municipal debt. These are the cities and states that borrowed immense amounts of money — much of it in US dollars — to build the previously mentioned roads, bridges, etc. Much of this infrastructure was already failing to generate cash flow sufficient to cover the related debt. Now those cash flows are drying up.

China, in short, is providing a life lesson for the rest of us in how to respond to a crisis. Remember it next time you think about maxing out a credit card.